Received 3 March 2023; Revised 30 May 2023; Accepted 5 July 2023.

This is an open access paper under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode).

Daria Ilczuk, Ph.D. candidate, Doctoral School of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Gdansk, Wita Stwosza 63, 80-308 Gdansk, Poland, e-mail: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.  , corresponding author.

, corresponding author.

Łukasz Dopierała, Ph.D., Assistant Professor at the Department of International Business, Faculty of Economics, University of Gdansk, Armii Krajowej 119/121, 81-824 Sopot, Poland, e-mail: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Joanna Bednarz, Associate Professor, Head of the Department of International Business, Faculty of Economics, University of Gdansk, Armii Krajowej 119/121, 81-824 Sopot, Poland, e-mail: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Abstract

PURPOSE: Along with demographic changes, it is increasingly frequent that many mature people resign from their full-time jobs and decide to start their own businesses at a later age. Entrepreneurial activity among this group of so-called silver entrepreneurs can be caused by many motives, but these factors usually remain unknown to current employers or do not constitute a valid reason for understanding and keeping a mature person in the workplace. The purpose of this paper is to present new scientific results concerning entrepreneurial motivations, both internal and external, and the previous experiences of silver entrepreneurs from Eastern Europe based on an example from Poland. METHODOLOGY: We analyzed a unique sample of 1,003 owners of micro and small enterprises from Poland. The sample included only people over fifty. Our empirical study used a survey to explore the motivations and experiences of silver entrepreneurs that influenced their decision to start a business later in life. We linked attitude toward the behavior with motivation and utilized the “pull” and “push” factors. We utilized logistic regression to determine the factors related to starting a business above fifty. We also used the ordinary least square regression to determine the relationship between the explanatory variables and the age of starting a business by the respondents. FINDINGS: We found that the main “pull” factor positively influencing the start of business activity by silver entrepreneurs is the fulfillment of dreams as a broadly understood need for self-realization. However, the “push” factors (such as the occurrence of ageism in the workplace, as well as the loss of employment and lack of other opportunities on the labor market) significantly reduced the probability of starting a company at the age of over fifty. On the basis of the positive impact of a “pull” factor, it can be concluded that entrepreneurial activity at a later age is the result of opportunity-based entrepreneurship. Due to the negative impact of the job-loss factor, people made redundant started their business activity at an earlier age, before the age of fifty. Regarding external entrepreneurial motivations, the support received from family is the most important factor related to the individual’s environment affecting starting a business by silver entrepreneurs. However, the support from friends and the support from government bodies were not significant factors influencing starting a business at a later age.IMPLICATIONS: Findings from our study have implications for both employers and groups who support entrepreneurship. First, from the point of view of employers, the occurrence of ageism in the previous workplace could have resulted in resignation from full-time employment at an earlier age and a faster start of business activity. It is surprising that negative behavior towards older employees may also be associated with resignation from work by younger people. From the point of view of government bodies and other stakeholder groups related to the development of entrepreneurship, it is interesting that the support received from government bodies in conducting business activities was statistically insignificant for each group

of respondents. This suggests the need to identify effective support and to design a comprehensive strategy for the development of silver entrepreneurship. ORIGINALITY AND VALUE: The vast majority of previous studies used secondary data or focused mainly on Western Europe, in particular the United Kingdom, Finland, and France. Our contribution is to provide empirical evidence about the silver entrepreneurs from Eastern Europe, especially Poland. Our research included individuals who actually run their own businesses, opposite to previous studies that take into account people who are just considering starting a business. This is particularly important in relation to research on the entrepreneurial intentions of mature people to undertake entrepreneurial activities at a later age, and the real motivations of silver entrepreneurs.

Keywords: silver entrepreneurs, ageing, entrepreneurship, entrepreneurial motivations, push/pull factors

INTRODUCTION

The aging of society is one of Europe’s most important economic problems affecting the labor market. The issue of entrepreneurship among mature people expands the current discourse on reduced inequalities in relation to United Nation Sustainable Development Goal 10 in the age context (UN General Assembly, 2015). Mature people are a group at risk of exclusion from the labor market due to their age. Therefore examining the experience and motivation of silver entrepreneurs will contribute to strengthening the position of these people among society. In addition, supporting entrepreneurship is one of the tasks of Sustainable Development Goal 8, which is promoting stable, sustainable, and inclusive economic growth, full and productive employment, and decent work for all people (UN General Assembly, 2015).

Regarding the characteristics of entrepreneurs at a later age, researchers often focus on defining this concept and the terminology used, as well as identifying appropriate target age groups. In the literature, several terms of entrepreneurship among mature people can be found, such as older entrepreneur (Kautonen et al., 2008; Kautonen, Down, et al., 2013; Kerr & Armstrong-Stassen, 2011; Kibler et al., 2011, 2012, 2014; Maâlaoui et al., 2013; Wainwright & Kibler, 2013), elder entrepreneur (De Bruin & Firkin, 2001), senior entrepreneur (Efrat, 2008; Kautonen, 2013; Pilkova et al., 2014, 2016; Soto-Simeone & Kautonen, 2021), silver entrepreneur (Ahmad et al., 2014), grey (or gray) entrepreneur (Harms et al., 2014; Stirzaker et al., 2019), second-career entrepreneur (Baucus & Human, 1994), third age entrepreneurs (Botham & Graves, 2009; Kautonen, 2008, 2013; Lewis & Walker, 2013). Several authors also use short terms resulting from the combination of adjectives describing aging with the word entrepreneur, like elderpreneur (Patel & Gray, 2006), and seniorpreneur (Maâlaoui et al., 2013).

For consistency and lack of confusion, we will use the term silver entrepreneurship throughout this article to refer to mature people who decided to start their own business at a later age, following Ahmad et al. (2014). We also use the phrases entrepreneurship among mature people, entrepreneur at a later age, and we avoid terms such as senior entrepreneur or older entrepreneur due to the neutrality in describing a group of people at a later age and avoiding associations with a lack of vitality among this group. The word mature is intended to evaluate positively because, unlike words such as old, and senior, it does not refer to age, but emphasizes status and experience.

Previous research conducted on mature people has focused mainly on preventing this group’s exclusion from the labor market. However, along with demographic changes, it is increasingly frequent that many mature people resign from their full-time jobs and decide to start their own businesses, according to the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (Schott et al., 2017). Manifestations of individual entrepreneurship among this group can be caused by many motives, but these factors usually remain unknown to current employers or do not constitute a valid reason for understanding and keeping a mature person in the workplace.

The relatively limited literature in the field of silver entrepreneurship still does not provide exhaustive information on this important aspect, which is the motivations and experiences of these people, influencing the propensity to start a business. In addition, the results of previous empirical studies are often ambiguous. Moreover, the existing literature focuses mainly on Western Europe, in particular the United Kingdom (Soto-Simeone & Kautonen, 2021; Stirzaker & Galloway, 2017), Finland (Kautonen, 2008), France (Maâlaoui et al., 2013), and little concerns the countries of Eastern Europe, including Poland. The findings of Červený et al. (2016) show differences in the activity of silver entrepreneurship between Eastern and Western Europe and conclude that other research would be needed to understand how cultural and structural differences can influence the development of entrepreneurship among mature people. In addition, Kautonen et al. (2010) and Minola et al. (2016) emphasize that environmental issues at the regional and national levels can influence silver entrepreneurship. Therefore, future research will be particularly justified in Poland as a transition country, where mature people had to face the realities of an open market economy, significantly different from the centrally planned economy.

The main purpose of our article is to identify entrepreneurial motivations, both internal and external, which influenced the decision to start a business only at a later age. Our research also takes into account the previous experiences of mature people. In order to investigate the motivations and experiences of silver entrepreneurs that influenced their decision to start a business later in life, we used a combination of the push/pull approach (PPA) and the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB). To understand the reasons for the decision to start a business, the scientists used the PPA, dividing the factors influencing entrepreneurship activity into two categories (Kirkwood, 2009). In addition, the TPB has also found practical application in research focusing on entrepreneurial intentions and business creation, especially by mature people. Based on the theoretical background, we linked attitude toward the behavior (from the TPB) with motivation and utilized the “pull” and “push” factors from the PPA (Harms et al., 2014). We analyzed a unique sample of 1,003 owners of micro and small enterprises from Poland (only people over fifty were included). Based on the literature review, we observed that the vast majority of previous studies used secondary data (Biron & St-Jean, 2019). Therefore, our contribution is to provide empirical evidence about the entrepreneurial motivations and experiences of mature people from Eastern Europe, especially Poland. In addition, our research included individuals who actually run their own businesses, opposite to previous studies that take into account people who are just considering starting a business (Kautonen et al., 2010; Kautonen, van Gelderen, et al., 2013). This is particularly important in relation to research on the entrepreneurial intentions of mature people to undertake entrepreneurial activities at a later age, and the real motivations of silver entrepreneurs.

This paper is structured as follows. The second section presents the theoretical background, focusing on the concept of entrepreneurship among mature people, their internal entrepreneurial motivations, previous experiences, and external factors influencing entrepreneurial activities. The third section explains the process of data collection and analysis and the method used for the research. The fourth section discusses the results of the analyses. The last section presents a summary of the research and the debate on the conclusions from the research, as well as theoretical, practical, and managerial implications. It also identifies the study’s limitations and suggests some directions for further research.

LITERATURE REVIEW AND HYPOTHESES DEVELOPMENT

Concept of silver entrepreneurship

The key research topics and concepts related to silver entrepreneurship are mainly divided into three conceptual categories: the “who” category (which focuses on the characteristics of this group of entrepreneurs), the “why” category (examining the motivations which precede the intention to undertake entrepreneurial activities by mature people) and the “how” category (which analyzes the entrepreneurial process itself and the limitations faced by silver entrepreneurs) (Biron & St-Jean, 2019).

Kautonen has proposed definitions of silver entrepreneurship as individuals who become self-employed or start a new business late in their working career (Kautonen, 2008) and as individuals aged fifty or above who are planning to start a business, are currently in the process of starting one, or have recently started one (Kautonen, 2013). Blackburn et al. (2000) described silver entrepreneurship as mature entrepreneurs, especially those who have retired or opted for early retirement, to launch an entrepreneurship career.

The researchers mentioned that silver entrepreneurship is also identified as retirees (voluntary or involuntary) who started second-career businesses (Baucus & Human, 1994). At the same time, Bornard & de Chatillon (2016) stated that silver entrepreneurship refers to an individual who undertakes an entrepreneurial experience (creating or acquiring) as a second-career phase post the age of fifty. Other researchers, such as Maâlaoui et al. (2012), reported that silver entrepreneurship denotes individuals who have undertaken an entrepreneurial experience after the age of forty-five and wish to face social disengagement and extend their professional activities.

In previous studies, the authors more concisely described entrepreneurship among mature people, for example, an elderly person aged fifty or over who owns and operates a business (Patel & Gray, 2006), older individuals over fifty (Efrat, 2008), entrepreneurship or self-employment, fifty and over (De Bruin & Firkin, 2001), entrepreneurs who become self-employed at a mature age (Harms et al., 2014), an individual aged 55–64 who has created a business for the first time (Rossi, 2009). There is also an approach based on the typological categorization of entrepreneurs around retirement age (Maâlaoui et al., 2013; Singh & DeNoble, 2003; Wainwright et al., 2015).

Silver entrepreneurship has several definitions. However, the idea behind this concept is the same, which means individuals nearing retirement who launched a new business after a career as a salaried worker (Bornard & Fonrouge, 2012). The general difference between the various definitions relates primarily to the age at which the individual starts a business. Based on the literature review, we noticed that most of the authors focus on the group of people over fifty, but a few researchers have extended the group to people aged thirty and older or forty and older (Ahmad et al., 2014; Say & Patrickson, 2012).

Internal entrepreneurial motivations and previous experiences

Previous research on the phenomenon of silver entrepreneurship is characterized by interdisciplinarity, using combinations of dimensions such as the social, economic, and psychological. The multidimensional research approach is based on economic theories and psychosocial theories. For example, Maâlaoui et al. (2013) used theories of disengagement, activity, continuity, and socialization to explain and understand entrepreneurial intentions among people who have retired or are close to retirement.

When it comes to deliberations on the entrepreneurial intentions of mature people, scientists most often refer to the Model of the Entrepreneurial Event (SEE) (Shapero & Sokol, 1982) and the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) (Ajzen, 1991). For example, Stirzaker and Galloway (2017) used the SSE to investigate individuals over fifty from the United Kingdom who become entrepreneurs due to redundancy as the main reason to start a business. Elsewhere, Harms et al. (2014) applied the TPB to explore the drivers of motivations towards self-employment of silver entrepreneurs from the Rhine Valley with a particular focus on the organizational conditions at the previous employer.

In the literature, there are positive (“pull”) and negative (“push”) factors that refer to the opportunity or necessity to undertake entrepreneurial activities at a later age. “Pull” factors are related to self-realization, broadly understood as the need for achievement and the desire to fulfill a dream (Kautonen et al., 2010; Kautonen, van Gelderen, et al., 2013; Singh & DeNoble, 2003), the need for independence and work autonomy (Harms et al., 2014; Kautonen, 2008; Stirzaker et al., 2019), looking for new challenges (Gimmon et al., 2019; Singh & DeNoble, 2003; Stirzaker & Galloway, 2017), comparing the benefits of keeping a job or starting a business (Singh & DeNoble, 2003), the desire to increase income in order to realize specific dreams (Maâlaoui et al., 2013; Weber & Schaper, 2004), the search for the work–life balance including reducing working hours or having a more flexible work schedule (Harms et al., 2014; Kautonen, 2008; Stirzaker et al., 2019; Weber & Schaper, 2004), and willingness to remain active in retirement and integrate with the environment (Kautonen, 2008; Stirzaker et al., 2019; Weber & Schaper, 2004). In the light of findings from previous studies, we formulate the following research hypotheses regarding “pull” factors:

H1: In Poland, the possibility of more flexible working hours compared to

a full-time job has a positive impact on the probability of starting

a business after the age of fifty.

H2: In Poland, the willingness to seek new challenges in life has a positive

impact on the probability of starting a business after the age of fifty.

H3: In Poland, the fulfillment of dreams as self-realization has a positive

impact on the probability of starting a business after the age of fifty.

H4: In Poland, the willingness to be active and integrate with other people

has a positive impact on the probability of starting a business after the

age of fifty.

“Push” factors are related to the lack of prospects on the labor market or for permanent employment (Harms et al., 2014; Kautonen, 2008; Stirzaker & Galloway, 2017), dissatisfaction with the previous job (Harms et al., 2014; Stirzaker et al., 2019), providing adequate financial resources for everyday life (Harms et al., 2014; Maâlaoui et al., 2012; Stirzaker & Galloway, 2017), dismissal from work (Harms et al., 2014; Stirzaker & Galloway, 2017; Walker & Webster, 2007), and the issue of gender inequality, age discrimination, and technological exclusion of mature people in the workplace (Curran & Blackburn, 2001; Weber & Schaper, 2004). Researchers also mention other factors that may motivate individuals at a later age to start a business, such as using knowledge and professional experience from a previous job or holding managerial positions (Kautonen et al., 2010). Consequently, we verify the following research hypotheses regarding “push” factors:

H5: In Poland, the dissatisfaction with previous full-time employment has

a positive impact on the probability of starting a business after the age of fifty.

H6: In Poland, the occurrence of ageism in the workplace has a positive

impact on the probability of starting a business after the age of fifty.

H7: In Poland, the loss of employment and lack of other opportunities on the

labor market have a positive impact on the probability of starting

a business after the age of fifty.

In their typological categorization of silver entrepreneurs, Singh and DeNoble (2003) mentioned personal achievement and the fulfillment of dreams as factors motivating the silver entrepreneur who has entrepreneurial tendencies but never used them for various reasons. Stirzaker et al. (2019) found that the most frequently reported motivations of silver entrepreneurs in the United Kingdom to start a business were related to independence and autonomy in the form of a desire to be their own boss. However, Stirzaker and Galloway (2017) also confirmed that new challenges are not a significant factor for a mature person who has been made redundant from a previous job and started their own business or self-employment. Elsewhere, Harms et al. (2014) indicated that flexibility related to maintaining a work–life balance is important not only for women silver entrepreneurs. At the same time, Weber and Schaper (2004) emphasized that aging and staying active also depend on the role of society and supporting the entrepreneurial activities of mature people. On the other hand, Curran and Blackburn (2001) indicated ageism and a lower ability to use new technologies as the main reasons for the resignation of mature people from full-time work and going into self-employment. The findings of Walker and Webster (2007) show that the redundancy and lack of alternative employment were the greatest reason for silver entrepreneurs to start their businesses.

“Pull” and “push” factors derive from the basic theories of entrepreneurial motivation (Amit & Muller, 1995). To understand the reasons for the decision to start a business, the scientists used the push/pull approach (PPA), dividing the factors influencing entrepreneurship activity into two categories (Kirkwood, 2009). In addition, the TPB has also found practical application in research focusing on entrepreneurial intentions and business creation. According to the TPB, intentions are defined as indications of how hard persons are willing to try and how much effort they are planning to exert in order to perform the behavior (Ajzen, 1991). In addition, Ajzen (1991) stated that intentions and, ultimately, behavior are connected with specific antecedents. TPB proposes the following independent determinants of intentions: attitude toward the behavior refers to the negative or positive evaluation of a given behavior by an individual, subjective norm refers to the degree of social pressure to perform or not to perform that behavior, while perceived behavioral control (PBC) refers to the perceived ease or difficulty of performing the intended behavior.

Initially, Kautonen (2008) applied the PPA to investigate the motivations of silver entrepreneurs and TPB was also used in further studies (Kautonen et al., 2011). Harms et al. (2014) proposed a new approach to the research based on the elements of TPB, and linked attitude toward the behavior with motivation and used of the PPA. With references to the TPB, Brännback and Carsrud (2019) pointed out that PBC should not be equated with the concept of self-efficacy due to clear differences. The basic theories of entrepreneurial motivation also take into account risk appetite, which is not widely explored in the topic of silver entrepreneurship (Amit & Muller, 1995). Another important research issue in the area of silver entrepreneurship is the perception of age in the context of business activities (Tornikoski et al., 2012).

The results of previous empirical studies are often ambiguous. Moreover, they mainly concern highly developed countries. Thus, we contribute to the literature by verifying the research hypotheses regarding “pull” and “push” factors.

External factors influencing entrepreneurial activities

Apart from internal factors, the development of silver entrepreneurship is also influenced by many external factors related to the environment at various levels (macro, meso, micro) (Wach, 2015). Several studies indicate the importance of support from family and friends in decisions to start a business among mature people. Kautonen et al. (2011) investigated the relationship between the approach of family and friends in the context of subjective norms and the entrepreneurial intentions of mature people. Ahmad et al. (2014) explored the support from friends as an opportunity for silver entrepreneurs to be inspired by other successful people. Another factor that may affect the entrepreneurial behavior of this group may be some business background related to having an entrepreneur as a family member (Schröder et al., 2011). Brännback and Carsrud (2019) focused on the relationship between having a family business background and entrepreneurial intentions in the context of gender. An important issue indicated by Pilkova et al. (2014) is also the support of government bodies and other stakeholder groups related to the development of entrepreneurship. On this basis, we contribute to the literature by verifying the following research hypotheses regarding external factors influencing the entrepreneurial activities of mature people:

H8: In Poland, family support has a positive impact on the probability of

starting a business after the age of fifty.

H9: In Poland, friends support has a positive impact on the probability of

starting a business after the age of fifty.

H10: In Poland, state support has a positive impact on the probability of

starting a business after the age of fifty.

Additionally, in order to understand the causes of the phenomenon better, the research should take into account cultural differences and the context related to the regional and national environment. Pilkova et al. (2014) investigated the relationship between the entrepreneurial propensity of mature people and the national entrepreneurial context in European countries, and their results showed different levels of business involvement depending on the country. Entrepreneurship among mature people is more obvious in highly developed countries where there is a high standard of living and an open market economy, like Northern Europe and Luxembourg, but is less apparent in the former Eastern Bloc countries. It should be emphasized that starting their own business by people at a later age is not always a manifestation of opportunity-based entrepreneurship, but is often also the result of an unfavorable situation on the labor market, which will result in a necessity-based entrepreneurship (Stirzaker & Galloway, 2017). In addition, it was observed that the conducted research focuses mainly on the area of Western Europe, in particular the United Kingdom, Finland and France, and little concerns the countries of Eastern Europe, including Poland. The findings of Červený et al. (2016) show differences in the activity of silver entrepreneurship between Eastern and Western Europe, and the conclusions highlight that other research would be needed to understand how cultural and structural differences can influence the development of entrepreneurship among mature people.

At the same time, Kautonen et al. (2010) and Minola et al. (2016) emphasize that environmental issues at the regional and national levels can have a profound influence on silver entrepreneurship. In addition, Kautonen et al. (2011) claim that national culture impacts entrepreneurial intentions, and Weber and Schaper (2004) add that it also affects age norms. Therefore, future research will be particularly justified in Poland as a transition country, where mature people had to face the realities of an open market economy, significantly different from the centrally planned economy.

METHODOLOGY

Sample and data collection

Our empirical study used a specially designed survey to explore the motivations and experiences of silver entrepreneurs that influenced their decision to start a business later in life. Based on a theoretical background, we used a combination of the PPA and the TPB, which assumes three sets of antecedents related to intentions and ultimate behavior: attitude toward the behavior, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. Following Harms et al. (2014), we linked attitude toward the behavior with motivation and utilized the “pull” and “push” factors from the PPA. Based on the literature review, the survey questionnaire was prepared and consisted of the following thematic blocks: basic information on running a business (including industry, start date), previous experiences (professional experience from job), assessment of positive and negative factors of entrepreneurial intentions (referring to attitude linked with the PPA), assessment of the individual’s environment (referring to subjective norms from the TPB). The survey also included questions relating to perceived behavioral control and self-efficacy (referring to the differences indicated by Brännback and Carsrud (2019), as well as an assessment of age perception, technological exclusion, and risk appetite. The last block contained questions about such socio-demographic factors as: gender, marital status, education, place of residence, and income. Before starting the research, a pilot study was conducted on 20 respondents (entrepreneurs over the age of fifty) to check the adequacy and comprehensibility of the questionnaire.

The main survey was conducted by the research company MRC Consulting from 05 January to 25 February 2022. The pattern of selecting entrepreneurs for the sample was as follows. Enterprises were selected randomly from the REGON register. The REGON register is a collection of information on economic entities in Poland kept by the Central Statistical Office. Only active REGON numbers assigned to natural persons conducting business activity were considered. The research company contacted the owner of the selected enterprise by telephone. If contact was possible, a survey was carried out. If communication was impossible, another entrepreneur was randomly selected. The Computer-Assisted Telephone Interviewing technique (CATI) was used in the data collection. The first question was to filter respondents and concerned the respondent’s age. Only people over fifty were included for further study. As a result of repeating the procedure, a sample of 1,003 respondents was collected. The final sample covered only owners of micro and small enterprises. According to the Report on Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises in Poland (Skowrońska et al., 2022), micro and small enterprises account for 99.2% of all Polish enterprises, which is why we focused on this group.

Of the entrepreneurs surveyed, 95% were male. The age of the respondents ranged from 51 to 69 years. The average age of the respondent was 56 years. The research sample was dominated by married people (86%). Due to the level of education, the most numerous group were those with higher education (48%). Due to the industry, entrepreneurs dealing in wholesale and retail trade were the dominant group (31%). The share of respondents representing other groups of industries ranged from 2% to 10%. The average age of starting a business activity for the respondents in the research sample was 42 years. About 10% of the respondents (103 people) started running a business over the age of fifty and about 60% of the respondents (602 people) started running a business over the age of forty. The structure of the sample is presented in Table A1.

Variable measurement

The general characteristics of the variables used in the study are presented in Table 1. In relation to the main objective of the study, we calculated the age of starting a business by the respondents. For this purpose, we used information about the respondent’s age and how long they have been running the business. On this basis, we classified respondents as silver entrepreneurs. Following the literature review, we concluded that most of the authors include people who started a business after the age of fifty into the group of silver entrepreneurs (Efrat, 2008; Kautonen, 2013; Patel & Gray, 2006). Therefore, our primary dependent variable is a binary variable that takes the value 1 if the respondent started a business after the age of fifty, and value 0 otherwise. It should be noted that in this case, people who started running a business before the age of fifty were treated as a control group. However, since some authors, such as Ahmad et al. (2014) and Maâlaoui et al. (2013), define the border of silver entrepreneurs even earlier, we decided to additionally define a dependent binary variable, assuming the value of 1 if the respondent started running a business after the age of forty, and value 0 otherwise. In this case, people who started running a business before the age of forty were treated as a control group. In order to check the robustness of the obtained results, we also decided to use as a dependent variable the age of starting a business activity by the respondent.

To verify the research hypotheses, we used three groups of independent variables measured on a five-point Likert scale. Each independent variable corresponded to one question of the survey questionnaire (Table 1). We could not use several questions to measure individual factors, because a questionnaire prepared in this way would be too long, and we wanted to conduct the study on a large enough group of respondents.

The first group is related to the support received from the individual’s environment in starting a business. We considered family, friends, and state support to start the business by respondents in the study. Following Kautonen et al. (2010), we treated support from family and friends as a measure of subjective norms, which means the individual’s perceptions of these people’s opinions on the decision to start or not to start a business. According to Pilkova et al. (2014), we also took into account the support received from government bodies in conducting business activities.

Table 1. Characteristics of the research variables

|

Definition/survey question |

Responses categories |

Source |

|

|

Dependent variables |

|||

|

Starting 40+ |

Starting a business by the respondent after the age of 40. |

1 (if yes); 0 (otherwise) |

(Ahmad et al., 2014; Maâlaoui et al., 2013) |

|

Starting 50+ |

Starting a business by the respondent after the age of 50. |

1 (if yes); 0 (otherwise) |

(Efrat, 2008; Kautonen, 2013; Patel & Gray, 2006) |

|

Starting age |

Age of starting a business activity by the respondent. |

An integer between 21 and 60 |

- |

|

Independent variables |

|||

|

Family support |

My family encouraged me to start my own business. |

Five-point Likert scale, ranging from “strongly disagree (1)” to “strongly agree (5)” |

(Ajzen, 1991; Kautonen et al., 2010, 2011) |

|

Friends support |

My friends encouraged me to start my own business. |

(Ahmad et al., 2014; Ajzen, 1991; Kautonen et al., 2010, 2011) |

|

|

State support |

I have received sufficient support from public institutions in running my own business. |

(Pilkova et al., 2014) |

|

|

Flexibility |

Thanks to my own company, I wanted to set a more flexible schedule compared to full-time work. |

(Harms et al., 2014; Kautonen, 2008; Stirzaker et al., 2019; Weber & Schaper, 2004) |

|

|

Challenge |

I am constantly looking for new challenges, which is why I decided to run my own company. |

(Gimmon et al., 2019; Singh & DeNoble, 2003; Stirzaker & Galloway, 2017) |

|

|

Dream |

Starting my own business was a dream come true. |

(Kautonen et al., 2010; Kautonen, van Gelderen, et al., 2013; Singh & DeNoble, 2003) |

|

|

Staying active |

I wanted to be active and integrate with other people, and running my own business enables me to do so. |

(Kautonen, 2008; Stirzaker et al., 2019; Weber & Schaper, 2004) |

|

|

Job dissatisfaction |

My previous job did not meet my expectations, so I decided to start my own business. |

(Harms et al., 2014; Stirzaker et al., 2019) |

|

|

Ageism |

In my previous full-time job, I experienced unequal treatment of some employees due to their older age. |

(Curran & Blackburn, 2001; Weber & Schaper, 2004) |

|

|

Job loss |

I lost my previous full-time job and I had no other opportunities to earn money, so I started my own company. |

(Harms et al., 2014; Stirzaker & Galloway, 2017; Walker & Webster, 2007) |

|

|

Control variables |

|||

|

Family business background |

Does a member of your family own and operate a business? |

1 (if yes); 0 (if no) |

(Brännback & Carsrud, 2019; Schröder et al., 2011) |

|

Former manager |

Have you ever been in a managerial position in a full-time job? |

1 (if yes); 0 (if no) |

(Kautonen et al., 2010; Weber & Schaper, 2004) |

|

Uses experience |

In running the company, I use my previous professional experience from full-time work. |

Five-point Likert scale, ranging from “strongly disagree (1)” to “strongly agree (5)” |

(Kautonen et al., 2010; Weber & Schaper, 2004) |

|

Age perception |

If I had to assess my age, I feel much younger than I really am. |

(Curran & Blackburn, 2001; Tornikoski et al., 2012) |

|

|

Internet use |

I can use the Internet on my own and navigate its resources. |

(Colovic et al., 2019; Curran & Blackburn, 2001) |

|

|

Risk appetite |

It is best to go in business where others are afraid, because there are more opportunities there. |

(Amit & Muller, 1995; Weber & Schaper, 2004) |

|

|

PBC |

I knew the necessary practical details to start a firm. |

(Ajzen, 1991; Harms et al., 2014; Kautonen et al., 2011; Liñán & Chen, 2009) |

|

|

Self-efficacy |

I am able to overcome many challenges related to running my own business |

(Brännback & Carsrud, 2019; Chen et al., 2001) |

|

|

Gender |

Respondent’s gender |

1 (if man); 0 (otherwise) |

(Kautonen et al., 2010) |

|

Marital status |

Respondent’s marital status |

Single Married Informal relationship Divorced Widow/widower |

(Maâlaoui et al., 2013) |

|

Education |

Respondent’s education |

Primary Vocational Secondary Higher |

(Kautonen, 2008) |

|

Residence |

Respondent’s place of residence |

Village Town below 50,000 residents City from 50,000 up to 100,000 residents City over 100,000 up to 250,000 residents City over 250,000 residents |

(Lewis & Walker, 2013) |

|

Industry |

Respondent’s business industry |

Manufacturing activities Construction and renovation services Wholesale and retail trade Transportation services Medical services Beauty and fitness services Hotel, restaurant and catering services Automotive services Financial and insurance services, real estate trade Professional, scientific and educational services Other services Other industry |

(Harms et al., 2014) |

The second group of independent variables concerns the positive factors influencing the undertaking of economic activity. We took into consideration the “pull” factors such as: the possibility of more flexible working hours compared to a full-time job (Harms et al., 2014; Kautonen, 2008; Stirzaker et al., 2019; Weber & Schaper, 2004), the willingness to seek new challenges in life (Gimmon et al., 2019; Singh & DeNoble, 2003; Stirzaker & Galloway, 2017), the fulfillment of dreams as self-realization (Kautonen et al., 2010; Kautonen, van Gelderen, et al., 2013; Singh & DeNoble, 2003), and the importance of being active while aging and integrating with the environment (Kautonen, 2008; Stirzaker et al., 2019; Weber & Schaper, 2004).

The third group of independent variables concerns negative (“push”) factors, among which the following were distinguished: the dissatisfaction with previous full-time employment (Harms et al., 2014; Stirzaker et al., 2019), the occurrence of ageism in the workplace (Curran & Blackburn, 2001; Weber & Schaper, 2004), as well as the loss of employment and lack of other opportunities on the labor market (Harms et al., 2014; Stirzaker & Galloway, 2017; Walker & Webster, 2007).

Based on the literature, we added a set of control variables to our study. There is empirical evidence that a family business background has a significant impact on starting a business (Brännback & Carsrud, 2019; Schröder et al., 2011). For this reason, we decided to control this factor by introducing a binary variable with a value of 1 when a family member of the respondent operates their own business.

The research conducted so far also indicates that the competences and experience resulting from previous full-time employment may have an impact on starting a business at a later age (Kautonen et al., 2010; Weber & Schaper, 2004). In our study, we decided to control whether the respondents had previously held a managerial position in a full-time job and whether they used their previous professional experience in running the company. Research conducted by Curran and Blackburn (2001), and Tornikoski et al. (2012) also indicates that the perception of age may significantly influence people’s decisions about starting a business. For this reason, we included the appropriate control variable in the study. Technological exclusion and the ability to use digital technologies may also be important when starting a business (Colovic et al., 2019; Curran & Blackburn, 2001). For this reason, we included a proxy control variable based on self-assessment of Internet literacy in the study.

Additionally, we included in the questionnaire questions controlling such personality traits of the respondents as their risk appetite (Amit & Muller, 1995; Weber & Schaper, 2004), perceived behavioral control (PBC variable) (Ajzen, 1991; Harms et al., 2014; Kautonen et al., 2011; Liñán & Chen, 2009), and self-efficacy (Brännback & Carsrud, 2019; Chen et al., 2001). Each feature was measured by one item in the survey questionnaire and it is represented in the model by the corresponding control variable. Detailed questions asked to the respondents and their sources are presented in Table 1.

In the study, we also controlled the socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents, such as gender (Kautonen et al., 2010), marital status (Maâlaoui et al., 2013), education level (Kautonen, 2008), and place of residence (Lewis & Walker, 2013). Moreover, we controlled the industry in which the respondents conducts their business (Harms et al., 2014). For further analysis and modeling, categorical variables were transformed into quantitative variables by assigning the appropriate dummy binary variable to each category. Descriptive statistics of the variables are presented in Table A2 and correlations between quantitative variables are presented in Table A3.

Modeling strategy

We used two analytical tools in the study: logistic regression and ordinary least squares (OLS) regression.

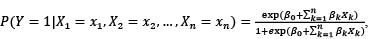

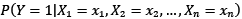

Firstly, we utilized logistic regression to determine the factors related to starting a business above the assumed age. Logistic regression is widely used in both current research on entrepreneurship (Al Mamari et al., 2022; Croitoru, 2020; Rodríguez-López & Souto, 2019) and research related directly to the effects of aging on entrepreneurial behavior (Le Loarne-Lemaire & Nguyen, 2019; von Bonsdorff et al., 2019). It allows for assessing the relationship between the explanatory variables and the probability of a certain event. In our study, the probability of starting a business after the age of fifty (Starting 50+ variable) and after forty (Starting 40+ variable) is considered. The logistic regression model we used is defined as:

represents the conditional probability of reaching the value of 1 by the dependent variable with specific values of the variables

represents the conditional probability of reaching the value of 1 by the dependent variable with specific values of the variables

represents the constant term,

represents the constant term,

is the k-th explanatory variable,

is the k-th explanatory variable,

represents the parameter for the k-th explanatory variable.

represents the parameter for the k-th explanatory variable.

We estimated the model parameters with the maximum likelihood method using Stata 13 software. Originally, we estimated the model including all available variables. The results for the initial models are presented in Table A4. The likelihood ratio chi-square test indicates that the models obtained for both the variables Starting 40+ and Starting 50+ are statistically significant. This means that at least some of the explanatory variables have a significant impact on the probability of starting a business after forty and fifty. The Hosmer-Lemeshow test indicated that there is no problem of poor fit of the model to empirical data. However, a detailed analysis of the parameter values and standard errors suggested the elimination of some insignificant variables. We applied a backwards stepwise regression procedure to improve the model specification. We set the significance level at 0.2 for removing variables from the model in all iterations because we wanted to keep every variable that might contribute some information. The results for the final models are presented in the next section.

We also used OLS regression to determine the relationship between the explanatory variables and the age of starting a business by the respondents. Robust standard errors were applied to the model because there was a problem of heteroscedasticity. The initial model included all the explanatory variables (Table A4). R2 indicated that the model fit to the empirical data is not high. However, we do not recognize it as a weakness of the method, because we treat the models as explanatory rather than predictive tools. After the backwards stepwise regression procedure, the insignificant variables were eliminated. There was no problem with collinearity in the final model. The variance inflation factor (VIF) ranged from 1.01 to 3.49. The mean VIF was 1.5. The results for the final OLS regression model are presented in the following section.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The estimation results of the final models are presented in Table 2. In the case of logistic regression, a statistically significant positive parameter value for a given explanatory variable indicates that it has a positive effect on the probability of the binary dependent variable taking the value 1.

Table 2. Final models

|

Variable |

Responses categories |

Dependent Variable |

|||||

|

Starting 40+ |

Starting 50+ |

Starting age |

|||||

|

Coef. |

Std. Err. |

Coef. |

Std. Err. |

Coef. |

Robust Std. Err. |

||

|

Family support |

0.264*** |

0.073 |

0.247** |

0.119 |

0.464** |

0.224 |

|

|

Friends support |

-0.234*** |

0.074 |

-0.402* |

0.214 |

|||

|

Flexibility |

0.518** |

0.263 |

|||||

|

Challenge |

0.136** |

0.066 |

0.164 |

0.104 |

0.340* |

0.191 |

|

|

Dream |

0.225** |

0.109 |

0.315 |

0.195 |

|||

|

Staying active |

0.170** |

0.071 |

-0.146 |

0.111 |

0.452** |

0.209 |

|

|

Job dissatisfaction |

0.193 |

0.122 |

0.297 |

0.205 |

|||

|

Ageism |

-0.216** |

0.090 |

-0.460*** |

0.145 |

-0.746*** |

0.271 |

|

|

Job loss |

-0.189** |

0.080 |

-0.338*** |

0.116 |

|||

|

Family business background |

0.780** |

0.347 |

|||||

|

Former manager |

-0.481** |

0.208 |

-1.490*** |

0.448 |

-1.298** |

0.548 |

|

|

Uses experience |

0.119* |

0.063 |

|||||

|

Age perception |

-0.157** |

0.065 |

-0.235** |

0.101 |

-0.370* |

0.202 |

|

|

Internet use |

0.320** |

0.146 |

|||||

|

Risk appetite |

-0.206* |

0.121 |

|||||

|

PBC |

0.180** |

0.072 |

0.498** |

0.224 |

|||

|

Self-efficacy |

0.190** |

0.076 |

0.716*** |

0.235 |

|||

|

Marital status |

Single |

Omitted |

Omitted |

||||

|

Married |

-0.480* |

0.290 |

0.754 |

0.502 |

|||

|

Informal relationship |

-0.892** |

0.427 |

1.421** |

0.672 |

|||

|

Divorced |

Reference category |

Reference category |

Reference category |

||||

|

Widow/widower |

0.501 |

0.747 |

Omitted |

- |

- |

||

|

Education |

Primary |

Omitted |

-0.428 |

0.792 |

|||

|

Vocational |

0.552** |

0.218 |

1.199** |

0.587 |

|||

|

Secondary |

0.118 |

0.160 |

-0.563 |

0.494 |

|||

|

Higher |

Reference category |

Reference category |

Reference category |

||||

|

Residence |

Village |

0.835 |

0.692 |

Omitted |

0.800 |

2.154 |

|

|

Town below 50,000 residents |

0.846*** |

0.259 |

1.474*** |

0.384 |

3.307*** |

0.713 |

|

|

City from 50,000 up to 100,000 residents |

-0.333 |

0.216 |

0.357 |

0.376 |

0.213 |

0.678 |

|

|

City over 100,000 up to 250,000 residents |

-0.105 |

0.207 |

0.280 |

0.381 |

0.989 |

0.624 |

|

|

City over 250,000 residents |

Reference category |

Reference category |

Reference category |

||||

|

Industry |

Manufacturing activities |

Reference category |

Reference category |

Reference category |

|||

|

Construction and renovation services |

0.053 |

0.362 |

0.656 |

0.636 |

1.446 |

1.064 |

|

|

Wholesale and retail trade |

0.286 |

0.273 |

0.563 |

0.495 |

0.748 |

0.800 |

|

|

Transportation services |

0.236 |

0.332 |

0.309 |

0.578 |

0.298 |

0.882 |

|

|

Medical services |

1.087*** |

0.340 |

0.874 |

0.578 |

2.805*** |

0.919 |

|

|

Beauty and fitness services |

0.132 |

0.370 |

1.705*** |

0.579 |

1.199 |

1.219 |

|

|

Hotel, restaurant and catering services |

1.696*** |

0.373 |

0.812 |

0.625 |

3.741*** |

0.854 |

|

|

Automotive services |

0.787** |

0.362 |

0.640 |

0.613 |

2.321** |

0.951 |

|

|

Financial and insurance services, real estate trade |

-0.646 |

0.538 |

0.819 |

0.754 |

0.393 |

1.478 |

|

|

Professional, scientific and educational services |

-0.038 |

0.393 |

0.997 |

0.623 |

0.254 |

1.260 |

|

|

Other services |

-0.110 |

0.599 |

1.211 |

0.829 |

-2.269 |

2.548 |

|

|

Other industry |

0.578 |

0.498 |

0.239 |

0.903 |

0.222 |

1.609 |

|

|

Constant |

-2.049** |

0.927 |

-3.022*** |

1.652 |

32.925*** |

2.291 |

|

|

Model fit |

|||||||

|

Number of obs. |

997 |

971 |

1003 |

||||

|

LR chi2 p-value |

0.000 |

0.000 |

|||||

|

Log likelihood |

-599.53 |

-287.45 |

|||||

|

Pseudo R2 |

0.108 |

0.121 |

|||||

|

R2 |

0.114 |

||||||

|

Hosmer-Lemeshow chi2 p-value |

0.576 |

0.422 |

|||||

Note: This table presents the logistic regression results for the Starting 40+ and Starting 50+ dependent variables, and the OLS regression of the Starting age dependent variable. Some categories of qualitative variables were omitted due to a small number of observations. Robust standard errors were used in the OLS estimation. ***, **, and * indicate statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively.

Based on the presented model, we verified the research hypotheses regarding push and pull factors as well as external factors (Table 3). The analysis of the variables representing the motivations to start a business indicates that the factor positively influencing starting a business after age fifty was the desire to fulfill the individual’s dreams, which represents an internal factor related to self-realization (H3). These results are partly consistent with the study by Kautonen et al. (2010), who treat self-realization as an element of the entrepreneurial attitude. Ahmad et al. (2014) pointed out that the possibility of self-achievement was a more important pull factor of entrepreneurial activities for mature people than the desire to increase income. The Flexibility (H1), Challenge (H2), and Staying active (H4) variables were statistically insignificant in the case of people starting a business after the age of fifty. The Flexibility variables were also statistically insignificant for both the Starting 40+ and the Starting 50+ dependent variables. This contradicts the results of Harms et al. (2014), where flexibility and work–life balance in general were the main positive factors for starting a business at a later age. The logistic regression analysis for the Starting 40+ dependent variable indicates that for people starting a business after the age of forty, looking for new challenges and staying active were significant factors. The above results are consistent with the conclusions of Stirzaker et al. (2019) that mature people prefer to invest their time in goals that are valuable to them compared to younger people who are looking for new challenges and integration with the environment.

The parameters of the push factors had the same signs for both the Starting 40+ and the Starting 50+ dependent variables. However, some push factors (the Ageism (H6) and Job loss (H7) variables) significantly reduced the probability of starting a business after the age of fifty. This means that people made redundant started their business activity earlier. This contradicts the findings of Stirzaker and Galloway (2017), indicating that another important negative factor after losing a job was the lack of alternatives, which was a result of necessity-based entrepreneurship. Harms et al. (2014) also mentioned that long-term unemployment is one of the main push factors of silver entrepreneurship. Redundancy may be related to starting a business at a younger age in the conditions of the economic crisis associated with the economic transformation in Poland and the lack of prospects on the labor market. Červený et al. (2016) investigated the entrepreneurial propensity of both the general population and mature people, comparing Western and Eastern Europe, and concluded that regardless of the group, Western European countries have a higher tendency to business initiatives, perhaps due to the historical background in the Eastern European countries. This is also in line with Kautonen (2008) and Pilkova et al. (2014), who have noted the importance of the national context in research, especially in relation to silver entrepreneurship.

Moreover, the negative value of the parameter for the Ageism variable suggests that the occurrence of this phenomenon in the previous workplace could have resulted in resignation from full-time employment at an earlier age and a faster start of business activity by the respondents, which is partially consistent with the assumptions of Curran and Blackburn (2001) and Weber and Schaper, (2004). This is an interesting result from the point of view of employers, as it suggests that negative behavior towards older employees may also be associated with resignation from work by younger people. On the other hand, we did not observe the influence of the factor of dissatisfaction with the previous full-time job (H5) on starting a business after the age of fifty. This is in contrast to the results obtained by Harms et al. (2014), where job dissatisfaction was caused by the high ambitions of silver entrepreneurs. Stirzaker et al. (2019) also listed this factor as significant, but job dissatisfaction was caused by the lack of freedom.

Variables representing external factors indicate that family support (H8) had a positive impact on the probability of starting a business after the age of fifty as well as after the age of forty. On the other hand, the support of friends (H9) had a negative impact on the probability of starting a business over the age of forty. This suggests that the support of friends can be an important motivator for people starting a business at a young age. Our results are in line with the research of Stirzaker et al. (2019), which emphasized that with increasing age, mature individuals prefer to spend more time and strengthen bonds with family members, especially with a partner, compared to younger people who are looking for new relationships and friends. Moreover, Harms et al. (2014) found that family members who also run their own business support more the entrepreneurial activities of mature people and that the influence of the family does not discourage individuals from starting a business at a late age, but the opinion of the closest family members may have a significant impact on the choice of the company’s industry. Kautonen et al. (2010) assume that the lack of support from the family has a negative impact on starting a business by mature people in the manual labor industry. The State support (H10) variable was statistically insignificant for each of the dependent variables, which is in line with the research of Pilkova et al. (2014).

Table 3. Verification of hypotheses

|

Hypotheses |

Supported/Unsupported |

|

„Push” factors |

|

|

H1: In Poland, the possibility of more flexible working hours compared to a full-time job has a positive impact on the probability of starting a business after the age of fifty. |

Unsupported |

|

H2: In Poland, the willingness to seek new challenges in life has a positive impact on the probability of starting a business after the age of fifty. |

Unsupported |

|

H3: In Poland, the fulfillment of dreams as self-realization has a positive impact on the probability of starting a business after the age of fifty. |

Supported |

|

H4: In Poland, the willingness to be active and integrate with other people has a positive impact on the probability of starting a business after the age of fifty. |

Unsupported |

|

„Push” factors |

|

|

H5: In Poland, the dissatisfaction with previous full-time employment has a positive impact on the probability of starting a business after the age of fifty. |

Unsupported |

|

H6: In Poland, the occurrence of ageism in the workplace has a positive impact on the probability of starting a business after the age of fifty. |

Unsupported |

|

H7: In Poland, the loss of employment and lack of other opportunities on the labor market have a positive impact on the probability of starting a business after the age of fifty. |

Unsupported |

|

External factors |

|

|

H8: In Poland, family support has a positive impact on the probability of starting a business after the age of fifty. |

Supported |

|

H9: In Poland, friends support has a positive impact on the probability of starting a business after the age of fifty. |

Unsupported |

|

H10: In Poland, state support has a positive impact on the probability of starting a business after the age of fifty. |

Unsupported |

Interesting insights can also be drawn from the control variables. The probability of starting a business after the age of fifty increased if the respondent had family members already running a business. The results of Harms et al. (2014) also indicated that being surrounded by family members who own companies better prepares a mature individual to start their business at a later age. This is also in line with the expectations of Brännback and Carsrud (2019), who assume that working in a family business has a positive impact on entrepreneurial intentions, especially in mature males. Having experience in a managerial position was associated with starting a business at an earlier age, which is inconsistent with the assumptions of Weber and Schaper (2004) that a greater level of management experience may provide silver entrepreneurs an advantage over younger entrepreneurs. In addition, the Age perception variable was negatively associated with the likelihood of starting a business at a later age. However, this parameter should be interpreted with caution. It suggests that people who started their own business earlier feel younger than their age. Kautonen et al. (2015) pointed out that mature people who positively perceive their psychological age, which means that they feel younger, more often show entrepreneurial intentions.

We also observed a positive relationship between the Internet use, PBC, and Self-efficacy variables and the probability of starting a business over the age of forty. However, this relationship was no longer present in the model for the Starting 50+ dependent variable. This suggests that people starting a business between the ages of forty and fifty had a lower sense of technological exclusion, as well as a higher sense of perceived behavioral control and self-efficacy. Our results are in line with research by Colovic et al. (2019), who found silver entrepreneurs to be less innovative than younger entrepreneurs, which may be due to cognitive decline with age and the ability to adopt new technologies. Curran and Blackburn (2001) also pointed out that mature people often have less ability to deal with new technology. However, since we used a proxy control variable, represented in the survey questionnaire by only one item, we believe that far-reaching conclusions should not be drawn in this case.

Taking into account the socio-demographic factors, it is worth pointing out that the probability of starting a business over the age of fifty and over the age of forty depended on the respondent’s place of residence. In turn, education had an impact on the likelihood of starting a business over the age of forty. However, Kautonen (2008) indicated that educational background also has an important influence on people starting a business at the age of fifty and over. Moreover, our results suggest that the respondent’s marital status significantly influences the probability of starting a business at an age above fifty, as pointed out also by Maâlaoui et al. (2013), adding other issues related to family status, such as financially dependent children at home.

The OLS regression results are generally consistent with the logistic regression results (Table 2, dependent variable: Starting age). The only difference appears in the impact of the Flexibility variable on the age of starting a business. The OLS regression indicates that the factors of working hours’ flexibility were associated with starting a business at a later age. However, we treat this result as ambiguous, as the results of logistic regression do not confirm this relationship. The OLS regression confirmed that the search for new challenges was associated with starting a business later in life, but not necessarily after the age of fifty. A similar relationship was found for the Staying active variable. The OLS regression also validated that the occurrence of ageism in the previous workplace could influence starting a business at an earlier age. Moreover, the OLS regression indicated that family support is associated with starting a business later in life, while friends support is associated with starting a business at an earlier age. The previously observed relationship that managerial experience is associated with starting a business at an earlier age was also confirmed. The analysis of control variables related to education level, place of residence, and industry also validated the relationships previously observed using logistic regression.

CONCLUSIONS

Silver entrepreneurship concerns professionally active people who still have some time left until retirement. They are usually characterized by considerable professional experience and they are looking for opportunities for the so-called late-career alternative. In addition, these people are also distinguished by the lifestyle that is specific to the roles and responsibilities at a mature age. In the article we concentrated on entrepreneurial motivations, external and internal, which influenced the decision to start their own business by mature people at a later age. We also took into account the previous experiences of silver entrepreneurs.

We found that the main “pull” factor positively influencing the start of business activity by silver entrepreneurs is the fulfillment of dreams as a broadly understood need for self-realization. Other “pull” factors included in our study, such as the possibility of more flexible working hours compared to a full-time job, the willingness to seek new challenges in life, and the importance of being active while aging and integrating with the environment, were not significant for people starting a business after the age of fifty. The “push” factor related to dissatisfaction with a previous full-time job was statistically insignificant for silver entrepreneurs. However, the “push” factors, such as the occurrence of ageism in the workplace, as well as the loss of employment and lack of other opportunities on the labor market, reduced the probability of starting a business at the age of over fifty.

On the basis of the positive impact of a “pull” factor, it can be concluded that in Poland the entrepreneurial activity of mature people at a later age is the result of opportunity-based entrepreneurship. Due to the negative impact of the job-loss factor, people made redundant started their business activity at an earlier age, before the age of fifty. This may be related to entering the business at a younger age in the conditions of the economic crisis associated with the transformation in Poland and the lack of prospects on the labor market.

When it comes to external entrepreneurial motivations, in our study the support from family was the main factor positively influencing the probability of starting a business after the age of fifty. However, the support from friends and the support from government bodies were not significant factors for silver entrepreneurs in our study. In addition, the only factor related to the previous experiences of mature people that had a positive impact on the likelihood of starting a business after the age of fifty was a family business background. Moreover, our results suggest that the respondent’s marital status significantly influences the probability of starting a business at an age above fifty. Based on our results, it can be concluded that the support received from family is the most important factors related to the individual’s environment in starting a business by silver entrepreneurs in Poland. Mature people respect the opinion of their family on the decision to start or not to start a business at a later age.

Other previous experiences of mature people included in our study, such as the using of competences and professional experience from previous full-time employment, was not significant for people starting a business after the age of fifty, as well as holding a managerial position was associated with starting a business at a younger age. Moreover, the perception of age was negatively associated with the likelihood of starting a business at a later age. It suggests that people who started their own business earlier feel younger than their age. No significant relationship was observed between technological exclusion, perceived behavioral control, and self-efficacy in the group of mature people starting a business after fifty. However, other results suggest that people starting a business between the ages of forty and fifty had a lower sense of technological exclusion, as well as a higher sense of perceived behavioral control and self-efficacy.

Our research has implications for both theory and practice. In terms of theoretical implications, our findings suggest that the entrepreneurial motivations identified by previous authors for mature people who engage in business activity at a later age may vary depending on the countries or regions under investigation. This implies the need for further research on cross-cultural differences. Comparing results from different countries or regions can provide valuable insights into the influence of culture, social norms, and support systems on the decision to start running a business at a later age. Furthermore, our research highlights the need for further examination of the psychological aspects related to entrepreneurship activity among mature individuals.

Findings from our study have practical implications for both employers and groups who support entrepreneurship. First, from the point of view of employers, the occurrence of ageism in the previous workplace could have resulted in resignation from full-time employment at an earlier age and a faster start of business activity. It suggests that negative behavior towards older employees may also be associated with resignation from work by younger people. From the government bodies and other stakeholder groups related to the development of entrepreneurship, it is surprising that the support received from government bodies in conducting business activities was statistically insignificant for each group of respondents. This suggests the need to identify effective support and to design a comprehensive strategy for the development of silver entrepreneurship in Poland, which is also important from the perspective of United Nation Sustainable Development Goals (UN General Assembly, 2015). Examples of support tools can include creating support networks for silver entrepreneurs. Organizing meetings, conferences, workshops, and mentoring programs can help build a community, facilitate the exchange of knowledge, and foster beneficial business relationships. An interesting approach could also involve supporting intergenerational entrepreneurship, where mature individuals collaborate with younger entrepreneurs. In addition, governments can implement administrative facilitations and training programs to promote entrepreneurial development among mature age groups. Searching for effective tools to support silver entrepreneurship could be also an interesting direction for further research.

There is a wide range of possibilities for other future research on the topic discussed in this paper. Therefore, we strongly encourage other researchers to follow and develop the research area, in particular the entrepreneurial motivations, both internal and external, of mature people to start doing business only at a later age, especially in other Eastern European countries. Another important issue for future research is the characteristics of business activities conducted by silver entrepreneurs, including the choice of industry, employment level, propensity to develop the company in the future, or the implementation of innovations. An interesting topic of research is also the impact of early retirement on starting a business at a later age in the case of privileged professional groups (in Poland, it concerns people working as, for example, soldiers, policemen, firemen, miners).

This study has some limitations. The main limitation is the proportion of women and men among the respondents. According to the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor Poland (Tarnawa et al., 2020), the group of silver entrepreneurs in Poland is dominated by men. We are aware that in our study the gender ratio is distorted and there is an overrepresentation of men. An additional limitation of the research is the specificity of entrepreneurs as a group of respondents. Entrepreneurs are characterized by a limited amount of time, which is related to a lack of willingness to take part in long surveys. Therefore, the questionnaire could not be too extensive and contain several questions on a given issue, which also imposed the selection of appropriate research methods used in the article. It should also be noted that the study may cover mature people who declare themselves as entrepreneurs, but who, in fact, are full-time employees who are self-employed only to settle accounts with their current employer. Therefore, further research may consider these limitations.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the editor and anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and suggestions. This article was supported by the University of Gdansk, Poland (Grant 533-0C10-GS035-22).

References

Ahmad, N. H., Nasurdin, A. M., Halim, H. A., & Taghizadeh, S. K. (2014). The pursuit of entrepreneurial initiatives at the “Silver” age: From the lens of Malaysian silver entrepreneurs. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 129, 305–313. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SBSPRO.2014.03.681

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

Al Mamari, F., Mondal, S., Al Shukaili, A., & Kassim, N. M. (2022). Effect of self-perceived cognitive factors on entrepreneurship development activities: An empirical study from Oman global entrepreneurship monitor survey. Journal of Public Affairs, 22(2), e2363. https://doi.org/10.1002/PA.2363

Amit, R., & Muller, E. (1995). “Push” and “pull” entrepreneurship. Journal of Small Business Management, 12(4), 64–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/08276331.1995.10600505

Baucus, D. A., & Human, S. E. (1994). Second-career entrepreneurs: A multiple case study analysis of entrepreneurial processes and antecedent variables. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 19(2), 41–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/104225879501900204

Biron, D., & St-Jean, É. (2019). A scoping study of entrepreneurship among seniors: Overview of the literature and avenues for future research. Handbook of Research on Elderly Entrepreneurship, 17–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-13334-4_2

Blackburn, R., Hart, M., & O’reilly, M. (2000). Entrepreneurship in the third age: New dawn or misplaced expectations? In 23rd ISBA National Small Firms Policy and Research Conference, 1–17.

Bornard, F., & de Chatillon, E. A. (2016). Il est toujours temps d’entreprendre. RIMHE: Revue Interdisciplinaire Management, Homme & Entreprise, 22(3), 44–66. https://doi.org/10.3917/RIMHE.022.0044

Bornard, F., & Fonrouge, C. (2012). Handicap à la nouveauté et seniors: l’entreprise créée par un senior bénéficie-t-elle de son expérience organisationnelle ? Revue Française de Gestion, 38(227), 111–125. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2204276

Botham, R., & Graves, A. (2009). The grey economy: How third age entrepreneurs are contributing to growth. NESTA Research Report, August, 1–83.

Brännback, M., & Carsrud, A. L. (2019). Context, cognitive functioning, and entrepreneurial intentions in the elderly. Handbook of Research on Elderly Entrepreneurship, 43–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-13334-4_3

Červený, J., Pilková, A., & Rehák, J. (2016). Senior entrepreneurship in European context: Key determinants of entrepreneurial activity. Ekonomicky Casopis, 64(2), 99–117.

Chen, G., Gully, S. M., & Eden, D. (2001). Validation of a new general self-efficacy scale. Organizational Research Methods, 4(1), 62–83. https://doi.org/10.1177/109442810141004

Colovic, A., Lamotte, O., & Bayon, M. C. (2019). Technology adoption and product innovation by third-age entrepreneurs: Evidence from GEM data. In Handbook of Research on Elderly Entrepreneurship (pp. 111–124). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-13334-4_7

Croitoru, A. (2020). Great expectations: A regional study of entrepreneurship among Romanian return migrants. 10(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244020921149

Curran, J., & Blackburn, R. A. (2001). Older people and the enterprise society: Age and self-employment propensities. Work, Employment and Society, 15(4), 889–902. https://doi.org/10.1177/095001701400438279/ASSET/095001701400438279.FP.PNG_V03

De Bruin, A., & Firkin, P. (2001). Self-employment of the older worker. Labour Market Dynamics Research Programme, 4, 1–21.

Efrat, R. (2008). Senior entrepreneurs in bankruptcy. Creigton Law Review, 42(1), 83–121.

Gimmon, E., Yitshaki, R., & Hantman, S. (2019). How to foster older adults entrepreneurial motivation: The Israeli case. In Handbook of Research on Elderly Entrepreneurship (pp. 211–226). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-13334-4_13

Harms, R., Luck, F., Kraus, S., & Walsh, S. (2014). On the motivational drivers of gray entrepreneurship: An exploratory study. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 89, 358–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2014.08.001

Kautonen, T. (2008). Understanding the older entrepreneur: Comparing third age and prime age entrepreneurs in Finland. International Journal of Business Science and Applied Management, 3(3), 3-13.

Kautonen, T. (2013). Senior entrepreneurship. A background paper for the OECD Centre for Entrepreneurship, SMEs and Local Development. University of Turku, LEED.

Kautonen, T., Down, S., & Minniti, M. (2013). Ageing and entrepreneurial preferences. Small Business Economics, 42(3), 579–594. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-013-9489-5

Kautonen, T., Down, S., & South, L. (2008). Enterprise support for older entrepreneurs: The case of PRIME in the UK. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour and Research, 14(2), 85–101. https://doi.org/10.1108/13552550810863071