Received 11 February 2020; Revised 2June 2020, 13 September 2020, 10 December 2020; Accepted 15 December 2020.

This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode).

Duong Cong Doanh, Ph.D., Researcher/Lecturer, Institution/Organization: National Economics University, Vietnam, Room 1008, 10th floor, A1 building, National Economics University, 207 Giai Phong Street, Hai Ba Trung, Hanoi, Vietnam, e-mail: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Abstract

Purpose: This study investigates the moderating role of self-efficacy on the cognitive process of entrepreneurship among Vietnamese students. Specifically, this study explores the moderating effects of entrepreneurial self-efficacy on the relationships between attitude towards entrepreneurship, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, and intention to become entrepreneurs. Methodology: By adapting the theory of planned behavior and using data collected from 2218 students in Vietnam, the author utilizes a meta-analytic path analysis in order to show that entrepreneurial intention is strongly influenced by attitude towards entrepreneurship, followed by self-efficacy and perceived behavioral control. Particularly, structural equation modeling (SEM) was employed to test the model fit and hypothesis. Findings: The study indicates that subjective norms have both direct and indirect effects on entrepreneurship intention. Moreover, although the moderating impacts of self-efficacy on the relationships between subjective norms and perceived behavioral control is insignificant, the research study indicates that self-efficacy moderates the correlation between attitude towards entrepreneurship and start-up intention. Implications for theory and practice: Besides its contributions to entrepreneurship literature, this study also contributes to practices and implications at universities in Vietnam. Originality and value: These findings also illustrate that the theory of planned behavior can be appropriately implemented in the research context of emerging economies such as Vietnam. In addition, the study shows that the relationship between attitude towards entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial intention is moderated by entrepreneurial self-efficacy.

Keywords: entrepreneurial self-efficacy, entrepreneurial intention, the theory of planned behavior, attitude towards entrepreneurship, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control.

INTRODUCTION

Promoting entrepreneurship has recently been seen as the key priority of the Vietnamese government and an impassioned topic in both political and social debates. Antecedents and consequences of venture creation or entrepreneurship have been the interest of many researchers (Nguyen et al., 2018). Entrepreneurship is related to both economic and social activities (Kot et al., 2016). Governments, scholars, and policymakers take into account developing small and medium businesses as they are deemed to be the sustainable development paths in many countries (Sivvam, 2012). Grzybowska (2004) defined business venture as individuals’ conscious behavior, which derives from many different conditions, including the economic situation of the country, technological development, cultural value, policy and other social problems. Nevertheless, individuals’ willingness to take risks is perceived as a crucial part of accomplishing business success. Therefore, entrepreneurs play an important role in promoting economic activities, as well as producing added value for society by making profits, creating jobs, and contributing to government budgets (Gaweł, 2010).

Although business venture has been a topic of interest for many researchers in recent years, it is still considered a developing research field within the sphere of management science. In addition, the research methods and literature in this field should be developed (Churchill & Bygrave, 1989; Kot et al., 2016). The research on entrepreneurship is very diversified and is divided into three different areas by Busenitz et al. (2003): Firstly, research on the process of recognition and exploitation of entrepreneurial opportunities; Secondly, research on the characteristics of individuals and teams, the processes associated with the development of intellectual or human capital by entrepreneurship; Thirdly, research on the methods of entrepreneurship and finally, research on cultural, institutional, and environmental factors that facilitate or obstruct entrepreneurship. Among those research areas, the factors that influence an individual’s conduct of entrepreneurship activities are receiving special attention from researchers and state macro governance agencies.

Entrepreneurship is also seen as the process of innovation and creativity, which play a crucial role in producing new services and products, improving productivity and job creation, revitalizing industry, diversifying markets, increasing social welfare and promoting the development of national economies (Guerrero et al., 2008). In the entrepreneurship field, the reason why a person has or does not have entrepreneurial intention has been the interest of many scholars (Moriano et al., 2012; Krueger et al., 1994; Kolvereid, 1996a). With more and more independent contributions to the entrepreneurship field, many researchers have realized the potential value of an intention approach (Bird, 1988) because of the two following reasons. Firstly, entrepreneurial intention formation is not only seen as the first, but also an indispensable stage in the process of starting up an own business (Shook et al., 2003). Therefore, the research on factors affecting intention is considered as a feasible behavioral approach (Wong et al., 2015). Secondly, entrepreneurship is always planned and has a clear intention (Krueger, 2000). This behavior is the result of a process of careful consideration and selection by individuals (Bird, 1988). Empirical studies on various research fields, including entrepreneurship, emphasize that intention is a very effective variable to predict a particular behavior (Armitage & Conner, 2001; Kautonen et al., 2013). Liñán (2008) also states that the correlation between intention and behavior is very high – from 0.9 to 0.96 (Ajzen, 1991).

Moreover, it can be asserted that entrepreneurship is perceived as a conscious, time-consuming, carefully planned, and highly cognitive process (Wu, 2010). Thus, the decision to start a business is considered planned behavior and can be explained by intention models (Zhao et al., 2005). Kolvereid (1996a) also confirmed that the theory of planned behavior, which is proposed by Ajzen (1991), is the most appropriate model to explain and predict entrepreneurial intention. Moreover, Liñán (2008) also argued that the entrepreneurial decision is seen as a complex one, and it requires an intentional cognitive process. Three attendances in the theory of planned behavior, including attitude towards behavior, subjective norms and perceived behavioral control, are perfectly combined to investigate the intention and behavior. In other words, the theory of planned behavior shows the cognitive process to plan and execute an action. For the entrepreneurship field, this is entrepreneurial action. Walker et al. (2013) have pointed out that there are three reasons why the theory of planned behavior is perfectly appropriate for entrepreneurial studies: (i) entrepreneurship is a planned and intended act; nobody engages in starting a business in a timely manner; (ii) subjective norms mentioned in the theory of planned behavior are determined as an independent variable, which influence entrepreneurial intention more than many concepts of general cultural factors in other studies; (iii) this theory has been tested and proven to be feasible when applied to investigate the various type of intention and behavior.

Besides the three attitudinal antecedents in the theory of planned behavior, entrepreneurial self-efficacy has been determined as the best predictor to investigate a person’s entrepreneurial intention and success (Tsai et al., 2014; Liñán, 2008). The previous research has made significant contributions to the entrepreneurship literature. However, questions related to the moderating influences of entrepreneurial self-efficacy on the relationships between these components and entrepreneurial intention in the theory of planned behavior still do not explain it clearly (Tsai et al., 2014). Moreover, personal beliefs regarding the ability to perform a specific behavior have impacts on attitude towards behavior, perceived behavioral control, and intention (Ajzen, 1991). So, entrepreneurial self-efficacy can moderate the links between attitude towards entrepreneurship, perceived behavioral control, and entrepreneurial intention. In addition, some studies show that the relationship between subjective norms and entrepreneurial intention is significant (Kolvereid, 1996a; Krueger et al., 2000; Maresch et al., 2015), while others argue that this correlation is insignificant (Autio et al., 2011; Liñán & Chen, 2009; Solesvik, 2013; Tsai et al., 2014). Nevertheless, attitude towards entrepreneurship and perceived behavioral control can mediate the link between subjective norms and entrepreneurial intention. Thus, this study aims to fill existing research gaps in the business venture literature by answering the following research questions:

RQ1: Does self-efficacy moderate the relationship between attitude towards

entrepreneurship, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control and

entrepreneurial intention among Vietnamese students?

RQ2: Do subjective norms have an indirect effect on entrepreneurial intention

through attitude towards entrepreneurship and perceived behavioral

control?

The contributions this research make to entrepreneurship literature are shown in two manners: Firstly, the moderating role of entrepreneurial self-efficacy on the links between attitude towards entrepreneurship, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control and entrepreneurial intention are presented, while prior studies are only interested in the direct or mediating effects of entrepreneurial self-efficacy on start-up intention (Chen et al., 1998; Markman et al. 2002; Qiao & Hua, 2019; Naktiyok et al., 2010; Shahab et al., 2019; Segal el at., 2005; Tsai et al., 2014). Secondly, while a body of prior studies only focused on exploring the direct link between subjective norms and entrepreneurial intention (Engle et al., 2010; Liñán et al., 2011), this study presents the indirect effect of subjective norms on entrepreneurial intention through attitude towards entrepreneurship and perceived behavioral control.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Many definitions of entrepreneurship and entrepreneur have been developing over recent decades. Schumpeter (1975) argues that entrepreneurs are defined as individuals who produce new products and services to fulfill market demand whereas business venture is seen an important factor for developing a nation’s economy (De Bruin et al., 2006; Schumpeter, 1960). “The environment itself creates entrepreneurship” (Bernat et al., 2016, p. 271) is why running a business requires not only a quick reaction to changes in the complex business environment, but also “it is the process of designing, launching and running a new business” (Timmons, 1990). Kirzner (1985) defines an entrepreneur as someone who is optimistic about the information gained in a way that can discover new entrepreneurial opportunities (Zięba & Golik, 2018). Talpas (2014) considers entrepreneurship to be an identifiable process, via business activities, that indicates effective leadership ability to adapt to a business environment that is characterized by risks, competitions and fluctuations, while entrepreneurs can be defined as owners with a skilful manner, that are likely to utilize limited production resources to produce new products and services, or transforming smaller resources into bigger ones effectively to make a profit (Zimmer & Scarborough, 1996). Indeed, business venture is determined as a cognitive process of running a new business organization (Shane & Venkataraman, 2000), which not only produces new products and services, and create jobs, but also develops the economy of the locality and country. Thus, exploring the roles of entrepreneurship in economic development as well as the effecting factors on entrepreneurship, including entrepreneurial intention, are the interest of many recent studies (e.g., Dvorský et al., 2019; Ključnikov et al., 2019; Rogalska, 2018; Zygmunt, 2018).

Entrepreneurial intention is defined as the intention of an individual to create a new business at a certain time in the future (Thompson, 2009). Gupta & Bhawe (2007) define entrepreneurial intention as a process to guide the planning and implementation of that business creation plan. A person’s entrepreneurial intention comes from the recognition of a business opportunity, taking advantage of available resources to create his own business in a specific business environment context (Kuckertz & Wagner, 2010). Therefore, entrepreneurial intention is considered as the initial planning, which plays a fundamental role for an individual to create a new business in the future. While entrepreneurship is a process of creating a business organization (Gartner et al., 1992), an individual’s entrepreneurial intention plays a decisive role in this process (Lee et al., 2011).

Although intention to become an entrepreneur is only seen as the first phase in a series of acts to engage in a business venture (Bird, 1988), Fishbein and Ajzen (1975) state that intention towards a particular behavior can be perceived as a key indicator of that behavior. In other words, an individual’s intention to perform an action is still determined to be the best antecedent to anticipate his or her actual behavior (Krueger, 2008). Do and Dadvari (2017) also defined entrepreneurial intention as a reasonable state of cognitive process that refers to individuals’ experience and awareness, as well as their interests towards business venture activities as the decision to engage in business is voluntary and conscious (Krueger et al., 2000). A business venture aims to be successful in the long-term and show the prospects related to the economic growth of a country. In their research, Paul and Shrivatava (2016) compared entrepreneurial intention among youth managers in Japan and India, and this study indicates that young managers’ intentions to become entrepreneurs in emerging countries is not always stronger than that of those in developed ones. Entrepreneurial levels in emerging countries such as India, although, are often lower than other developed countries. Thus, it is necessary to promote entrepreneurial activities in emerging countries.

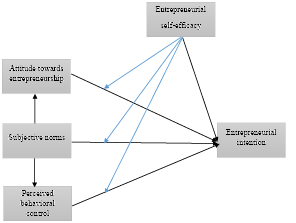

By adopting the theory of planned behavior of Ajzen (1991) and the social cognitive theory of Bandura (1986), the author proposes a research framework to investigate the moderating role of self-efficacy in the cognitive process of entrepreneurship among Vietnamese students, which starts from attitude towards entrepreneurship, subjective norms and perceived behavioral control to entrepreneurial intention. An individual’s intention and behavior is strongly influenced by his or her personal belief to perform a specific task (Bandura, 1986), whereas the control belief has effects on attitude towards behavior, perceived behavioral control, and intention to carry out a behavior (Ajzen, 1991). Thus, entrepreneurial self-efficacy may not only have a direct effect on entrepreneurial intention but it also might moderate the relationships between attitude towards entrepreneurship, subjective norms and perceived behavioral control and entrepreneurial intention. Figure 1 describes the conceptual model to investigate these correlations.

Figure 1. Conceptual framework

The roles of three antecedents in the theory of planned behavior

The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) is an extension of the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA). According to Ajzen (1991), behavioral intention is determined by attitude towards behavior, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. Attitude towards behavior reflects the degree to which an individual has a favorable or unfavorable assessment of a particular behavior, and also depends on an individual’s evaluation of the expected results or outcomes of the behavior. Subjective norms relate to the perception of social pressures by an individual to perform or not perform a specific behavior, and reflect an individual’s perception in terms of salient people encouraging or discouraging them to perform a specific behavior. Perceived behavioral control refers to the beliefs about easiness or difficulty in carrying out a specific task and also shows the perceptions of the availability of resources, supports or barriers to carry out a behavior.

The theory of planned behavior can be implemented on any actual behavior that requires a specific amount of planning (Ajzen, 1991). The reliability of this theory, therefore, has been confirmed as robust in exploring intention and actual behavior in a body of various research fields. Intention and behavior to engage in business venture is complex and stems from an intricate mental process. As a result, the theory of planned behavior has been frequently employed to explain this mental process that results in creating a firm (Liñán, 2008).

In the entrepreneurship literature, many scholars are interested in discovering the linkage between the three attitudinal components in the theory of planned behavior (attitude towards entrepreneurship, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control) and intention to become entrepreneurs (Kolvereid, 1996a; Krueger et al., 2000). Although scholars confirmed that attitude towards entrepreneurship and perceived behavioral control have strong effects on entrepreneurial intention, the findings of existing studies on the direct linkage between subjective norms and entrepreneurial intention are rather inconsistent. Some studies show that subjective norms are significantly related to entrepreneurial intention (Kolvereid, 1996b; Kolvereid & Isaksen, 2006; Tkachev & Kolvereid, 1999; Othman & Mansor, 2012; Solesvik, 2013; Maresch et al., 2015), whereas others argue that the link between subjective norms and entrepreneurial intention is insignificant (Autio et al., 2001; Krueger et al., 2000; Miranda et al., 2017; Liñán, 2008; Nabi & Liñán, 2013). Although based on the theory of planned behavior, subjective norms have a direct influence on entrepreneurial intention (Ajzen, 1991), the relationship between subjective norms and entrepreneurial intention should be empirically tested (Krueger et al., 2000). The following hypotheses are proposed to test the effects of attitude towards entrepreneurship, subjective norms and perceived behavioral control on Vietnamese students’ entrepreneurial intention.

H1a. Entrepreneurial intention is positively influenced by attitude towards

entrepreneurship.

H1b. Entrepreneurial intention is positively influenced by subjective norms.

H1c. Entrepreneurial intention is positively influenced by perceived

behavioral control.

Many previous studies indicate that the three attitude components of intention, such as attitude towards entrepreneurship, subjective norms and perceived behavioral control, do not play an equal role in shaping intention in the different research contexts (Kolvereid, 1996b; Krueger et al., 2000; Autio et al., 2001; Liñán & Chen, 2009; Nabi & Liñán, 2013; Tsai et al., 2016; Zaremohzzabieh et al., 2019). Firstly, subjective norms are supposed to have an effect on attitude towards behavior. That is, a person’s attitude towards a behavior is likely to be affected by salient people, including their parents, close friends, teachers, or even successful entrepreneurs (Liñán et al., 2013). In the entrepreneurship field, an individual who has a negative attitude towards creating an enterprise can change his or her attitude towards entrepreneurship more positively if salient people approve and support his or her business activities. Moreover, Al-Rafee & Cronan (2006) argue that many prior studies confirmed that subjective norms are strongly correlated with attitude towards entrepreneurship. In the Vietnamese culture, individuals tend to be affected by people around them, especially their parents, teachers and friends; thus, the link between subjective norms and attitude towards entrepreneurship should be examined. Secondly, perceived behavioral control involves the influence that a personal control belief has on the actual behavior being investigated (Solesvik et al., 2012), whereas Liñán & Chen (2009, p.4) defined perceived behavioral control as “the perception of easiness or difficulty in the fulfillment of the behavior of interest”. Thus, perceived behavioral control reflects a person’s belief about necessary skills, knowledge and abilities required to carry out a specific action and achieve success (Miranda et al., 2017). This concept also refers to the perception about the control ability of the behavior (Liñán & Chen, 2009). Bandura (1986) considers that social beliefs have a strong effect on sculpting a person’s personal beliefs about their capacity to carry out a particular behavior. In other words, individuals can be swayed to believe that they have enough abilities, skills, and knowledge to achieve success. The verbal encouragement of “I know you will succeed” from people around them can inspire an individual to remove any self-doubt and concentrating on his or her tasks to accomplish success (Bandura, 1977). Thus, the effects of subjective norms on attitude towards entrepreneurship and perceived behavioral control should be explored.

H2a. Attitude towards entrepreneurship is positively influenced by

subjective norms.

H2b. Perceived behavioral control is positively influenced by subjective

norms.

The roles of entrepreneurial self-efficacy

The theory of self-efficacy can help to explain why self-efficacy plays an important role in developing entrepreneurship skills and increasing the levels of entrepreneurship motivation. Self-efficacy as a construct is proposed by Bandura (1986) as a person’s judgement of his capacities to execute a specific behavior, and is therefore seen as a largely perceived construct. Lopez and Snyder (2011) state that self-efficacy also reflects an individual’s belief regarding whether he can perform a specific action or not. Indeed, this construct is employed as a reliable predictor of various behaviors. In the context of entrepreneurship, some scholars have defined self-efficacy as the strength of an individual’s belief that he has enough ability to perform entrepreneurial action successfully (Chen et al., 1998; Segal et al., 2005; Tsai et al., 2014), while others have described self-efficacy as entrepreneurs’ self-confidence regarding the accomplishment of an entrepreneurial process (Baum et al., 2001; Baron et al., 1999). However, it is stressed that entrepreneurial self-efficacy and perceived behavioral control are seen as two different concepts. Self-efficacy is defined as a person’s beliefs regarding his abilities to perform a particular task (Tsai et al., 2014; Tavousi et al., 2009), whereas perceived behavioral control involves an individual’s perception of easiness or difficulty to carry out this action (Ajzen, 1991).

The linkage between entrepreneurial self-efficacy and intention to engage in a business venture, including direct and indirect relationships, has been studied in some previous research. It is reported that an individual’s self-efficacy has a positive effect on his intention to set up a business. A high level of entrepreneurial self-efficacy is strongly related to strategic risk-taking (Krueger & Dickson, 1994). Also, it is argued that self-efficacy is a key antecedent of entrepreneurial intention (Krueger, 2000) and entrepreneurial activities (Zięba & Golik, 2018). Individuals, who have high entrepreneurial self-efficacy, have more intrinsic interests in business venture actions, are more willing to make efforts and present persistence when they are faced with challenges and obstacles. So, self-efficacy has impacts on the choices an individual makes, how long he persists at a task and how he feels about it. If an individual feels that the performance of a specific action is within his abilities, he can act, even if this action is difficult, since he perceives the successful completion of the action as a feasible achievement given the belief he has in himself. Indeed, students who have higher entrepreneurial self-efficacy also have higher intention to engage in starting a business (Chen et al., 1998; Liñán et al., 2011; Shinnar et al., 2014; Utami, 2017) and even higher entrepreneurial behavior (Neto et al., 2018). However, the influential degree of entrepreneurial self-efficacy on entrepreneurial intention is different and depends on the particular research context (Krueger et al., 2000; Miranda et al., 2017). Moreover, the indirect links between entrepreneurial self-efficacy and start-up intention are still not explained clearly, and further studies should investigate this relationship (Miranda et al., 2017; Tsai et al., 2014).

A person, who has high self-efficacy, can present higher abilities to pursue and achieve their goals (Bandura, 1997). So, an individual’s intention to run their own business can be influenced by his self-efficacy (Chen et al., 2014). Indeed, entrepreneurial self-efficacy can be considered as an effective indicator to predict the start-up intention and behavior (Lee et al., 2011), while it is argued that self-efficacy has both direct and indirect influences on entrepreneurial intention (Krueger et al., 2000). In this research, the direct link between Vietnamese students’ entrepreneurial self-efficacy and intention to run an own business is considered, and this hypothesis is proposed to test this relationship.

H2c. Entrepreneurial intention is positively influenced by self-efficacy.

Numerous studies, which employ the theory of planned behavior, have confirmed that all three attitudinal antecedents, including attitude towards entrepreneurship, subjective norms and perceived behavioral control, play an important role in forming an intention to become entrepreneurs (Kolvereid, 1996a; Krueger et al., 2000). However, self-efficacy can moderate the relationships between attitude towards entrepreneurship, subjective norms, perceived behavior control, and entrepreneurial intention for the following reasons. Firstly, a person’s intention and behavior are significantly affected by his capacities regarding performing a specific task (Bandura et al., 1980), while perceived behavioral control and attitude towards behavior are influenced by his control beliefs (Ajzen, 1991). Many studies have proved that the correlation between attitude towards entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial intention is really high (Kolvereid, 1996b; Autio et al., 2001; Liñán & Chen, 2009) but a person’s attitude towards behavior can be influenced by his belief in the outcomes of this behavior (Bandura, 1977). Secondly, some studies show that there is no correlation between subjective norms and entrepreneurial intention (Autio et al., 2001; Liñán & Chen, 2009; Krueger et al., 2000), whereas others argue that this relationship is significant (Kolvereid, 1996a; Kolvereid & Isaksen, 2006). Finally, perceived behavioral control reflects an individual’s perception of easiness or difficulty in fulfilling the interested behavior (Liñán & Chen, 2009), which are often not only related to new ventures (Obschonka et al., 2010; Silveira-Perez et al., 2016) but also have a positive influence on the intention to become an entrepreneur (Schaegel & Koenig, 2014). Moreover, an individual, who has strong entrepreneurial self-efficacy, can perceive the low risk related to running a business and can have a high level of willingness to start a business (Liñán, 2008). As a result, the links between attitude towards entrepreneurship, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control and entrepreneurial intention can be moderated by entrepreneurial self-efficacy and the following hypotheses are proposed to test the effects of this moderator.

H3a. The relationship between attitude towards entrepreneurship and

entrepreneurial intention is moderated by self-efficacy.

H3b. The relationship between subjective norms and entrepreneurial

intention is moderated by self-efficacy.

H3c. The relationship between perceived behavioral control and

entrepreneurial intention is moderated by self-efficacy.

METHODOLOGY

Survey and sample

Based on the research purpose, literature review and research framework, the questionnaire is separated into two sections. Firstly, questions are designed to help students show their perception about entrepreneurial self-efficacy, attitude towards entrepreneurship, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control and intention to become entrepreneurs. Secondly, demographic information, including gender, fields of study, participation in entrepreneurship education programs, and type of current professional activities, is required.

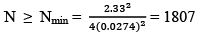

The following formula has been employed to calculate a minimal size of study sample:

(Szajt, 2014, p.40)

Where: Nmin – Minimal size, Uα – Statistical value of the normal distribution table, (1-α) – The confidence level, d– The margin of error (the confidence interval). The confidence level is assumed to be 99% (α = 0.01), which gives the margin of error = 0.0274 (or 2.74%). Moreover, following the report presented by the Ministry of Education and Training, 1,707, 025 students had enrolled in universities in Vietnam (MOET, 2018).

The minimal size of the sample accounts for approximately 1807 students, while the collected sample includes 2218 students. Thus, the sample size is appropriate.

Table 1. Descriptive information of sample demographics

|

Demographic information |

Frequency |

Percent |

|

|

Gender |

Male |

1384 |

62.4 |

|

Female |

834 |

37.6 |

|

|

Fields of study |

Economics and/or Business Administration |

1221 |

54.6 |

|

Engineering and/or another fields |

1006 |

45.4 |

|

|

Participation in entrepreneurship education programs |

Yes |

387 |

17.4 |

|

No |

1831 |

82.6 |

|

|

Current professional activities |

Only learning |

699 |

31.5 |

|

Learning and participating in part-time job |

1080 |

45.9 |

|

|

Learning and running own business |

126 |

5.7 |

|

|

Learning and looking for a secure job |

375 |

16.9 |

|

Note: N=2218

The study collected data from 2218 final-year undergraduate students at universities in Vietnam. Some scholars state that samples of students are rather common in entrepreneurship studies (Autio et al., 2001; Krueger et al., 2000; Liñán & Chen, 2009). However, it is argued that undergraduate students, aged from 25 to 34-years old, often have the highest intention to run their own business (Qiao & Hua, 2019). Indeed, the study only focused on final-year students because they are interested in career choice after graduation at this stage; thus, their start-up intention is likely to be at its highest in the final studying year at university (Autio et al., 2001). 2500 questionnaires were directly distributed to students studying in their final academic year at 14 universities and colleges in the North, Central, and South of Vietnam. The survey not only consisted of direct explanations in terms of the research purposes, but it also included instructions on how to complete the questionnaire. However, only 2218 questionnaires were completed, accounting for 88.72%. The rest of the samples, including 282 questionnaires, were extracted due to incomplete or inadequate answers. Table 1 shows the demographic statistics of respondents.

The results showed that 62.4% respondents were male, and 37.6% were female. In terms of fields of study, approximately 55% of students were studying economics and/or business administration whereas students who were studying engineering and other fields, account for 45.4%. However, only 17.4% of respondents state that they had taken part in entrepreneurship education programs, while 82.6% of students had never participated in these programs. Moreover, 45.9% of students were studying and participating in a part-time job, followed by only studying (31.5%), studying and looking for a secure job (16.9%), studying and running an own business (5.7%).

Analyses

We performed a meta-analytic path analysis using SPSS 22.0 and AMOS 22.0 to investigate the moderating role of entrepreneurial self-efficacy in the relationships between attitude towards entrepreneurship, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, and entrepreneurial intention. The analysis process, with the support of structural equation modeling (SEM), consists of two major stages in order to test the hypothesized linkages. Firstly, Cronbach’s Alpha and exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) were employed to test the reliability, validity of variables as well as the model fit. Secondly, structural equation modeling (SEM) was then utilized to estimate path coefficients of the hypothesized links in the research model.

Scales

All measures in this study were adapted from prior studies, such as entrepreneurial self-efficacy (Tsai et al., 2014), subjective norms (Liñán & Chen, 2009; Kolvereid, 1996b), attitude towards entrepreneurship, perceived behavioral control, and entrepreneurial intention (Liñán & Chen, 2009). The measures were rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). All measures were then subjected to confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) for the purpose of testing the reliability of scales and purification.

Table 2. The reliability of variables

|

Constructs |

Questions |

α |

Component |

||||

|

ESE α = 0.840 |

ESE1. “I show great aptitude for creativity and innovation” |

0.840 |

0.588 |

||||

|

ESE2. “I show great aptitude for leadership and problem-solving” |

0.802 |

0.685 |

|||||

|

ESE3. “I can develop and maintain favourable relationships with potential investors” |

0.796 |

0.795 |

|||||

|

ESE4. “I can see new market opportunities for new products and services” |

0.789 |

0.802 |

|||||

|

ESE5. “I can develop a working environment that encourages people to try out something new” |

0.890 |

0.711 |

|||||

|

EI α = 0.918 |

EI2. “I will make every effort to start and run my own firm” |

0.911 |

0.796 |

||||

|

EI3. “I am determined to create a firm in the future” |

0.895 |

0.841 |

|||||

|

EI4. “I have a very seriously through of starting a firm” |

0.874 |

0.854 |

|||||

|

EI5. “I have the firm intention to start a firm someday” |

0.892 |

0.810 |

|||||

|

ATE α = 0.826 |

ATE2. “A career as an entrepreneur is attractive for me” |

0.816 |

0.733 |

||||

|

ATE4. “If I had opportunity and resources, I’d like to start a firm” |

0.759 |

0.789 |

|||||

|

ATE5. “Being an entrepreneur would entail great satisfactions for me” |

0.765 |

0.769 |

|||||

|

SN α = 0.826 |

SN1. “If I decided to create a firm, my closet family would approve of that decision” |

0.827 |

0.831 |

||||

|

SN2. “If I decided to create a firm, my closes friends would approve of that decision” |

0.758 |

0.862 |

|||||

|

SN3. “If I decided to create a firm, people who are important to me would approve of that decision” |

0.792 |

0.827 |

|||||

|

PBC α = 0.882 |

PBC1. “To start a firm and keep it working would be easy for me” |

0.805 |

0.739 |

||||

|

PBC2. “I am prepared to start a viable firm” |

0.775 |

0.828 |

|||||

|

PBC3. “I can control the creation process of a new firm” |

0.771 |

0.808 |

|||||

|

PBC4. “I know the necessary practical details to start a firm” |

0.788 |

0.708 |

|||||

|

Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy (KMO) |

0.914 |

||||||

|

Sig. of Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity |

0.000 |

||||||

|

Cumulative % |

71.046 |

||||||

Cronbach’s alpha is utilized to test the reliability and the validity of each measure, and the results illustrates that: (i) the correlated item-total correlation of the first item in the “attitude towards entrepreneurship” scale only accounts for 0.352 < 0.4, which is not satisfactory (Nunnally & Brunstein, 1994). Therefore, this item is extracted from the measure of attitude towards entrepreneurship; ii) two items including “I am ready to do anything to be an entrepreneur”, “my professional goal is to become an entrepreneur” in the scale of entrepreneurial intention have a Cronbach’s alpha that is much higher than that of those for full scale of “entrepreneurial intention.” So, two items also should be removed.

Moreover, after examining the reliability of variables by Cronbach’s alpha, 22 items are employed in the exploratory factor analysis (EFA). Results indicate that KMO = 0.926, Sig. (Bartlett’s Test) = 0.000 < 0.001, Initial Eigenvalues = 66.986 > 50%. Nevertheless, PBC6, PBC5, and ATE3 loaded at two-factor groups and only reached 0.313, 0.358, and 0.407 respectively, which are lower than 0.5 (Hair et al.,1988). As a result, these items should be extracted from the scales, called perceived behavioral control and attitude towards entrepreneurship, before conducting confirmatory factor analysis (CFA).

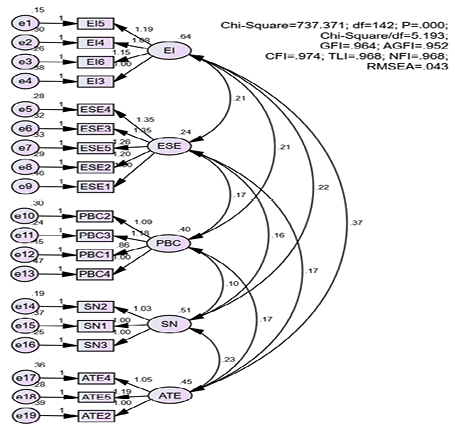

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) is performed to examine the model fit and the internal validity of variables before testing structural model. Research results illustrate that the initial measurement model is satisfactory and shows a great level of fit. χ2 (142) =737.371, P = 0.000, χ2/df = 5.193 (Kettinger & Lee, 1995), CFI = 0.964, AGFI= 0.952, GFI = 0.974, CFI = 0.974, TLI = 0.968, NFI =0.968 > 0.9, and RMSEA = 0.043 (Bentler & Bonnett, 1980). Moreover, the standardized regression weights of all items are higher than 0.5 (λ > 0.5). Thus, the convergent validity of all variables is confirmed.

The average variance extracted (AVE) and composite reliability (CR) is utilized to indicate the reliability, the convergent validity, and discriminant validity of each construct (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988). Table 3 shows that CR values for all scales are seen to be higher than 0.60; the lowest value is 0.818 (attitude towards entrepreneurship-ATE). Also, all AVE values are within the recommended level with a value higher than 0.5. The lowest level of AVE is 0.521 (entrepreneurial self-efficacy-ESE). Thus, the discriminant validity of all variables is represented.

Figure 2. Measurement model (unstandardized estimates)

Table 3. Construct reliability, internal validity, and discriminant validity

|

CR |

AVE |

MSV |

MaxR(H) |

SN |

EI |

ESE |

PBC |

ATE |

|

|

SN |

0.854 |

0.662 |

0.227 |

0.861 |

0.813 |

|

|

|

|

|

EI |

0.918 |

0.739 |

0.472 |

0.930 |

0.393 |

0.859 |

|

|

|

|

ESE |

0.843 |

0.521 |

0.312 |

0.852 |

0.449 |

0.542 |

0.722 |

|

|

|

PBC |

0.825 |

0.544 |

0.312 |

0.845 |

0.220 |

0.410 |

0.559 |

0.738 |

|

|

ATE |

0.818 |

0.601 |

0.472 |

0.826 |

0.476 |

0.687 |

0.534 |

0.395 |

0.775 |

RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

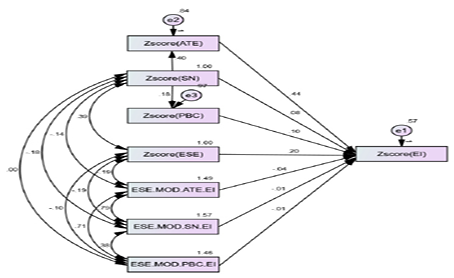

The path coefficients in the structural equation modelling (SEM) analyses (unstandardized estimate model) are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Structural equation modeling (unstandardized estimates)

The results of the hypothesis testing are summarized in Table 4, which shows that hypothesis H1a is supported, because attitude towards entrepreneurship has a positive impact on entrepreneurial intention (β = 0. 443; p-value < 0.001). Interestingly, different from much previous research, this study indicates that the link between subjective norms and entrepreneurial intention is significant (β = 0. 079; p-value < 0.001). In addition, the research results show that entrepreneurial self-efficacy has a more significant impact on entrepreneurial intention (β = 0. 196; p-value < 0.001), compared to perceived behavioral control (β = 0.099; p-value < 0.001). For Vietnamese students, therefore, the beliefs about their abilities, skills, capacities, and knowledge involved in entrepreneurships play a more important role in predicting entrepreneurial intention than their perception of easiness or difficulty related to running own their business. So, the difference between entrepreneurial intention and perceived behavioral control is proved in this study.

Table 4. The results of testing the research hypotheses

|

Hypotheses |

Estimate |

S.E |

C.R |

P |

Conclusion |

|||

|

H1a |

ATE |

→ |

EI |

0.443 |

0.017 |

25.376 |

*** |

Supported |

|

H1b |

SN |

→ |

EI |

0.079 |

0.019 |

4.131 |

*** |

Supported |

|

H1c |

PBC |

→ |

EI |

0.099 |

0.016 |

6.102 |

*** |

Supported |

|

H2a |

SN |

→ |

ATE |

0.404 |

0.019 |

20.797 |

*** |

Supported |

|

H2b |

SN |

→ |

PBC |

0.184 |

0.021 |

8.806 |

*** |

Supported |

|

H2c |

ESE |

→ |

EI |

0.196 |

0.018 |

11.171 |

*** |

Supported |

|

H3a |

ESE*ATE |

→ |

EI |

-0.037 |

0.017 |

-2.160 |

0.031 |

Supported |

|

H3b |

ESE*SN |

→ |

EI |

-0.012 |

0.015 |

-0.777 |

0.437 |

Rejected |

|

H3c |

ESE*PBC |

→ |

EI |

-0.006 |

0.015 |

-0.380 |

0.704 |

Rejected |

Note: N=2218; *** < 0.001; S.E: Standard Deviation; C.R: Critical Ratios.

The study also shows that subjective norms have strong impacts on attitude towards entrepreneurship and perceived behavioral control (β = 0.404, p < 0.001 and β =0.184, p < 0.001 respectively). In addition, subjective norms not only have a direct influence on entrepreneurial intention, but they also indirectly affected entrepreneurial intention through attitude towards entrepreneurship and perceived behavioral control (βindirect SN-EI = 0.197, p < 0.001).

In terms of the moderating role of entrepreneurial self-efficacy in the linkages between attitude towards entrepreneurship, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control and entrepreneurial intention, the study shows that the link between attitude towards entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial intention is moderated by self-efficacy (β = -0.037, p = 0.031 < 0.05), while the moderating role of self-efficacy in the correlations between subjective norms, perceived behavioral control and entrepreneurial intention is not significant (p = 0.437 > 0.05 and p = 0.704 > 0.05 respectively).

Thus, this study shows some interesting insights about the relationship between entrepreneurial self-efficacy and intention. Firstly, being similar to some previous studies (e.g., Tsai et al., 2014; Zięba & Golik, 2018), the study indicates that entrepreneurial self-efficacy is positively related to students’ intention to become entrepreneurs. These results reflect that, although the research is conducted in different contexts, such as Vietnam, Uganda, and Poland, entrepreneurial self-efficacy expressed by student-beginners seems to affect their later start-up behavior in a statistically significant way (Zięba & Golik, 2018). Secondly, whereas almost all prior research only take into account the direct or mediating effects of entrepreneurial self-efficacy on intention, even behavior to become entrepreneurs (e.g., Davidsson & Honig, 2003; Esfandiar et al., 2017; Tsai et al., 2014; Zięba & Golik, 2018), this study reveals that entrepreneurial self-efficacy not only plays an important role in shaping entrepreneurial intention, but it also moderates the linkage between attitude towards entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial intention. So, the existing research gap has been fulfilled (Tsai et al., 2014). Besides, being different from much prior research (e.g., Autio et al., 2001; Liñán & Chen, 2019; Miranda et al., 2017; Tsai et al., 2014), the study illustrates that subjective norms directly influence entrepreneurial intention. Also, attitude towards entrepreneurship and perceived behavioral control partly mediate the linkages between subjective norms and intention to engage in a business venture.

CONCLUSION

This study is expected to contribute to entrepreneurship literature through some of the following perspectives. Firstly, the application of the theory of planned behavior is completely appropriate in the context of Vietnam. The research results also illustrate that the approval or non-approval of salient people such as family members, close friends and teachers plays an important role in Vietnamese students’ intention to run their own business. Analogously to many previous studies, attitude towards entrepreneurship has the strongest effect on entrepreneurial intention, followed by self-efficacy and perceived behavioral control. Secondly, this study shows that self-efficacy and perceived behavioral control are totally different constructs, since the degree of influence level of these factors on entrepreneurial intention is not similar. Thirdly, whereas previous studies only focus on the direct or mediating effects of self-efficacy on entrepreneurial intention, this study shows that although self-efficacy does not play a moderating role in the relationships between subjective norms, perceived behavioral control and entrepreneurial intention, it does moderate the link between attitude towards entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial intention. Finally, the study reveals that the social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1986) can be effectively applied in various study contexts, such Vietnam and Poland, when studies show that entrepreneurial self-efficacy has a direct and strong effect on entrepreneurial intention.

In terms of practical implications, this study might contribute to entrepreneurial education and training at universities and colleges in Vietnam through some of the following perspectives. On the one hand, the study results illustrate that attitude towards entrepreneurship plays the most crucial role in shaping intention to run their own business among Vietnamese students. Thus, educators, lecturers, and policymaker should have appropriate solutions to promote students’ positive attitude towards entrepreneurship. Teachers can devote their time as well to efforts to impart business knowledge and skills to their students. However, ‘attitude’ is the most strongly related to ‘intention’; therefore, teachers should figure out the most effective teaching methods to enhance a positive attitude towards entrepreneurship among students. Sharing the successful experiences of actual entrepreneurs, for example, can contribute to the development of students’ positive attitude towards entrepreneurship. On the other hand, the results of this study show that entrepreneurial self-efficacy is also determined as a powerful variable, which does not only have the direct and strong influence on entrepreneurial intention, but also moderates the relationship between attitude towards entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial intention. Therefore, in the case of determining entrepreneurial intention as an outcome of entrepreneurial education, finding appropriate approaches to enhance entrepreneurial self-efficacy becomes more necessary. Bandura (1989) indicates that four methods should be employed to increase a person’s entrepreneurial self-efficacy, such as role models, social encouragement, mastery experiences, and state of physiology. Starting and managing small projects, extra-scholar, and sharing successful stories and experiences of businessmen in entrepreneurial education, therefore, can encourage students to believe in their business skills, entrepreneurial abilities, and knowledge. Finally, the results indicate that subjective norms are not only directly related to entrepreneurial intention but that the linkage between subjective norms and entrepreneurial intention are also partially mediated by attitude towards entrepreneurship and perceived behavioral control. The results reflect that entrepreneurial intention is referred to as social pressure. In other words, the opinion of other people play an important role in shaping students’ entrepreneurial intention. Apart from parents, students’ entrepreneurial intention is also encouraged by their university environment, including close friends and lecturers. Thus, universities can be responsible for fostering students’ entrepreneurial intention through some effective ways such as supporting business start-up movements and start-up clubs in colleges.

Based on the findings of this study, several directions can be conducted for further research. Firstly, biases and yield new findings can be identified as a result of expanding the research sample. Secondly, a stratified random sampling method should be utilized in any further studies to improve the level of significance. Thirdly, apart from exploring the moderating role of entrepreneurial self-efficacy in the linkages between the three components in the theory of planned behavior with the intention to become entrepreneurs, it is necessary to investigate both the moderating and mediating roles of personal factors that are involved in the process of shaping entrepreneurial intention in emerging economies, such as Vietnam. Finally, the conceptual framework should be expanded, by adding new variables such as social capital, entrepreneurial education, regulatory and normative factors, entrepreneurship ecosystem, to be conducive to the development of entrepreneurship literature and implications.

Acknowledgement

This research is funded by National Economics University, Hanoi, Vietnam.

References

Armitage, C.J., & Corner, M. (2001). Efficacy of the theory of planned behavior: A meta analytic review. British Journal of Social Psychology, 40(4), 471-499. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466601164939

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

Al-Rafee, S., & Cronan, T.P. (2006). Digital piracy: Factors that influence attitude toward behaviour. Journal of Business Ethics, 63(3), 237-259. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-005-1902-9

Autio, E., H. Keeley, R., Klofsten, M., Parker, G. C., & Hay, M. (2001). Entrepreneurial intent among students in Scandinavia and in the USA. Enterprise and Innovation Management Studies, 2, 145–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/14632440110094632

Bandura, A. (1977). Social Learning Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ.: Prentice Hall.

Bandura, A., Adams, N. E., Hardy, A. B., & Howells, G. N. (1980). Tests of the generality of self-efficacy theory. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 4(1), 39–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01173354

Bandura, A. (1986). The Social Foundations of Thought and Action. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Baron, R. A., & Markman, G. D. (1999). Cognitive mechanisms: Potential differences between entrepreneurs and non-entrepreneurs. In P. D. Reynolds & W. D. Bygrave (Eds.), Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research. Wellesley: Babson College.

Baum, J. R., Locke, E. A., & Smith, K. (2001). A multidimensional model of venture growth. Academy of Management Journal, 44(2), 292–303. https://doi.org/10.5465/3069456

Bentler, P. M., & Bonett, D. G. (1980). Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin, 88(3), 588–606. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.88.3.588

Bernat T., Maciejewska-Skrendo A., & Sawczuk M. (2016). Entrepreneurship-Risk-Genes, experimental study. Part 1- entrepreneurship and risk relation. Journal of International Studies, 9(3), 207-278. https://doi.org/10.14254/2071-8330.2016/9-3/21

Bird, B. (1988). Implementing entrepreneurial ideas: The case for intention. Academy of Management Review, 13(3), 442–453. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1988.4306970

Busenitz, L. W., West, G. P., Shepherd, D., Nelson, T., Chandler, G. N., & Zacharakis, A. (2003). Entrepreneurship research in emergence: Past trends and future directions. Journal of Management, 29(3), 285–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0149-2063_03_00013-8

Chen, C. C., Greene, P.G. & Crick. A. (1998). Does entrepreneurial self-efficacy distinguish entrepreneurs from managers? Journal of Business Venturing, 13(4), 295-316.

Churchill, N., & Bygrave, W. D. (1989). The entrepreneurship paradigm (I): A philosophical look at its research methodologies. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 14(1), 7–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/104225878901400102

Davidsson, P., & Honig, B. (2003). The role of social and human capital among nascent entrepreneurs. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(3), 301–331. doi:10.1016/s0883-9026(02)00097-6.

Dvorský, J., Petráková, Z., Zapletalíková, E., & Rózsa, Z. (2019). Entrepreneurial propensity index of university students. The case study from the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Poland. Oeconomia Copernicana, 10(1), 173-192. https://doi.org/10.24136/oc.2019.009

De Bruin, A., Brush, C. G., & Welter, F. (2007). Advancing a framework for coherent research on women’s entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 31(3), 323–339. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2007.00176.x

Do, B. & Dadvari, A. (2017). The influence of the dark triad on the relationship between entrepreneurial attitude orientation and entrepreneurial intention: A study among students in Taiwan University. Asia Pacific Management Review, 22, 185-191. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.apmrv.2017.07.011

Esfandiar, K., Sharifi-Tehrani, M., Pratt, S., & Altinay, L. (2017). Understanding entrepreneurial intention: A developed integrated structural model approach. Journal of Business Research, 94, 172-182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.10.045

Engle, R. L., Dimitriadi, N., Gavidia, J. V., Schlaegel, C., Delanoe, S., Alvarado, I., He, X., Buame, S., & Wolff, B. (2010). Entrepreneurial intent: A twelve-country evaluation of Ajzen’s model of planned behavior. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior and Research, 16(1), 36-58. https://doi.org/10.1108/13552551011020063

Fayolle, A., & Liñán (2013). The future of research on entrepreneurial intention. Journal of Business Research, 67, 663-666. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.11.024

Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Gartner, W. B., Bird, B. J., & Starr, J. A. (1992). Acting as if differentiating entrepreneurial from organizational behavior. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 16(3), 13–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/104225879201600302

Gaweł, A. (2010). The relationship between entrepreneurship and unemployment in the business cycle. Journal of International Studies, 3(1), 59-69.

Griffiths, M. D., Kickul, J. & Carsrud, A. L. (2009). Government bureaucracy, transactional impediments and entrepreneurial intentions. International Small Business Journal, 27(5), 626–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242609338752

Grzybowska, A. (2014). Przedsiębiorczość jako determinanta konkurencyjności przedsiębiorstw. Przedsiębiorczość i Zarządzanie, 2, 19-28.

Guerrero, M., Rialp, J., & Urbano, D. (2008). The impact of desirability and feasibility on entrepreneurial intentions: A structural equation model. The International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 4(1), 35–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-006-0032-x

Gupta, V. K., & Bhawe, N. M. (2007). The influence of proactive personality and stereotype threat on women’s entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 13(4), 73–85. https://doi.org/10.1177/10717919070130040901

Hair Jr., J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (1998). Multivariate Data Analysis (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Kautonen, T., van Gelderen, M., & Tornikoski, E. T. (2013). Predicting entrepreneurial behaviour: A test of the theory of planned behavior. Applied Economics, 45(6), 697-707. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2011.610750

Ključnikov, A., Civelek, M., Čech, P., & Kloudová, J. (2019). Entrepreneurial orientation of SMEs’ executives in the comparative perspective for Czechia and Turkey. Oeconomia Copernicana, 10(4), 773-795. https://doi.org/10.24136/oc.2019.035

Krueger, N. F. (2000). The cognitive infrastructure of opportunity emergence. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 24(3), 5–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540 -48543-8_9.

Krueger, N. F., Reilly, M. D., & Carsrud, A. L. (2000). Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Business Venturing, 15(5), 411-432. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(98)00033-0

Krueger, N. F., & Brazeal, D. V. (1994). Entrepreneurial potential and potential entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 18(3), 91–104. https://doi.org/10.1177/104225879401800307

Kolvereid, L. (1996a). Organizational employment versus self-employment: Reasons for career choice intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 20(3), 23–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/104225879602000302

Kolvereid, L. (1996b). Prediction of employment status choice intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 21(1), 47–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/104225879602100104

Kolvereid, L., & Isaksen, E. (2006). New business start-up and subsequent entry into self-employment. Journal of Business Venturing, 21, 866–885. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2005.06.008.

Kot, S., Meyer, N., Broniszewska, A. (2016). A cross-country comparison of the characteristics of polish and south african women entrepreneurs. Economics and Sociology, 9(4), 207-221. https://doi.org/10.14254/2071-789X.2016/9-4/13.

Kuckertz, A., & Wagner, M. (2010). The influence of sustainability orientation on entrepreneurial intentions - investigating the role of business Experience. Journal of Business Venturing, 25, 524-539. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2009.09.001

Kirzner, I. (1985). Discovery and the Capitalist Process. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lee, L., Wong, P. K., Foo, M.D., & Leung, A. (2011). Entrepreneurial intentions: The influence of organizational and individual factors. Journal of Business Venturing, 26, 124–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2009.04.003

Liñán, F. (2008). Skill and value perceptions: How do they affect entrepreneurial intentions? International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 4(3), 257- 272. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-008-0093-0

Liñán, F., Santos, F. J., & Fernández, J. (2011). The influence of perceptions on potential entrepreneurs. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 7(3), 373-390. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-011-0199-7

Liñán, F., Nabi, G., & Krueger, N. (2013). British and Spanish entrepreneurial intentions: A comparative study. Revista De Economia Mundial, 33, 73-103.

Liñán, F. & Chen, Y. W. (2009). Development and cross-cultural application of a specific instrument to measure entrepreneurial intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(3), 593-617. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2009.00318.x

Lopez, S. J., & Snyder C. R. (2011). The Oxford Handbook of Positive Psychology (2nd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press.

Markman, G. D., Balkin, D. B., & Baron, R. A. (2002). Inventors and new venture formation: The effects of general self-efficacy and regretful thinking. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 27(2), 149–166. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-8520.00004

Maresch, D., Harms, R., Kailer, N., & Wimmer-Wurm, B. (2015). The impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intention of students in science and engineering versus business studies university programs. Technological Forecasting & Social Change, 104, 172-179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2015.11.006

Miranda, F. J., Chamorro-Mera, A., & Rubio, S. (2017). Academic entrepreneurship in Spanish university: An analysis of determinants of entrepreneurial intention. European Research on Management and Business Economics, 23, 113-222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iedeen.2017.01.001

Moriano, J. A., Gorgievski, M., Laguna, M., Stephan, U., & Zarafshani, K. (2012). A Cross-cultural approach to understanding entrepreneurial intention. Journal of Career Development, 39(2), 162–185. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894845310384481

MOET. (2018). Education and Training Statistical Year-Book Academic Year 2017-2018. Hanoi: Vietnam Education Publishing House.

Nabi, G., & Liñán, F. (2013). Considering business start-up in recession time: The role of risk perception and economic context in shaping the entrepreneurial intent. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior and Research, 19(6), 633-655. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-10-2012-0107

Naktiyok, A., Nur Karabey, C. & Caglar Gulluce, A. (2010). Entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurial intention: the Turkish case. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 6, 419–435. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-009-0123-6

Neto, R., Rodrigues, V., Steward, D, Xiao, A., & Snyder, J. (2018). The influence of self-efficacy on entrepreneurial behavior among K-12 teacher. Teaching and Teacher Education, 72, 44-53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2018.02.012

Nguyen, V.T., Nguyen, T.L., & Nguyen, B.N. (2018). Fostering entrepreneurship among academia: A study of Vietnamese scientist commercialization. Journal of Economics and Development, 20(3), 88-102. https://doi.org/10.33301/JED-P-2018-20-03-06

Obschonka, M., Silbereisen, R. K., & Schmitt-Rodermund, E. (2010). Entrepreneurial intention as developmental outcome. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 77(1), 63–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2010.02.008

Othman, N., & Mansor, M. (2012). Entrepreneurial intentions among polytechnic students in Malaysia. International Business Management, 6(4), 517-526. https://doi.org/10.3923/ibm.2012.517.526

Paul, J., & Shrivatava, A. (2016). Do young managers in a developing country have stronger entrepreneurial intentions? Theory and debate. International Business Review, 25, 1197-1210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2016.03.003

Qiao, X., & Hua, J. (2019). Effect of college students’ entrepreneurial self-efficacy on entrepreneurial intention: Career adaptability as a mediating variable. International Journal of Educational Methodology, 5(3), 305-313. https?doi.org/10.12973/ijem.5.3.305

Rogalska, E. (2018). Multiple-criteria analysis of regional entrepreneurship conditions in Poland. Equilibrium. Quarterly Journal of Economics and Economic Policy, 13(4), 707-723. https://doi.org/10.24136/eq.2018.034

Schlaegel, C., & Koenig, M. (2014). Determinants of entrepreneurial intent: A meta–analytic test and integration of competing models. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 38(2), 291–332. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12087

Shahab, Y., Chengang, Y., Arbizu, A.D., & Haider, M.J. (2019). Entrepreneurial self-efficacy and intention: Do entrepreneurial creativity and education matter? International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 25(2), 259-280. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-12-2017-0522

Schumpeter, J. A. (1975). Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy (3rd edition). New York: Harper and Row.

Segal, G., Borgia, D., & Schoenfeld, J. (2005). The motivation to become an entrepreneur. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour & Research, 11(1), 42–57. https://doi.org/10.1108/13552550510580834

Shane, S., & Venkataraman. S. (2000). The promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research. Academy of Management Review, 25(1), 217-226. https://doi.org/10.2307/259271

Shinnar, R. S., Hsu, D. K., Powell, B. C., & Zhou, H. (2018). Entrepreneurial intentions and start-ups: Are women or men more likely to enact their intentions? International Small Business Journal, 36(1), 60–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242617704277

Silveira-Pérez, Y., Cabeza-Pullés, D., & Fernández-Pérez, V. (2016). Emprendimiento: perspectiva cubana en la creación de empresas familiares. European Research on Management and Business Economics, 22(2), 70–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iedee.2015.10.008

Sivvam, M. (2012). Women Entrepreneurship: An Indian Perspective. Saarbrücken, Germany: LAP Lambert.

Solesvik, M. Z. (2013). Entrepreneurial motivations and intentions: Investigating the role of education major. Education and Training, 55(3), 253-271. https://doi.org/10.1108/00400911311309314

Solesvik, M. Z., Westhead, P., Kolvereid, L., & Matlay, H. (2012). Student intentions to become self-employed: The Ukrainian context. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 19(3), 441-460. https://doi.org/10.1108/14626001211250153

Shook, C.L., Priem, R.L., & McGee, J.E. (2003). Venture creation and the enterprising individual: A review and synthesis. Journal of Management, 29 (3), 379-399. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0149-2063(03)00016-3

Szajt, M. (2014). Przestrzeń w Badaniach Ekonomicznych. Częstochowa: Sekcja Wydawnictw Wydziału Zarządzania Politechniki Częstochowskiej.

Tavousi, M., Hidarnia, A. R., Montazeri, A., Hajizadeh, E., Taremian, F., & Ghofranipour, F. (2009). Are perceived behavioural control and self-efficacy distinct constructs? European Journal of Scientific Research, 30(1), 146–152.

Talpas, P. (2014). Integration of Romani women on the labor market. Polish Journal of Management Studies, 10(1), 198-203.

Thompson, E. R. (2009). Individual entrepreneurial intent: Construct clarification and development of an internationally reliable metric. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(3), 669–694. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2009.00321.x

Tkachev, A. & Kolvereid, L. (1999). Self-employment intentions among Russian students. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 11(3), 269-280. https://doi.org/10.1080/089856299283209

Timmons J.A. (1990). New Venture Creation: Entrepreneurship for the 21st Century. Boston: Irwin/McGraw-Hill.

Tsai, K. H., Chang, H.C., & Peng, C.Y. (2014). Extending the link between entrepreneurial self-efficacy and intention: A moderated mediation model. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 12, 445-463. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-014-0351-2

Utamin, C. W. (2017). Attitude, subjective norms, perceived behavior, entrepreneurship education and self-efficacy towards entrepreneurial intention university student in Indonesia. European Research Studies Journal, 20(24), 475-495.

Walker, J. K., Jeger, M., & Kopecki, D. (2013). The role of perceived abilities, subjective norm and intentions in entrepreneurial activities. The Journal of Entrepreneurship, 22(2), 181-202. https://doi.org/10.1177/0971355713490621

Wu, J. (2010). The impact of corporate supplier diversity programs on corporate purchasers’ intention to purchase from women-owned enterprises: An empirical test. Journal of Business & Society, 49 (2), 359-380. https://doi.org/10.1177/0007650309360759

Wong, K., P., Ho, Y., P., & Autio, E., (2005). Entrepreneurship, Innovation and Economic Growth: Evidence from GEM data. Small Business Economics, 24, 335–350. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-005-2000-1

Zaremohzzabieh, Z., Ahrarri, S., Krauss, S.E., Samah, A.B.A., Meng, L.K., & Ariffin, Z. (2019). Predicting social entrepreneurial intention: A meta-analytic path analysis based on the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Business Research, 96, 264-276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.11.030

Zhao, C. M., Kuh, G.D. & Carini, R. M. (2005). A comparison of international student and American student and American student engagement in effective education practices. The Journal of Higher Education, 76(2), 209-231. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2005.11778911

Zięba, K., & Golik, J. (2018). Testing students’ entrepreneurial self-efficacy as an early predictor of entrepreneurial activities. Evidence from the SEAS project. Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Innovation, 14(1), 91-108. https://doi.org/10.7341/20181415

Zimmerer, T., & Scarborough, N. M. (1996). Entrepreneurship and New Venture Formation. New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Zygmunt, J. (2018). Entrepreneurial activity drivers in the transition economies. Evidence from the Visegrad countries equilibrium. Quarterly Journal of Economics and Economic Policy, 13(1), 89-103. https://doi.org/10.24136/eq.2018.005

Abstrakt

Cel: Niniejsze badanie bada moderującą rolę poczucia własnej skuteczności w poznawczym procesie przedsiębiorczości wśród wietnamskich studentów. W szczególności badanie to bada moderujące skutki poczucia własnej skuteczności przedsiębiorcy na związki między postawą wobec przedsiębiorczości, normami subiektywnymi, postrzeganą kontrolą zachowania i intencją zostania przedsiębiorcą. Metodyka: Adaptując teorię planowanych zachowań i wykorzystując dane zebrane od 2218 studentów w Wietnamie, autor posługuje się meta analityczną analizą ścieżki, aby wykazać, że na intencje przedsiębiorcze silnie wpływa postawa wobec przedsiębiorczości, a następnie poczucie własnej skuteczności i postrzegana kontrola behawioralna. W szczególności do testowania dopasowania modelu i hipotezy zastosowano modelowanie równań strukturalnych (SEM). Wyniki: Badanie wskazuje, że normy subiektywne mają zarówno bezpośredni, jak i pośredni wpływ na intencje przedsiębiorczości. Co więcej, chociaż moderujący wpływ poczucia własnej skuteczności na związki między subiektywnymi normami a postrzeganą kontrolą behawioralną jest nieistotny, badanie wskazuje, że poczucie własnej skuteczności moderuje korelację między postawą wobec przedsiębiorczości a intencją rozpoczęcia działalności. Implikacje dla teorii i praktyki: Oprócz wkładu w literaturę dotyczącą przedsiębiorczości, niniejsze badanie wnosi również wkład do praktyk i implikacji na uniwersytetach w Wietnamie. Oryginalność i wartość: Te odkrycia pokazują również, że teoria planowanego zachowania może być odpowiednio wdrożona w kontekście badawczym gospodarek wschodzących, takich jak Wietnam. Ponadto badanie pokazuje, że związek między postawą wobec przedsiębiorczości a intencją przedsiębiorczą jest moderowany przez poczucie własnej skuteczności.

Słowa kluczowe: poczucie własnej skuteczności przedsiębiorcy, intencje przedsiębiorcze, teoria planowanego zachowania, stosunek do przedsiębiorczości, normy subiektywne, postrzegana kontrola zachowania.

Biographical note

Duong Cong Doanh, Ph.D., MBA, MSc, is working as a lecturer at the Faculty of Business Management, National Economics University, Vietnam. He obtained his MBA degree at CFVG (Vietnam) and he holds an MSc degree at KEDGE Business School, France. He was a Ph.D. student at National Economics University, Vietnam, and University of Szczecin, Poland, on the IMPAKT Program (Erasmus Mundus Scholarship). On November 1st, 2019, he successfully defended his Ph.D. thesis entitled “Applying the Theory of Planned Behavior to explore the factors influencing on university students’ entrepreneurial intention in Vietnam.” Since 2006, he has been working as a coordinator on the SEAMIS program (Student Entrepreneurship and Migration International Survey), which was originally developed by a team of researchers from the University of Szczecin. His areas of scientific interest include entrepreneurship, corporate social responsibility, and sustainable development.

Conflicts of interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Citation (APA Style)

Doanh, D.C. (2021). The moderating role of self-efficacy on the cognitive process of entrepreneurship: An empirical study in Vietnam. Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Innovation, 17(1), 147-174. https://doi.org/10.7341/20211715