Received 4 May 2020; Revised 6 June 2020, 13 July 2020; Accepted 14 July 2020.

This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode).

Maria Corina Barbaros, Ph.D., “Alexandru Ioan Cuza” University of Iasi, Faculty of Philosophy, Social and Political Sciences, International Relations, European Studies Department, Iasi, Corol 1 Bvd, nr 11, Iasi, Romania 700522, e-mail: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it., tel. +040742045109

Abstract

This paper aims to investigate the combined effort of the HR Department and the Marketing and Communication Department to define and implement employer-branding strategies. To obtain the aim, qualitative research was designed to establish the relationship between employer attractiveness, organizational attractiveness and company culture, and to identify to what extent company culture can be communicated through employer branding. Therefore, firstly, the study clarifies the links between employer branding, employer attractiveness, company culture, and the boundaries of these concepts. It then examines how employer branding works concerning company culture attributes, and, finally, the paper draws some conclusions that will address practical implications in the form of employer brand management. The research design was based on qualitative research methods (in-depth interviews and focus groups) applied to stakeholders, employees from the IT industry, and IT companies’ representatives. Subsequently, the qualitative data were processed with Atlas.ti 8 that generated the results and the points under discussion. The data show that when recruiting strategies, respectively, employer-branding strategies are thought separately, as happens most of the time, their efficiency diminishes considerably, and the employer image does not have consistency and attractiveness. To conclude, this study highlights the following practical ideas: a)management teams must have a holistic approach of employer branding, organizational attractiveness, and company culture; b)employer branding, in order to become a useful tool for employees’ retention and recruitment, must be managed by both the HR Department and the Marketing and Communication Department within a coordinated and coherent strategy and c) for employer branding to be efficient, there is a need to leverage HR as a strategic partner and, as a result, employees will be developed into strategic assets of the company.

Keywords: employer branding, company culture, HR strategies, employer attractiveness

INTRODUCTION AND KEY TERMS

There are currently numerous studies that draw attention to the impact of employer-branding and company-culture strategies on employees’ retention and an organization’s attractiveness. The rationale of this study is that although many authors have tried to deepen the impact of these fields, few applied studies analyze these fields’ joint influence (employer branding, employer attractiveness, and company culture) in terms of perceptions about a company. To better understand how each domain operates, there has been an artificial division in terms of their impact. In other words, the image that an employee or a potential employee holds toward a company is an aggregated result of actions related to employer branding, HR strategies, and company culture. It is clear why it was necessary to draw distinct boundaries between these areas (for a better understanding of them, in order to be able to work concretely on some aspects), but an overall perspective is also needed. By firmly dividing and looking at these areas as separate, the efficiency and coherence of a company’s image will be lost. Fortunately, the concept of employer branding is broad enough to incorporate some aspects of the other areas that generate the employer’s image and provide the framework to see the big picture in terms of employer attractiveness.

Firstly, the paper intends to clarify the definitions and links between employer branding, employer attractiveness and organizational culture, and these domains’ boundaries.

One of the most critical challenges in the recruitment process is to optimize the strategy for attracting candidates, since it implies how companies compete for often-limited, highly qualified, or very specifically qualified employees in the labor market, especially in the IT industry (Collins & Kanar, 2013; Fernandez-Araoz, Groysberg, & Noharia, 2009). In this context, companies aim to achieve a certain degree of differentiation and become more competitive in attracting talent through Employer Branding (EB) strategies. It is assumed that, through successfully communicating and promoting the employer’s distinctive and positive qualities and the equivalent employment value proposition (EVB), EB strategies increase the employer attractiveness in the labor market as a whole and, more precisely, among potential skilled candidates that are targeted through the recruitment process.

An employer image, and subsequently, employer branding, is a complex mental construct, and there is a gap in reflecting this complexity. Most authors and studies show how the image is constructed from a certain perspective, but few studies reflect the construction of employer attractiveness as a whole. This paper tries to fill this gap by offering answers to research questions such as: What is the relationship between employer attractiveness and company culture? To what extent can company culture be communicated through employer branding? The study identifies the theoretical model of relations between organizational attractiveness–company culture–employer branding and tries to prove it empirically.

This paper refers to company culture as “the set of shared values, beliefs, and norms that influence the way employees think, feel, and behave in the workplace” (Schein, 1992). It is also useful for our research to take into account the following four functions of organizational culture: it gives members a sense of identity, increases their commitment, reinforces organizational values, and serves as a control mechanism for shaping organizational behavior (Nelson & Quick, 2011). Moreover, company culture determines actions and affects many important management areas such as performance and efficiency, knowledge management, corporate social responsibility (CSR), and innovativeness. A positive and attractive company culture might contribute to organizational attractiveness, and thus it will be a tool for employer-branding strategies.

All along with the study, there are references to Human Resources (HR), a concept that has experienced substantial changes in how it is perceived as a modern industry capability. Most of the time, HR was mainly an operative area within the organization, performing the necessary tasks to manage the human capital to maintain staffing levels and ensure the company’s continuous operations. This was a traditional perspective of HR, but organizations and the market evolved from less production-driven to more employee-centric, and with this new perspective, there is a new role for HR in modern organizations. Consequently, the aim of HR has shifted from the mainly operative, functional role of human capital management to the more strategic role of developing and maintaining a dynamic, educated, and progressive career-oriented staff and inspiring company culture. Authors have operationalized this latter role as Human Resource Development (HRD) and, for the purposes of this study, this perspective will be used. Briefly, HRD is defined as “a series of organized activities conducted within a specified time and designated to produce behavioral change” (Nadler, 1970, p.3) and as “a set of systemic and planned activities designed by an organization to provide its members with the opportunities to learn the necessary skills to meet current and future job demands” (Desimone, Werner, & Harris, 2002, p.5). This research paper is particularly interested in HRD because there are many studies that confirm the role of employees in shaping organizational culture and, implicitly, employer branding. Also, employees are the target and the “actors” of the company culture, which makes a circle of influences between company culture, HRD, and employer branding.

The paper includes four sections, besides this introduction. In the literature review section, the concepts of employer attractiveness, company culture and employer branding are defined, and the most significant research is reviewed. Next, the methodological approaches of the applied study are described. Then, the findings are presented and discussed. At the end, the limitations and conclusions, together with practical implications, are submitted.

Finally, the goal is to position this study at the crossroads of three fields: company culture, employer attractiveness and employer branding and to try to reveal an overview of how these three areas can be merged in order to get a more consistent and attractive organizational image with positive effects on employee retention and head hunting. To sum up, employer branding has joined two significant organizational fields, branding and human resources. Together, they provide a rounded view of attracting and retaining the best employees (Backhaus, & Tikoo, 2004). But it is more than branding and HR. In order to be authentic and convincing, employer branding has to bring in company culture, and this is the emphasis of this study.

LITERATURE REVIEW

This section reviews and discusses the literature considered relevant for the proposed research, namely the studies on employer branding and organizational culture and how the two interact to increase employer attractiveness and trigger positive results.

In the academic literature, the interest in people’s organizational image assessments was initiated by HR and organizational studies scholars. The idea that motived this broad literature was that image perceptions might have an effect on applicants’ attraction to companies (Lievens, 2007). One of the most influential conceptual articles was published in 2001 by Cable and Turban (2001). They determined a research trend on better understanding the image that job seekers have about employers, and the employer’s image antecedents, dimensions, and consequences (Breaugh & Starke, 2000). During the same period, the academic interest in employer image was reflected by the development of employer branding as one of the main topics in HR practice.

While company culture and HRD have been discussed in the literature for a very long time, the notion of employer branding is relatively newer (about 20 years of research in this area). The initial definition of Ambler and Barrow still captures the essence of employer branding, which is “the package of functional, economic and psychological benefits provided by employment and identified with the employing company” (Ambler & Barrow, 1996, p. 187). An employer brand should stand for an organization as a potential employer, and the organization should aim to position itself as an employer that provides a superior employment experience against competitors, to enable competitive advantage (Love & Singh, 2011). It has been identified that a powerful employer brand should consist of rewards, salary, benefits, career progression, and scope for added value (Jain & Bhatt, 2015), so it incorporates both instrumental and symbolic elements.

The academic community widely accepted that employer branding has the ability to retain the right individuals, and EB is particularly important to companies in regard to organizational success (Backhaus & Tikoo, 2004). There is an on-going interest in the topic and research supports the fact that a business’s success can depend on its ability to attract and retain employees, thus acknowledging the growing value of employer branding (Gilliver, 2009; Sengupta, Bamel, & Singh, 2015). Other research findings have shown that the argument behind EB’s strength and value comes from the advantages attained from a successful brand: differentiation and loyalty (Collins & Kanar, 2013). This means that an employer brand will be able to distinguish itself from the competitors and establish an emotional bond with potential candidates (Davies, 2008). Thus, the value of a brand is associated with its degree of awareness/recognition and the image it conveys to people (Holliday, 1997).

Studies point out that EB strategies and activities support the organization’s attractiveness to the extent that they set up, communicate, and reinforce the company’s positive attributes as an employer (Edwards, 2010). Moreover, EB is not only related to recruitment because “where traditional recruitment strategies are short-term, reactive, and subject to job openings, employment branding is a long-term strategy designed to maintain a steady flow of skills in the organization” (Srivastava & Bhatnagar, 2010, p. 26).

Nevertheless, despite this expanding visibility and relevance for companies, there are few academic studies on the subject of EB associated with company culture. Furthermore, literature has been mainly centered on concepts and results achieved through EB like better recruitment outcomes, more differentiation, stronger emotional bonds, and financial returns (Sokro, 2012). Research on company culture attractiveness dimensions used in EB strategies is still occasional and limited (Biswas & Suar, 2014). Thus, one of this paper’s contributions is to investigate the role of company culture in relation to the employer attractiveness.

Studies have concluded that EB is an essential part of business success, but scholars are still trying to find the best ways to measure EB effects and to reach a common ground in understanding the EB processes and components (Berthon, Ewing, & Hah, 2005). The latter is a difficult goal because an organization’s employer image is a blend of mental representations and correlations regarding that organization as an employer. This means that an employer’s image is made up of precise attributes that a job seeker or a current employee associates with the organization. Collins and Kanar (2013) refer to these relations as complex associations because they are not unconscious and call for more cognitive processing. Although there were various formulated and tested categories of these attributes, the most well-known and longstanding categorization pertaining to marketing is the distinction between instrumental, symbolic, and experiential attributes (Keller, 1993). A lot of research effort was allocated to identify the role and different aspects of instrumental attributes related to employer branding and employer attractiveness. Instrumental attributes represent the job seekers’ preferences for the more concrete advantages of an organization with functional, practical value (e.g., location, pay, benefits, or advancement opportunities). Even if instrumental attributes are an essential part of an employer brand’s attractiveness, this study is focused more on symbolic attributes because they are related to company culture and allow us to draw some conclusions about the attractiveness of organizational cultures that can be projected through employer branding.

Research has already demonstrated the significance and the value of symbolic attributes, and HR scholars have developed various instrumental-symbolic frameworks (Lievens & Highhouse, 2003). The main assumption is that these attributes designate interpretations that describe the organization in terms of subjective and intangible attributes. They express the symbolic company information and people are attracted to these characteristics to state their values or to impress others (Highhouse, Zickar, Thorsteinson, Stierwalt, & Slaughter, 2007). For example, people might refer to some organizations as hip and others as prestigious or other subjective evaluations. These symbolic attributes are called ‘organization personality trait inferences’ in the specialized literature (Slaughter, Zickar, Highhouse, & Mohr, 2004). Slaughter et al. (2004, p. 86) proposed a definition of organization personality as “the set of human personality characteristics perceived to be associated with an organization.” The biggest challenge is to measure or to capture these symbolic inferences. The present study tries to contribute to this body of literature and takes into account various scales used to measure symbolic attributes. A reference scale is the one developed by Lievens and Highhouse (2003), which aims to measure Innovativeness, Competence, Sincerity, Prestige, and Ruggedness. Other renowned examples are Otto, Chater, and Stott’s (2011) four-dimension scale (Honesty, Prestige, Innovation, and Power) and Davies, Chun, Vinhas da Silva, and Roper’s (2004) five-dimension corporate character scale (Agreeableness, Enterprise, Chic, Competence, and Ruthlessness).

Most of the studies examined employer image measures of particular attributes that candidates or employees associate with the employer brand. In addition to the company’s attributes approaches, some scholars have tried to understand EB from a more holistic perspective. Collins and Stevens (2002) argued that perceptions/evaluations regarding an employer could be divided into both perceived attributes and attitudes. Whereas the perceived attributes follow the instrumental perspective, Collins and Stevens outlined that attitudes are “general positive feelings that job seekers hold toward an organization” (Collins & Stevens, 2002, p.43). Following this idea, DelVecchio, Jarvis, Klink, and Dineen (2007) found that these associations are more automatic and thus described them as “surface” employer image associations.

From a conceptual perspective, it is important to stress that this holistic approach does not theorize employer image as consisting of a set of specific elements and knowledge structures. This perspective mostly aims to capture the common feelings, perceptions, and attitudes toward the organization (Gardner, Erhardt, & Martin-Rios, 2011; Kucharska & Kowalczyk, 2019). That is also the rationale why authors like Collins and Kanar (2013) equate these surface employer image associations with organizational attractiveness. In most studies that were based on the holistic aggregated view, employer image was operationalized as an indicator of overall organizational attractiveness (Highhouse et al., 2003), which served as a dependent variable. In contrast, the measures of particular attributes (salary, benefits, or advancement opportunities) were usually considered as independent variables.

As a distinct topic, employer attractiveness has received extensive research attention in the latest years (Aiman-Smith, Bauer, & Cable, 2001) and has focused on the benefits that potential candidates foresee they could obtain by working in a specific company (Pingle & Sharma, 2013). Hence, the main findings support the fact that employer attractiveness influences the recruitment processes and professionals’ retention (Helm, 2013; Gatewood, Gowan, & Lautenschlager, 1993). Other studies argue that attractiveness concerns “an attitude or expressed general positive affect toward an organization, toward viewing the organization as a desirable entity with which to initiate some relationship” (Aiman-Smith, Bauer & Cable, 2001, p.221). The authors also point out that attractiveness is confirmed when people are looking for a chance to participate in the recruitment processes in a particular organization. This perspective emphasizes that fostering an employer’s attractiveness in the recruitment process is different from the employer attractiveness as an aggregated image (Breaugh & Starke, 2000). It means that, while in the primary stage of the recruitment process the aim is to attract candidates for specific available openings at a given time, organization attractiveness must be constantly worked on so that the company becomes a valued and attractive employer in the labor market; this will, in turn, enable the recruitment process (Collins & Stevens, 2002).

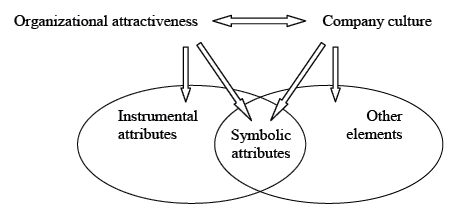

Organizational attractiveness, company culture and symbolic attributes

The literature review section synthesized the research on organizational attractiveness and employer branding. It is important for the objectives of this study to introduce the Employer Attractiveness Scale developed by Berthon and his colleagues (2005). The scale consists of five attractiveness attributes and it evaluates to what extent the organization supports these values: 1) Interest Value: a challenging and inspiring job, with innovative working practices and projects, in an environment that encourages creativity and innovation; 2) Social Value: a positive and enjoyable social and relational environment; 3) Economic Value: wages, benefits package, job security, and advancement opportunities; 4) Development Value: offers recognition, self-esteem and trust, skills development and career-enhancing opportunities; 5) Application Value: the prospect to apply expertise and pass on knowledge to others, in a customer-oriented and humanitarian workplace (Reis, 2016). Each attractiveness attribute can be further operationalized in specific indicators and then applied to specific organizational contexts.

The advantage of this scale is that it offers a complex, holistic, but also a measurable perspective of organizational attractiveness. This study is interested in symbolic attributes, or inferred traits, which constitute the second dimension of employer image attributes and allow employees “to maintain their self-identity, to enhance their self-image, or to express themselves” (Lievens & Highhouse, 2003, p.79). Symbolic attributes are included in the Social Value and Development Value of Berthon’s scale. Moreover, company culture has been partly operationalized through what we call symbolic attributes. This is why, when we try to ascertain the relation between organizational attractiveness and company culture, we look at symbolic attributes and the way they are invoked and interpreted by job seekers and other stakeholders.

Figure 1. Symbolic attributes’ relations

Source: own work, based on empirical research carried out in 2020.

Furthermore, studies have demonstrated that symbolic attributes may be particularly relevant and differentiate an employer more from its competitors than instrumental attributes do (Lievens & Highhouse, 2003; Srivastava & Bhatnagar, 2010). Our study complements this perspective, which is insufficiently empirically documented.

Recruitment (as a topic of HR studies) and organizational attractiveness research interconnects with employer-branding research but takes a broader perspective than the EB research does (Gardner, Erhardt, & Martin-Rios, 2011). Therefore, organizational attractiveness is facilitated by employer branding, which will partially valorize company culture. This is the theoretical model of the relation between the three concepts that we try to prove empirically throughout the proposed qualitative research. In order to do this, the study takes into account Lievens’s perspective (2007), which states that EB requires three stages: 1) a powerful and distinctive employer value proposition (EVP), which includes attributes to be offered to future and current employees, is designed; 2) this EVP is communicated inside and outside the organization; 3) the implementation phase, that is, to actually carry out the promises made in the EVP, in terms of the attraction attributes.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

As it was previously stated, the aim is not to create new concepts. Rather, the study intends to increase clarity among the already existing constructs and to see how they can work together. First, the employer branding was defined and differentiated from related concepts, also identifying the common grounds of these concepts. Next, in the literature review, it was examined how employer image can be measured, distinguishing between particular elements of the image and the overall image. The article then described the outcomes of employer image (i.e., what is the purpose of investing in employer image?) and what is employer attractiveness. Next, the article approaches qualitative research analysis. The aim is to highlight how the employer image is formed (processes, links between different elements of the company’s image) and the share of company culture in a company’s overall image. The study ends with practical suggestions (i.e., how can companies manage the images they project?) for employer brand management.

Within the specialized literature, the external employer brand can be mapped to the employer image (i.e., an outsider’s perception of attributes related to an organization as an employer), whereas the internal employer brand (i.e., an insider’s perception of attributes related to an organization as an employer) corresponds to the company’s identity. External employer branding is then considered to be a synonym for employer image management. This study refers only to the external employer brand and the findings are relevant only for the external component of the employer branding. For a shorter expression, the paper refers to external employer brand as employer brand (employer branding).

The entire study tries to build arguments for the following research questions (RQ):

RQ1: What is the relation between employer branding, organizational

attractiveness, and company culture?

RQ2: To what extent can company culture be communicated through

employer branding?

In order to do that, the research propositions (RP) are:

RP1: Employer branding beats head hunting.

RP2: The organizational culture of a company is also attractive for those

outside the company.

RP3: The image of an employer is built primarily by the way employees talk

about the company.

This study uses qualitative methods because the research questions are primarily concerned with the process rather than the outcomes of the employer branding, company culture, and organizational attractiveness. Thus, qualitative methods have been chosen as the best answer for our RQs because we were interested in identifying the meaning, in other words, how stakeholders make sense of the three concepts under scrutiny. Qualitative research has mostly a descriptive and inductive approach, which offers the researcher the opportunity to build abstractions, concepts, and theories from details. Our aim was specifically to establish a theoretical model of relations between EB, organizational attractiveness, and company culture.

Empirical research context

The qualitative research was conducted in Iasi, a city in Eastern Romania where the IT industry is experiencing accelerated development. In 2016, there were 786 IT&C companies in Iasi. In 2018 there were approximately 100 additional companies registered, and in 2019 over 950 companies. The total turnover has increased from 264 million euros (2016) to 339 million euros (2019). And the number of employees has increased significantly, from 8,800 (2016) to 12,000 (2019).

Iasi is the second-largest city in Romania and one of the largest university centers with approximately 60,000 students, and salaries in the IT industry below the average of the capital and the IT industry in Western Europe. These conditions led to the rapid development of the IT industry and the number of employees needed for the constantly expanding market. The demand for IT employees is higher than the supply of the profile faculties, and this determines fierce competition between the employers in the field. Given that instrumental attributes are almost similar, the competition moves to symbolic attributes; thus, employer branding and company culture become extremely relevant aspects.

The research context offers a perspective on how employer branding and company culture perform in developing cities in ex-communist European countries. Most studies that have correlated employer branding and company culture have been conducted in Western Europe or America, the conclusions being influenced by the context of consolidated capitalist economies. This study offers a perspective from Eastern Europe, where employer branding is still trying to consolidate its role.

Data collection and background of the interviewees

In order to pursue the research objective, i.e. the identification of a theoretical relation model between employer branding, organizational attractiveness, and company culture, a qualitative methodology with mixed methods of research using in-depth semi-structured interviews and focus groups was adopted. The reason for combining the two qualitative research methods is that we wanted to have a more comprehensive perspective on how the subjects correlate the two elements – employer branding and company culture. In-depth interviews offer useful and relevant insights. They have the advantage of no potential distractions or peer-pressure dynamics that can sometimes emerge in focus groups. Because in-depth interviews can potentially be so insightful, it is possible to identify highly valuable findings quickly.

On the other hand, focus groups are a useful method to confirm the analysis with a wide variety of respondents’ profiles. Also, focus groups are the best way to exchange viewpoints and discuss disagreements between stakeholders or target analyzed groups. These dynamics will not be captured in a face-to-face interview and that is the reason why we mixed the research methods.

The sample consisted of professionals who work mainly in the IT industry or close to this industry. The research team conducted six in-depth, semi-structured interviews with IT company representatives (from four firms), seven in-depth interviews with various IT stakeholders (one journalist specialized in the IT industry, one NGO representative with contacts and interests in the IT industry, three specialists in IT marketing and HR, one representative of the faculties that provide students trained for IT industry needs, one specialist in IT consultancy services). Also, the research team conducted four focus-groups with ten participants in each focus group (one group of students at the Faculty of Computer Science; one group of stakeholders; two groups of IT employees) to test the research propositions and to analyze the dynamics of opinions related to employer branding, organizational attractiveness, and company culture.

The in-depth, semi-structured interviews and focus groups (semi-structured interviews and observer-as-participant) were developed (protocols of questions and the interview schedule), tested and re-assessed before being applied. In addition, various documents (literature reviews, fact sheets about IT dynamics in Iasi, statistics about IT market in Iasi) were analyzed and used to record and cross-reference many aspects of the world under investigation. Each in-depth interview, on average, lasted 50 minutes. In addition to the interview process, the study selected 38 participants to participate in four focus groups. Each focus group lasted 90 minutes and used a semi-structured interview approach. All interviews with IT representatives and stakeholders were conducted within the work location of each participant. The focus groups were conducted in neutral spaces where the participants were invited after being informed about the purpose of the study. Given the nature of the study, access to various interviewees was agreed via a combination of purposive or snowballing sampling, referrals, or some form of the exchange process.

A methodological challenge was the selection of the interviewees and the participants in the focus groups. The criteria that described the interviewees’ background were established to offer the opportunity to select the most suitable participants in the study that can provide useful data regarding the research goal. For the IT representatives (n=6), the criteria were: a) management responsibilities within the firm; b) gender balance; c) responsibilities related to organizational attractiveness and employer branding. Thus, the research team selected a group of 6 interviewees aged between 30-45, with 6-10 years of experience in management and employer-branding areas, in companies with at least 100 employees.

For stakeholders of the IT industry (n=7), the criteria used to select the interviewees were: a) diversity of perspectives pertaining to different areas in which the stakeholders are active; b) direct and constant cooperation with the IT industry. As a result, the research team selected the group previously mentioned (one journalist specialized in the IT industry, one NGO representative with contacts and interests in the IT industry, three specialists in IT marketing and HR, one representative of the faculties that provide students trained for IT industry needs, one specialist in IT consultancy services), which complied with the selection criteria.

Another methodological challenge was to select the participants in the four focus groups. For the stakeholders’ focus group (n=8), the research team used the same criteria as the ones for in-depth interviews with stakeholders. For the students’ focus group (n=10), the selection criteria were gender balance, being students in the last year of computer engineering studies and job seekers. The last two focus groups (n=20) were composed of IT employees that met the following criteria: a) different levels of experience – three entry level, four middle level, three senior; b) gender balance.

To conduct the investigation, in-depth, semi-structured interviews and focus groups were considered appropriate tools to use in order to have a double perspective toward the research objective. On the one hand, the focus groups realized the perspective of those who benefit, evaluate or make professional choices as a result of employer-branding strategies developed by companies, i.e. IT employees and computer engineering/informatics students. On the other hand, the interviews disclosed the perspective of those who develop and implement employer-branding strategies to increase companies’ organizational attractiveness. The study avoided the risk of a one-sided perspective in establishing the theoretical model of relations between employer attractiveness, organizational attractiveness, and company culture.

Protocols of questions and analytic techniques

For data interpretation, the study used Atlas.ti 8, which helps the researcher manage and structure the layers of analysis and facilitates connections across the qualitative data gathered through in-depth, semi-structured interviews, and focus groups. The pieces of data interpreted both inductively and deductively were coded for a more complete understanding of the relations between employer branding, organizational attractiveness, and company culture. While a deductive approach is aimed at testing theory, the inductive approach is concerned with the generation of new theory emerging from the data, in this case the theoretical model of relations between the three concepts.

There are several methods used for managing and evaluating qualitative data circumscribed to two main approaches. Ryan and Bernard (2000) distinguish between the linguistic approach, which treats texts as an object of analysis itself, and the sociological approach, which treats text as a window into the human perceptions and experience. This study is focused on the sociological perspective, specifically. Thus, Ryan and Barnard (2000) argue that there are two categories of written texts, (a) words or phrases produced by techniques for systematic elicitation and (b) free-flowing texts such as narratives or responses to open-ended interview questions. Consequently, this study is concerned with the latter, part b, and the method used for analyzing the data gathered from the field research (interviews and focus groups) is keywords in context (KWIC). As Ryan and Barnard (2000) assert, this technique finds all the places in a text where a particular word or phrase appears and points it out in the context of some number of words before and after it. This method is based on coding qualitative data through tags or labels. The researchers convey units of meaning to the descriptive or inferential information gathered during the study. Therefore, codes were allocated to ‘chunks’ of the text of variable sizes in order to connect or un-connect keywords or phrases within specific research propositions.

The aim of using the codes presented in Table 1 is to describe the data, to retrieve code frequencies, but mostly we are interested in how the discourse enfolds in the data. It is also an actor-network analysis, which is a constructivist approach. In this respect, the actor-network theory tries to describe how material-semiotic networks come together to operate as a whole.

The coding categories were inspired by the Employer Attractiveness Scale (Berthon, 2005) described in the literature review section, particularly by the symbolic attributes that are included in the Social Value and Development Value of Berthon’s scale. As mentioned, the dimensions included in this instrument were preferred because they have already been employed by various international studies, indicating good reliability (Arachchige & Robertson, 2011). Furthermore, Sivertzen, Nilsen, and Olafsen (2013) argued that the instrument involves employer attributes that affect a company’s culture and this, in turn, effectively shapes employer attractiveness among candidates.

Table 1. Code list

|

Research Propositions (RP) |

Code |

Sub-code |

|

RP1 |

Employer branding |

Organizational image Organizational communication |

|

Recruitment process |

Instrumental attributes Symbolic attributes |

|

|

RP2 |

Company culture |

Social value Developmental value |

|

Organizational attractiveness |

Social value Developmental value |

|

|

RP3 |

Employer branding |

Word-of-mouth (WOM) Public events Corporate social responsibility (CSR) Company advertisements |

|

Sources of organizational attractiveness |

Image of company’s projects/field of activity Company’s culture image |

The protocols of questions for in-depth, semi-structured interviews and focus groups proceeded through the following stages: a) apprehension (engendering trust, keeping the informant/s talking in order to get used to the conversation); b) exploration (informants need the opportunity to move through the stage of exploration without the pressure to fully cooperate, they need to get used to the researcher and the theme under scrutiny); c) cooperation (this stage involves complete cooperation based on mutual trust; the informants will no longer fear about offending each other or making mistakes in asking or answering questions).

Also, the protocols of questions encompassed three general categories of questions: a) descriptive questions that enable a person to collect an on-going sample of an informant’s language at the beginning of the interview/focus group; b) structural questions aimed at discovering information about domains, the basic units in an informant’s cultural knowledge; they also allow us to find out how informants have organized their knowledge; c) contrast questions in order to discover the dimensions of meaning which informants employ to distinguish perceptions and ideas related to employer branding, organizational attractiveness and company culture in their world.

Table 2. Sample interview questions mapped to the research questions

|

Research Questions (RQ) |

Interview Questions |

|

RQ1: What is the relation between employer branding, organizational attractiveness, and company culture? |

|

|

RQ2: To what extent can company culture be communicated through employer branding? |

|

FINDINGS

This study’s research design did not involve testing theory but generating theory (through exploratory research) from data. This approach was implemented in order to produce insight and develop an understanding of the relation between company culture and organizational attractiveness from the perspective of IT industry representatives, stakeholders and employees. Assuming that the reality is socially constructed rather than objectively determined, working within such a pattern allowed much more complicated perceptions and subjective connections to be examined. As such, the chosen methodology offered an opportunity to interpret, understand and explain the different constructs and meanings each informant placed on his particular perception of the concepts involved in the theoretical model.

Research Proposition 1 (RP1): Employer branding beats head hunting

This research proposition aims to argue whether successful employer branding can be so effective that it immediately attracts potential candidates who want to be employed in a particular company. The data retrieved from in-depth interviews and focus groups do not support RP1. Employer branding and its results, that is, an attractive image of the organization, do not exceed the efficiency of a recruitment process targeted by HR departments. Most of the questions and discussions with the research subjects were organized around the following questions: Are you constantly looking for employment opportunities at a certain company? Why would you want to be employed at that company? Do you consider that the investment in the external employer branding of the companies leads to the constitution of a pool of potential employees without the need for head hunting? Subjects’ responses were synthesized and organized with Atlas.ti resulting in the relations presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Employer Branding and Recruitment Process Relations

Source: own work, data processed with Atlas.ti 8.

Even if employer branding is not a sufficient condition to facilitate the recruitment process, the subjects’ answers show that employer branding is still a necessary condition for an efficient recruitment process. Respondents associate the attention paid to recruiters with the presentation of instrumental attributes and symbolic attributes. However, it is noteworthy that when respondents analyze what attracts their attention in recruiters’ offers and the attributes listed, they also talk about the company’s overall organizational image. The latter is part of the employer-branding strategy and is brought to the attention of stakeholders and potential employees through organizational communication. As one of the respondents (a middle-level IT employee) remarked:

“We analyze, first of all, the offer and benefits offered, but the image that the company has in the market is also important. If it is a stable company, if it has a good reputation in relation to the way it treats its employees, if it invests in employee training…”

So, even if employer branding cannot automatically ensure employees’ flow, it greatly facilitates the recruitment process. In this RP case, more nuanced research would be necessary to distinguish between internal employer branding and external employer branding and the impact of each in recruitment and retention processes.

Research Proposition 2 (RP2) - The organizational culture of a company is also attractive for those outside the company

Company culture is primarily a topic of interest for the company’s internal management as it ensures team cohesion, pursuing common goals, fulfilling the organization’s mission, and cultivating common beliefs. By formulating this RP, the study tried to verify to what extent, beyond the internal utility that is already demonstrated, company culture attracts attention and facilitates organizational attractiveness. The RP2 is supported by the results of qualitative research.

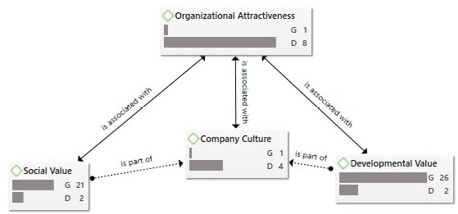

Specifically, to test this proposition, we coded the answers using two of the five dimensions of the Employer Attractiveness Scale (Berthon, Ewing, & Hah, 2005). The Social Value Code includes references to having a good relationship with your colleagues, having a good relationship with your superiors, supporting and encouraging colleagues, and a happy work environment. The Development Value Code included references to feeling more self-confident as a result of working for a particular organization, feeling good about oneself as a result of working for a particular organization, and gaining career-enhancing experience. Both Social Value and Developmental Value are included in the notion of company culture according to the literature and, at the same time, the respondents invoked elements related to social value and developmental value in relation to organizational attractiveness. From here, it can be inferred that the company’s attractiveness also depends on the company culture because the latter is a topic of interest for those outside the company. Figure 3 summarizes the relations created between the qualitative data obtained through interviews and focus groups.

Figure 3 displays information about groundedness (G) and density (D). Groundedness refers to the number of linked quotations, while density counts the number of linked codes. The higher the G-count for a node, the more grounded it is in the data. The higher the D-count for a node, the denser the surrounding network. In Figure 3, G-21 for Social Value and G-26 for Developmental Value suggest, firstly, that the two dimensions are often invoked in the analyzed data.

Figure 3. Organizational Attractiveness and Company Culture Relations

Source: own work, data processed with Atalas.ti 8.

Then, among the two dimensions of company culture, the Developmental Value seems to be more effective for job seekers. This aspect is relevant for designing employer-branding strategies that emphasize organizational culture elements focused on Developmental Value. The association between organizational attractiveness and developmental value is very well summarized by a respondent (senior IT employee):

“Working for an e-health software company gives me significant satisfaction. As a result of the projects we develop in the company, many people will live better, will monitor their health better and this gives me a sense of confidence in myself and in my professional contribution. I feel challenged to develop professionally as much as possible in this field”.

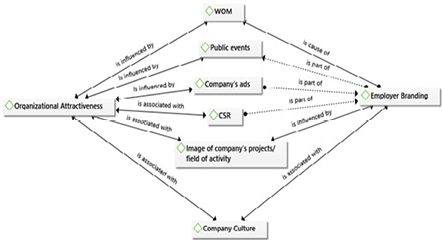

Research Proposition 3 (RP3) - The image of an employer is built primarily by the way employees talk about the company

Company culture places people at the center of its efforts. This proposition raises the question of whether employees of a company are the most efficient vehicle through which organizational attractiveness is created. It is very important for external employer branding to understand what channels to use to strengthen a company’s image. The RP3 is partially supported, in the sense that word-of-mouth (WOM) – the way employees talk about the company they work for – is important, but the image is strengthened as well by the contribution of other elements such as public events, company advertisements, CSR, the company’s projects or field of activity, and company culture as it is confirmed by H2.

One of the interviewed stakeholders summarizes very well the result of the analysis of this research proposal:

“In general, the opinion I have about a company is based less on the company’s direct promotion. I listen to the opinions of its employees, I notice the projects that the company supports or sponsors in the community and the consistency that they have in terms of involvement in city events”.

Figure 4 summarizes how respondents correlated the sources of organizational attractiveness.

Figure 4. Sources of organizational attractiveness

Source: own work, data processed with Atlas.ti 8.

Although the RP3 was a simple one, the research results revealed a larger network of influences on organizational attractiveness that naturally led us back to employer branding. Given that WOM appears to be an important element (G-21) in shaping organizational attractiveness, the research team questioned how it is possible to shape the opinions transmitted through WOM. The answers can be found in internal employer branding and company culture that turn employees into company ambassadors. The purpose of this research is not to find out how employees can be transformed into employer-brand ambassadors. Still, the confirmed link between organizational attractiveness and WOM and employer branding and company culture creates a framework for an applied study on the influence of employer branding and company culture on WOM.

DISCUSSION ON THE PRACTICAL IMPLICATIONS

AND CONCLUSIONS

These research propositions induce some practical implications for employer brand management. The first implication is that the HR Department and Marketing and Communication Department should implement the employer-branding process in a joint strategy. When we try to identify EB effects, we list advantages such as a favorable organizational image that attracts better recruitment outcomes, more differentiation, stronger emotional bonds, and financial returns. The results of EB strategies and the relations established by respondents between the attractiveness of a company and various elements included in EB, show that we have two EB approaches: internal EB and external EB, each managed separately by the HR and Marketing departments. But a company’s image and organizational attractiveness imply a holistic, comprehensive perception, so the EB strategy must be coherently thought out and implemented, integrating internal EB (which will generate WOM, for example) and external EB (which will create visibility, differentiation, and so on).

Another practical implication could be a shift in the management perspective on employees. In general, employees are prioritized through company culture and EVP as part of internal employer branding. This study showed the relations between organizational attractiveness, company culture (emphasizing symbolic attributes), and external employer branding. WOM, social and developmental values (which are dimensions of company culture) place employees at the center of the discussion about external employer branding too. So, they are not just the focus of internal EB and company culture strategies. In order to optimize external EB, employees should be considered as strategic assets. Hence, the company’s strategy in regard to positioning, differentiating from the competition, and strengthening organizational attractiveness, should be taking into account employees as resources or strategic assets.

This study sought to clarify the relation between employer branding, organizational attractiveness, and company culture. It highlighted the intersection points between these concepts and how they are associated with the reasoning of stakeholders, IT employees, and representatives of IT companies. To sum up, the article argues that internal employer branding is developed as a contribution to company culture, and company culture (in the form of symbolic attributes) must be communicated through external employer branding to increase organizational attractiveness. This paper was limited to the validation of these points of interaction between the domains. We did not operationalize in detail each concept to find connections and influences in more depth. Being a qualitative study, the findings reveal only the in-depth, mental connections made by representatives of IT companies, industry stakeholders, and IT employees. Therefore, the study has no statistical or quantitative relevance. It only draws attention to a theoretical model of relations between employer branding, organizational attractiveness, and company culture that needs further empirical research.

Although the common areas of these domains were determined, it is still extremely important to conduct a far-reaching and integrative analysis of the current symbolic organizational personality inference to discover precise communalities and higher-order dimensions. This type of approach might point to some common meta-dimensions for EB, organizational attractiveness, and company culture. As symbolic, organizational, personality interpretations indicate social reputation rather than inner cognitions or self-perceptions of behavioral models it is more likely that these higher-order issues will imply central dimensions of social judgment than significant dimensions of human personality.

Most researchers (both recruitment and organizational-culture researchers) have focused on the instrumental and symbolic attributes related to employer image. This paper is also in line with this perspective, referring especially to symbolic attributes. In addition to these two types of attributes, there are also experiential attributes that describe the concrete experiences with the employer through past applications, recruitment events, or other interactions with a specific company. These attributes have received less attention, although they are part of many theories regarding the brand attributes in marketing. To add valuable research on such experiential attributes, recruitment, and organizational culture, scholars could draw on recent marketing advances. For example, researchers should get inspired by brand experience management’s topics and methodologies and apply them to the study of experiential attributes related to company culture or employer branding.

Another conclusion concerns the practical implications of areas such as employer branding and company culture. Although significant advancement has been made in measuring employer image through researchers’ work, there is still a challenge for practitioners to align employer image with its conceptualization. Construct clarity should prevail in developing future measures, both in academic papers and in practitioners’ work. Similarly, measures used in third-party, employer-branding measurements and accreditations (e.g., Best Companies to Work For, Great Places to Work) should be constructed based on the best available data regarding the conceptualization of employer image. For instance, this entails that both instrumental and symbolic attributes should be added to the research and reliably assessed in order to avoid confusion between the reputation, image, and identity of an organization.

References

Aiman-Smith, L., Bauer, T., & Cable, D. (2001). Are you attracted? Do you intend to pursue? A recruiting policy capturing study. Journal of Business and Psychology, 16(2), 219- 237. https:// doi.org/10.1023/A:1011157116322

Ambler, T., & Barrow, S. (1996). The employer brand. Journal of Brand Management, 4(3), 185-206. https://doi.org/10.1057/bm.1996.42

Arachchige, B., & Robertson, A. (2011). Business student perceptions of a preferred employer: A study identifying determinants of employer branding. The IUP Journal of Brand Management, 8(3), 25-46.

Backhaus, K., & Tikoo, S. (2004). Conceptualizing and researching employer branding. Career Development International, 9(5), 501-517. https://doi.org/10.1108/13620430410550754

Berthon, P., Ewing, M., & Hah, L. (2005). Captivating company: Dimensions of attractiveness in employer branding. International Journal of Advertising, 24(2), 151-172.

Biswas, M., & Suar, D. (2014). Antecedents and consequences of employer branding. Journal of Business Ethics, 28(3), 243-253, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2502-3

Breaugh, J., & Starke, M. (2000). Research on employee recruitment: So many studies, so many remaining questions. Journal of Management, 26(3), 405-434. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920630002600303

Cable, D. M., & Turban, D. (2001). Establishing the dimensions, sources and value of job seekers’ employer knowledge during recruitment. Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management, 20, 115-163.

Collins, C., & Kanar, A. (2013). Employer brand equity and recruitment research. In K. Yu & D. Cable (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Recruitment. Oxford: Oxford Library of Psychology.

Collins, C.J., & Stevens, C.K. (2002). The relationship between early recruitment-related activities and the application decisions of new labor-market entrants: A brand equity approach to recruitment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 1121–33.

Davies, G. (2008). Employer branding and its influence on managers. European Journal of Marketing, 42(5/6), 667-681. https://doi.org/10.1108/0309056081086257

Davies, G., Chun, R.,Vinhas da Silva, R., & Roper, S. (2004). A corporate character scale to assess employee and customer views of organization reputation. Corporate Reputation Review, 7, 125-146. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.crr.1540216

DelVecchio, D., Jarvis, C.B., Klink, R.R., & Dineen, B.R. (2007). Leveraging brand equity to attract human capital, Marketing Letters, 18, 149–64.

Desimone, R. L., Werner, J. M., & Harris, D. M. (2002). Human Resource Development (3rd ed.). Orlando, FL: Harcourt College Publishers.

Edwards, M. (2010). An integrative view of employer branding and OB theory. Personnel Review, 39(1), 5-23. http://doi.org.10.1108/004834810011012809

Fernandez-Araoz, C., Groysberg, B., & Noharia, N. (2009). The definite guide to recruiting in good times and bad. Harvard Business Review, 87(5), 74-84.

Gardner, T.M., Erhardt, N.L., & Martin-Rios, C. (2011). Rebranding employment branding: Establishing a new research agenda to explore the attributes, antecedents, and consequences of workers’ employment brand knowledge. Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management, 30, 253–304.

Gatewood, R., Gowan, M., & Lautenschlager, G. (1993). Corporate image, recruitment image and initial job choice decisions. Academy of Management Journal, 36(2), 414-427. https://doi.org/10.2307/256530

Gilliver, S. (2009). Badenoch & Clark guide. Employer Branding Essentials, 4(3), 35-50.

Helm, S. (2013). A matter of reputation and pride: Associations between perceived external reputation, pride in membership, job satisfaction and turnover intentions. British Journal of Management, 24(4), 542–556. https://doi.org.10.1111/j.1467-8551.2012.00827.x

Highhouse, S., Zickar, M.J., Thorsteinson, T.J., Stierwalt, S.L., & Slaughter, J.E. (1999). Assessing company employment image: An example in the fast food industry. Personnel Psychology, 52, 151–72.

Holliday, K. (1997). Putting brands to test. U.S. Banker, 107(12), 58-60.

Jain, N., & Bhatt, P. (2015). Employment preferences of job applicants: Unfolding employer branding determinants. Journal of Management Development, 34(6), 634-652. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMD-09-2013-0106

Keller, K.L. (1993). Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. Journal of Marketing, 57, 1–22.

Kucharska, W., & Kowalczyk, R. (2019). How to achieve sustainability?—Employee’s point of view on company’s culture and CSR practice. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 26(2), 453-467.

Lievens, F. (2007). Employer branding in the Belgian army: The importance of instrumental and symbolic beliefs for potential applicants, actual applicants and military employees. Human Resource Management, 46, 51-69.

Lievens, F., & Highhouse, S. (2003). The relation of instrumental and symbolic attributes to a company’s attractiveness as an employer. Personnel Psychology, 56(1), 75-102. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2003.tb00144.x

Love, L.F., & Singh, P. (2011). Workplace branding: Leveraging human resources management practices for competitive advantage through “Best Employer” surveys. Journal of Business and Psychology, 26(2), 175-181. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-011-9226-5

Nadler, L. (1970). Developing Human Resources. Houston. TX: Gulf Publishing Company

Nelson, D. L., & Quick, J. C. (2011). Understanding Organizational behavior. Belmont, CA: Cengage South-Western.

Otto, P., Chater, N., & Stott, H. (2011). The psychological representation of corporate ‘personality.’ Applied Cognitive Psychology, 25(4), 605-614. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.1729

Pingle, S., & Sharma, A. (2013). External employer attractiveness: A study of management students in India. Journal of Contemporary Management Research, 7(1), 78-95.

Reis, G. G., & Braga, B. M. (2016). Employer attractiveness from a generational perspective: Implications for employer branding. Revista de Administração [RAUSP], 51(1), 103-116. https://doi.org/10.5700/rausp1226

Ryan, G.W., & Bernard, R.H. (2000). Data management and analysis methods. In N.K.

Denzin & Y.S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of Qualitative Research (2nd edition, pp. 769-802). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications

Schien, E.H. (1992). Organizational Culture and Leadership, 2nd Edition. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Sengupta, A., Bamel, U., & Singh, P. (2015). Value proposition framework: Implications for employer branding. Decision, 42(3), 307-323. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40622-015-0097-x

Sivertzen, A., Nilsen, E., & Olafsen, A. (2013). Employer branding: Employer attractiveness and the use of social media, Journal of Product & Brand Management, 22(7), 473-483. http://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-09-2013-0393

Slaughter, J.E., Zickar, M.J., Highhouse, S., & Mohr, D.C. (2004). Personality trait inferences about organizations: Development of a measure and assessment of construct validity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89, 85–103.

Sokro, E. (2012). Impact of employer branding on employee attraction and retention. European Journal of Business and Management, 4(18), 164-173.

Srivastava, P., & Bhatnagar, J. (2010). Employer brand for talent acquisition: An exploration towards its measurement. The Journal of Business Perspective, 14(1-2), 25-34. https://doi.org/10.1777/097226291001400103

Abstrakt

Niniejszy artykuł ma na celu zbadanie zasadności łączenia wysiłków działu HR oraz działu marketingu i komunikacji we wspólnym definiowaniu i wdrażaniu strategii budowania marki pracodawcy. Aby osiągnąć ten cel, zaprojektowano badania jakościowe, które pozwoliły na ustalenie relacji pomiędzy atrakcyjnością pracodawców, atrakcyjnością organizacyjną i kulturą firmy oraz na zidentyfikowanie, w jakim stopniu kultura przedsiębiorstwa może być komunikowana poprzez employer branding. W rezultacie, badanie wyjaśnia: po pierwsze, powiązania między budowaniem marki pracodawcy, atrakcyjnością pracodawcy, kulturą firmy i granicami tych koncepcji. Następnie przedstawia mechanizm oddziaływania employer branding w odniesieniu do atrybutów kultury firmy. Końcowe wnioski z badań dotyczą praktycznych implikacji dotyczących zarządzania marką pracodawcy. Całość opracowania oparto o jakościowe metody badawcze (wywiady pogłębione i grupy fokusowe) zastosowane wobec interesariuszy, pracowników branży IT oraz przedstawicieli firm IT. Następnie zebrane dane jakościowe zostały przetworzone przy zastosowaniu oprogramowania Atlas.ti 8. Uzyskane wyniki wskazują, że kiedy strategie rekrutacyjne działu HR, i odpowiednio strategie employer brandingowe działu marketingu są zwykle rozważane osobno, w rezultacie ich efektywność znacznie spada, a wizerunek pracodawcy nie jest spójny i atrakcyjny. Podsumowując, wyniki badań implikują następujące rozwiązania praktyczne: a) zespoły zarządzające muszą mieć całościowe podejście do budowania marki pracodawcy, atrakcyjności organizacyjnej i kultury firmy; b) employer branding, aby stał się użytecznym narzędziem zatrzymywania i rekrutacji pracowników, musi być zarządzany zarówno przez działy HR, jak i działy marketingu i komunikacji w ramach skoordynowanej i spójnej strategii oraz c) aby employer branding był skuteczny, to potrzeba strategicznego wzmocnienia działu HR, w wyniku czego pracownicy staną się strategicznymi aktywami firmy.

Słowa kluczowe: employer branding, kultura firmy, strategie HR, atrakcyjność pracodawcy

Biographical note

Maria Corina Barbaros, Ph.D., is senior lecturer at the Department of International Relations and European Studies, Faculty of Philosophy, Social and Political Sciences (“Alexandru Ioan Cuza” University of Iasi, Romania). Her main areas of interest and expertise are organizational communication, health communication, crisis communication, public opinion and public agenda. She has been a fellow of the Romanian Academy, Open Society Institute, Milan University and Institut für Publizistik-und Kommunikationswissenschaft, Freie Universität. Her latest book is Political Communication: Constructing the political spectacle and the public agenda. She is also an active member of the European Association for Communication in Healthcare (EACH).

Conflicts of interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Citation (APA Style)

Barbaros, M.C. (2020). Does employer branding beat head hunting? The potential of company culture to increase employer attractiveness. Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Innovation, 16(4), 87-112.

https://doi.org/10.7341/20201643