Aki Harima, Research Assistant, University of Bremen, LEMEX Chair in Small Business & Entrepreneurship, WilhelmHerbst-Str. 5, D-28359 Bremen, Germany, tel.: +49 421 218 66876, e-mail: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Dr. Sivaram Vermuri, Associate Professor of Economics, Charles Darwin University, 21 Kitchener Drive, Darwin NT 0801, Australia, tel.: +61 8 89468835, e-mail: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

Abstract

This paper explores how diasporans achieve business model innovation by using their unique resources. The hypothesis underlying the paper is that the unique backgrounds and resources of the diaspora businesses, due to different sources of information and experiences as well as multiple networks, contributes to business model innovation in a distinctive manner. We investigate the English school market in the Philippines which is established by East Asian diaspora who innovate a business model of conventional English schools. Two case studies were conducted with Japanese diaspora English schools. Their business is analyzed using a business model canvas (Osterwalder & Pigneur, 2010) and contrasted with the conventional business model. The empirical cases show that diaspora businesses use knowledge about their country of origin and engage with country of residence and multiple networks in different locations and constellations to identify unique opportunities, leading to a business model innovation.

Keywords: business model canvas, east Asian diaspora, transnational entrepreneurship, opportunity recognition, mixed embeddedness.

Introduction

In line with the growing internationalization and transnationalization, the number of overall migrants has increased and the role of diasporans has attracted increasing attention from policy makers and researchers. Diasporans are migrants and their descendants who maintain homeland orientation (Safran, 1991). The impact of their business activities on the world economy has become important. When they move from a country to another, they transfer not only human capital, but they create flows of money (Gillespie et al., 1999; Nielsen & Riddle, 2009; Riddle, 2008) and knowledge and technology (Saxenian, 2005; Kapur, 2001; Tung, 2008).

Businesses conducted by diaspora members are unique because of their resources characterized by mixed embeddedness in country of origin (COO) and country of residence (COR) (Kloostermann et al., 1999). Their main resources are diaspora networks (Dutia, 2012; Kuznetsov, 2006) and cognitive diversity which allows them to recognize unique business opportunities. For instance, Chinese diasporans historically establish their trading business through an intensive usage of Chinese transnational diaspora networks (Cohen, 2008; Cheung, 2004; Rauch & Trindade, 2002). Knowing multiple cultural contexts, diasporans recognize business chances which are not recognized by local population. Turkish diasporans in Europe developed wellknown ‘Döner Kebab’, a fast food they modified for European customers (Wahlbeck, 2004). Indian diasporans identified a number of opportunities in IT industries in their COO (Chacko, 2007).

While the uniqueness of diaspora business and its innovativeness is still relatively unknown, there is a general perception that diaspora business is unique compared to the non-diaspora business. It is therefore important to understand and examine the reasons for this uniqueness. In this paper, we take a closer look at business models in order to investigate the innovativeness and novelty of diaspora businesses.

There are two main reasons for this investigation. First, business models describe not only firms per se, but also interrelations between firms and partners and value co-creation. Diasporans are known to have complex network dynamics due to their mixed embeddedness in host and home countries (Kloostermann et al., 1999). Diaspora networks (Dutia, 2012; Kuznetsov, 2006) are categorized as network resources. Observing their business model enables us to analyze the impact of such network dynamics on their business. Second, business models consist of different components of businesses, which enables us to focus on the impact of diaspora resources on each of components separately.

The aim of this paper is to address the following research questions: (i) How do diasporans innovate an existing business model? (ii) How do they use their diaspora resource for business model innovation? In order to answer these questions, we investigate the English language school industry in the Philippines, which is established by East Asian diasporans. They created a business model innovation (Chesbrough, 2010; Chesbrough & Rosenbloom, 2002) in the English learning market for East Asians by establishing a new business model. This paper investigates their business model compared to the business model of conventional English schools by applying business model canvas (Osterwalder & Pigneur, 2010) as an analytical tool. Two case studies with Japanese English schools in the Philippines as well as extensive secondary data analysis are conducted. This paper will contribute to explore the characteristics of diaspora businesses and the role of resources and embeddedness of entrepreneurs on business model innovation.

This paper is structured as follows: First, previous findings on diaspora business and business model innovation are presented and the usage of business model canvas is introduced as an analytical tool for this study. Subsequently, research approach is described and justified followed by a brief introduction of the diaspora English school market in the Philippines. The brief background provides a context for conducting an analysis of the business models of two different types of English schools. This is followed by a discussion of how diaspora resources influence business model innovation. Finally, together with the summary of research results, contributions as well as limitations are presented.

Conceptual background

Diaspora business

Migration is a growing phenomenon. According to the International Migration Outlook from OECD (2013), there are 232 million people living outside their country of birth around the world in 2013, which represents 3.2 percent of the world’s population. This number is expected to become 405 million by 2050 in the world (International Organization for Migration, 2014). The diaspora can be understood as a specific type of migrants and refers to migrants and their descendants who maintain a strong relationship with their COO and COR (Safran, 1991). These people are in a special constellation of being embedded in multiple cultures and societies of different countries (Drori et al., 2009). This multiple societal and cultural embeddedness is named as ‘mixed embeddedness’ by Kloostermann et al. (1999).

The diaspora population has gained an increasing attention from policy makers and researchers, assisted by the wave of transnationalism, globalization, and accelerated by rapid technological development in transportation and communication, which has reduced migrants’ barriers of maintaining strong connection to home countries (Levitt, 2001; Tölölyan, 1996). Diasporans engage in business activities in a unique form due to their mixed embeddedness and transnational settings. Their business activities have unignorably significant impacts on the global economy. For instance, they send a substantial part of their earnings in COR to their home country in the form of remittance. The total remittance flow was projected to reach 434 billion USD (Worldbank, 2014:3) and diaspora remittance sometimes is an essential financial resource of developing countries. Their business activities, however, do not only have financial impacts on their COO. In fact, they create different types of flows, by transferring knowledge, innovation, technology and institutions (Saxenian, 2005; Riddle & Brinkerhoff, 2011).

Despite its growing importance, the nature and characteristics of diaspora business is still not fully investigated. Previous scholars have attempted to investigate this phenomenon from a rather macro perspective including the impact of ethnic business on the local economy such as job creation and economic and cultural integration (Geddes, 2001; Zabin & Hughes, 1995) or technological diffusion (Saxenian, 2005; Lodigiani, 2009; Hornung, 2014), for instance, through diaspora homeland investment (Gillespie et al., 1999; Kotabe et al., 2013; Nielsen & Riddle, 2009). But we still know little about Diaspora business per se at the micro level. How does their business structure differ from non-diaspora business? Are there any novelties of diaspora businesses compared to non-diaspora businesses? Where are these differences come from? While a detail observation of Diaspora business is still a long way away, there are previous findings that may offer some hints for answering these questions.

Diaspora businesses exist when individuals in the diaspora create them. Diaspora businesses occur because of multiple forms of displacements. The first form of displacement arises from the place of birth resulting in movements from COO to COR. In certain circumstances the conditions in the COR create another form of displacement. It is the second form of displacement which arises from the general workforce and the response to this displacement is where the migrants search for connections elsewhere such as the one where migrants are attracted to business as they are not able to function in the mainstream economic activities of the COR. A third form of displacement occurs when diasporans in businesses at the COR become business diasporans in both COO and COR. The market conditions in the COR create an environment for opportunity seeking for building on connections elsewhere resulting in being attracted to familiar to familiar factors in COO. Diaporans become enablers of business operations, and market expansions. Thus businesses undergo triple transformations unlike the non-Diaspora businesses (Vemuri, 2015). As a result, diaspora business is an embodiment of continuous innovations and needs a closer examination to understand business innovations. There are differentiating features of emergent diaspora businesses that are primarily based on the experiences of individuals belonging to the diaspora such as pull, push, re-pull, and repush factors associated with migration (Vemuri, 2014). At one level, the displacement and reconnection to spaces through time is an essential reason for the existence of diaspora businesses. At another level, their nature of existence is due to discontinuity from the organic and endogenously evolving organizational skin. Therefore, diaspora businesses exist combining both business and diaspora features.

Business model and innovation

A business model describes the way value is created within an organization by focusing on various components of firms’ activities and their interrelations. A business model, therefore, becomes a frequently-used unit of analysis for researchers, warranting a need to understand a holistic overview of creation of total value. Recently business models have attracted much attention from both academicians and practitioners. According to the literature review by Zott et al. (2011), peer-reviewed academic journals published at least, 1,777 articles on business models have been published. In a similar vein, Ghaziani and Ventresca (2005) found 1,729 publications that referred to the term ‘business model’.

One of the main explanation for the growing interest on business models is that a business model can create a new form of innovation, which possibly create more sustainable competitive advantages than other forms of innovation (Chesbrough, 2007). A business model innovation can be realized either by existing firms, which innovate or change their original business model, or by new entrants, which implement a new business model to the market. Business model requires simultaneous change to two or more elements of a business model to recreate and convey value in a novel way (Lindgardt et al., 2009). According to Bucherer et al. (2012), there are two main reasons why business model innovations create competitive advantages. First, it takes considerable time and resource investment for simultaneously changing different elements. For instance, when a firm innovates solely an existing product such as application of new technology to a digital camera or smartphones, competitors imitate with relative ease, because firms do not have to change their entire business model. However, when a business model itself is innovated like IKEA, the Swedish furniture company which innovated different components of business models of the conventional furniture retailers including value propositions, customer segments, customer channels, it is more challenging for existing furniture retailers, as they have to change many of their business components at the same time. Second, the new business model should suit all facets of the company including longterm corporate strategy, corporate culture as well as core competencies of the firm. Using the example of IKEA, imitating IKEA’s business model is almost impossible when furniture retailers focus on luxurious customer segments, have traditional corporate cultures, or rely strongly on long-standing partners over generations who have developed routines and practices, and become reticent to fundamentally change their business model.

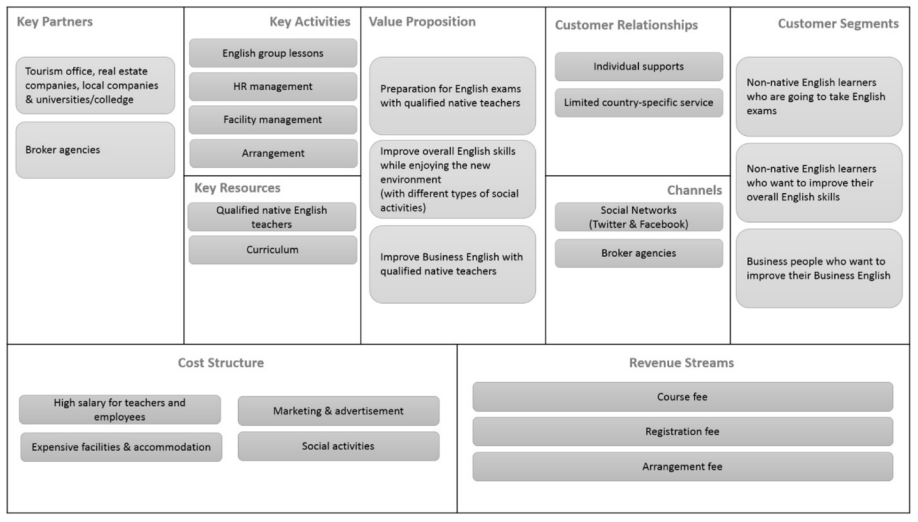

In either case, a precursor to business model innovation by firms is their need for tools to assess their current business model or dominant business model in the market in order to create new ones. While there are a number of tools with different components developed by various scholars (c.f. Morris et al. 2005), one of the most famous and detailed analytical tool is the business model canvas (Osterwalder & Pigneur, 2010). It allows companies to actively create and assess new or already existing business models (Pavie et al., 2013). Business model canvas consists of nine interrelated components: (1) customer segments, (2) value propositions, (3) channels, (4) customer relationships, (5) key activities, (6) key resources, (7) key partners, (8) revenue streams, and (9) cost structure. This analytical tool has an advantage of simultaneously visualizing many factors and their interrelations.

Diaspora business model innovation

Diaspora businesses are unique. In some cases, this uniqueness is because of the nature of the business model innovation undertaken by the diaporans. Which role does diaspora play in creating an innovative business model? In this section, we discuss the possible role of diaspora in business model innovation. In the context of this paper, we consider diaspora business model innovation to occur when diasporans simultaneously change more than two components of existing business models in a novel way, following the definition by Lindgardt et al. (2009).

As discussed above, diasporans are characterized by their mixed embeddedness in different country contexts (Kloostermann et al., 1999). We suggest that mixed embeddedness enables diasporans perceiving unique opportunity, which then leads to business model innovation. Ardichvil et al. (2003) provide a framework of opportunity identification by arguing that beside personality traits, prior knowledge and social networks influence entrepreneurial alertness. Entrepreneurial alertness is defined as ‘a propensity to notice and be sensitive to information about objects, incidents, and patterns of behaviors in the environment, with special sensitivity to maker and user problems, unmet needs and interests, and novel combinations of resources’ (Ray & Cardozo, 1996). The higher alertness increases the likelihood of an opportunity for being recognized. Diasporans’ experiences, accumulated knowledge and network capital are assumed to be positively related to unique opportunity recognition.

How can diasporans’ mixed embeddedness leads to unique business opportunity recognition? First, through being embedded in two or more different country contexts, diasporans accumulate diversified knowledge based on first hand exposures and experiences of both countries. Prior knowledge can be industry knowledge such as knowledge of markets, customer problems and ways to serve customers (Ardichvili et al., 2003; Shane, 2000; Baron, 2006; Hoang & Antoncic, 2003). Diaspora population is assumed to have profound knowledge about markets and customers of COR and COO. Knowing different markets and customer problems and characteristics of two countries are assumed to increase entrepreneurial alertness, and therefore enable them to recognize unique business opportunity which is otherwise overlooked by local population. This can lead them to innovate different components of their business model. As diasporans know markets of both COO and COR, they could, for instance, choose their customer segments from COO or COR, or both. In a sense, they have a larger base and variety to select from. They could also reflect their knowledge about customer problems and ways to serve customers of COO and COR on customer relationships, value propositionand channels. They are assumed to be able to change an existing business model in COR, which targets at customers in COR, into a new business model in COR, which targest at customers in COO, or other way around.

Second, business activities of diasporans are also characterized by their unique network dynamics. Especially, the so-called ‘diaspora network’, which describes their network with co-ethnics in COO, COR and other countries, has attracted considerable research attention as one of the most unique part of their network dynamics (Dutia, 2012; Meyer & Wallaux, 2006; Kurnetsov, 2006; Elo, 2014). Diaspora network is known as a source of labor (Damm, 2009) as well as customers (Bowles & Herbert, 2004; Anthias, 2007) for diaspora businesses. Harima (2014) also argued that a diaspora network offers various benefits such as acquisition of external resources and sustaining motivation. Having a network not only with the local population, but also with co-ethnics living in different countries is assumed to be positively related to entrepreneurial alertness. Such networks can offer key partnersor key resources. Diasporans can choose their business partners from different networks. They can be someone from COO or COR, or even somewhere else, where co-ethnics are living. As diaspora networks often offer labors, diaspora may have different human resource bases to draw from than Non-Diaspora business.

To sum up, diasporans’ mixed embeddedness allows them to innovate different components of business models in unconventional ways, as they can identify unique business opportunities which are overlooked by local population in COR. We suggest that diasporans’ knowledge of customers and markets, factor markets in particular, in COO and COR impacting on their to network dynamics to such an extent that they allow them to identify opportunities to innovate an exisiting business model.

Research methods

The aim of this study is to answer the following research questions: (i) How do diasporans innovate an existing business model? (ii) How do they use their diaspora resources for business model innovation? In order to answer these questions, we chose the English school industry in the Philippines. This industry was established by the East Asian diaspora, who innovated a business model of conventional English schools for non-native English learners. These English schools in the Philippines are established mostly by South Korean or Japanese diasporans and targeted at their co-ethnic customers who visit the Philippines to learn English. They employ and train Filipino English teachers.

Two case studies were conducted with the Japanese Diaspora English schools (‘School A’ & ‘School B’) in the Philippines. We chose a case study approach design, as it should be considered to answer “how” questions according to Yin (2003). She also pointed out that a case study approach can cover contextual factors which are relevant to the phenomenon. As diasporans’ unique constellation is a central focus of this study, this approach is chosen. Unit of analysis is the individual diaspora entrepreneurs who reflect their diaspora resource on business model components. In order to explore how diasporans innovated a business model of conventional English schools in Western English speaking countries, their business models are also investigated. For the sake of simplification, we call the English schools in the Philippines ran by East Asian diaspora as “diaspora English school” and the other “conventional English school” in this paper.

Within the scope of the case studies, the main data is in-depth interviews with Japanese founders. In-depth interviews took 60 – 180 minutes and were conducted in Japanese. Additionally, a number of casual conversations were conducted with Japanese employees, Filipino management employees, Filipino teachers and Japanese customers on the location. In April 2015, one of the authors stayed three days at the School A and one day at the School B, which allowed her ethnographical observation (Tedlock, 1991). Memos taken during the observation as well as company websites are used for data triangulation (Denzin, 1970). As for Conventional English Schools, we gathered secondary data including official websites, web reputation as well as brochure of five English schools in USA, Canada, UK, Australia and New Zealand. The summary of data collected is described in Table 1.

We selected these two schools, since School A is a pioneer and one of the first English schools established by Japanese diasporans in the Philippines, and School B is a late-comer. Taking a closer look at these two schools allows us to consider variations caused by market entry timing. We selected five conventional English schools in five Western English speaking countries, which are main destinations of East Asian English learners, based on the popularity according to agents.

| Interview partner | Style | Type of Interaction | Duration (min.) | Language | Data | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| School A | Japanese founder | Skype | Interview | 120 | Japanese | Recorded and transcribed |

| Japanese founder | Skype | Interview | 80 | Japanese | Recorded and transcribed | |

| Japanese founder | Face-to-face | Conversation | 240 | Japanese | Interview memo | |

| Japanese employee A | Face-to-face | Conversation | 60 | Japanese | Interview memo | |

| Japanese employee B | Face-to-face | Conversation | 10 | Japanese | Interview memo | |

| Japanese employee C | Face-to-face | Conversation | 10 | Japanese | Interview memo | |

| Japanese employee D | Face-to-face | Conversation | 10 | Japanese | Interview memo | |

| Japanese employee E | Face-to-face | Conversation | 60 | Japanese | Interview memo | |

| Filipino teacher A | Face-to-face | Conversation | 25 | English | Interview memo | |

| Filipino teacher B | Face-to-face | Conversation | 25 | English | Interview memo | |

| Filipino teacher C | Face-to-face | Conversation | 10 | English | Interview memo | |

| Filipino teacher D | Face-to-face | Conversation | 20 | English | Interview memo | |

| Filipino teacher E | Face-to-face | Conversation | 15 | English | Interview memo | |

| Japanese customer A | Face-to-face | Conversation | 180 | Japanese | Interview memo | |

| Japanese customer B | Face-to-face | Conversation | 60 | Japanese | Interview memo | |

| Japanese customer C | Face-to-face | Conversation | 60 | Japanese | Interview memo | |

| School B | Japanese founder A | Skype | Interview | 70 | Japanese | Recorded and transcribed |

| Japnesemanager | Skype | Interview | 60 | Japanese | Recorded and transcribed | |

| Filipino director | Face-to-face | Interview | 70 | English | Recorded and transcribed | |

| Jpanese director | Face-to-face | Conversation | 60 | Japanese | Interview memo | |

| Filipino manager | Face-to-face | Conversation | 40 | English | Interview memo | |

| Filipino teacher | Face-to-face | Conversation | 5 | English | Interview memo |

Gathered information and data through above mentioned methods are analyzed in a descriptive manner. As an analytical tool, business model canvas (Osterwalder & Pigneur, 2010) is used, which helps us to visualize business models of diaspora English schools and conventional English schools.

English language market in the Philippines

Being a past colony of the United States, the Philippines has the fifth largest English-speaking communities by population in the world. According to Census 2000, there were 45.9 million English speakers, which represents 63.7% of the entire population of the country. Based on this fact, the country has attracted foreign investment employing low-cost English speaking Filipino staff. Since the late 1990s, a number of American firms started outsourcing telephone-based customer services to Filipino professionals (Friginal, 2007). Shortly after, South Korean firms opened up a language business in the Philippines and followed by the Japanese. While the exact number of such schools is unknown, the widely used number of such East Asian English schools in the Philippines is between 300 and 500. The industry has steadily grown over the last years. According to the Department of Tourism in the Philippines (2003; 2013), from 70,000 to 100,000 foreign people visit the country as English language students annually. The country became one of the major destinations for South Korean and Japanese people who want to learn English abroad instead of Western English speaking countries. This emergent market represents the case in which diasporans created a new market through business model innovation. Next, we will analyze business models of such diaspora English schools and contrast them with conventional English schools.

Business model canvas

In order to investigate how diasporans innovated an existing business model, we first briefly analyze nine components – (1) customer segments, (2) value propositions, (3) customer relationships, (4) channels, (5) revenue streams, (6) key activities, (7) key resources, (8) key partners, and (9) cost structures – of business model canvas of conventional English schools based on the secondary data. This will be followed by an analysis of the business models of diaspora English schools in the Philippines.

Conventional English schools

- Customer Segments: Customer segments can be described with the following four dimensions: (i) nationality, (ii) age, (iii) purpose of visit, and (iv) duration of visit. First, these schools do not target at specific nationalities, but at every non-native English learners. Second, they mainly target at the people older than 16-18 years old and do not commonly offer any special courses for children. Third, customers of conventional English schools have the following purposes of visit: (a) Exam preparation such as TOEFL, IELTS and TOEIC 3 ; (b) Improvement of conversational English, (c) improvement of business English. Fourth, these schools target mostly at long-stay students for one to twelve months. Based on this information, the typical customer segments of conventional English schools can be described as follows: (1) Non-native English speakers who want to prepare for English exams, (2) Non-native English speakers who want to improve their English conversational skills, and (3) Business personals who want to improve their business English.

- Value Propositions: They have value propositions for each of three customer segments respectively: (1) Improve customers’ English skills for reaching a high score at English exams with the support of qualified native English teachers; (2) Improve customers’ English conversational skills with the support of qualified native English teachers; and (3) Improve customers’ business English skills with the support of qualified native English teachers.

- Customer Relationships: Local staffs take care of them during their stay by giving them personal advice and finding temporary accommodation, organizing social activities as well as vocational opportunities (e.g. internship) with costs. Some schools have staffs who are able to speak the language of the dominant student groups such as Chinese, Japanese, and Spanish.

- Channels: They reach their potential customers mainly through Internet websites/advertisement as well as through broker agents in different countries.

- Revenue Stream: It consists of a registration fee, organizational fee and course fee. While the price varies between countries and cities, a student, for instance, would pay ca. 2,200 USD for 20 hours of English lessons for four weeks in a large city in Canada excluding accommodation fee.

- Key Activities: Conventional English schools have two main activities. The first activity is offering different types of English lessons/courses. These courses are oriented mainly towards groups. In order to ensure the quality of lessons, training teachers, controlling and improving lessons are included in key activities as well. The second activity is organizing accommodation, social activities and internships.

- Key Resources: In order to conduct the above-mentioned key activities, these schools have qualified native English teachers and original curriculum to satisfy customers’ needs.

- Key Partners: They have partnerships with broker agents in different countries, tourism offices, real estate companies, local firms, local host families, and universities/colleges in their country and abroad.

- Cost structures: Considering the eight components above, they have the following costs: salaries of teachers and local staffs, facilities costs as well as marketing cost which they usually pay to brokers. These costs are considered to be high, as conventional English schools are located in developed countries with a high living standard. The business model of Conventional English Schools is depicted in Figure 1.

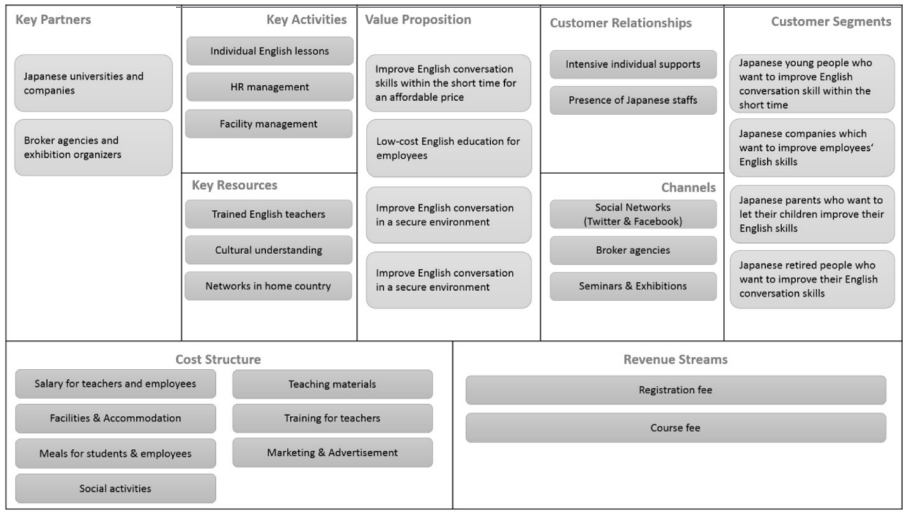

Philippines, we analyze a business model of diaspora English schools with the help of business model canvas. School A was established in 2010 by a Japanese founder together with a Filipino co-founder in San Manuel. Since the establishment, this school has been successfully operating its language business and more than 2,000 students have learned at the school. This school has become one of the largest employers in the region. School B is a part of a large group established by Japanese founder. He started his business activities in the Philippines in 1989. Starting with trading business, he has continuously expanded his business to manufacturing, manpower supply, health service; his group has currently twelve companies in the Philippines and in Japan. He started his language business in 2005 by offering Japanese language course for Filipinos and then offering English online to Japanese customers. His English schools is established in 2015 in Manila and starts offering English school service for Japanese customers. Both of the schools have more than 20 full-time English teachers.

Diaspora English schools in the Philippines

- Customer Segments: Analyzing the same four dimensions as conventional English schools, (i) nationality, (ii) age, (iii) purpose of the visit, and (iv) duration of the visit, we confirmed that Diaspora English Schools are more specific in every dimension. First, these schools generally focus on the customers with the same country of origin as school owners. According to the founder of School A, “…(our customers are) mostly Japanese. More than 90% are Japanese and the others are Korean.” The manager of the School B also indicates that this school targets only at Japanese customers and does not have any intention to target at other nationalities. The reason for this clear customer segmentation is explained by the founder of School A as follows: “Japanese customers have special demands which cannot be fulfilled by Korean schools. We offer breakfast, lunch and dinner for our customers. We can offer meals which are preferred by Japanese customers. Korean customers eat very spicy food every day, but Japanese not. Korean customers prefer strict and a sort of military style rules at schools, Japanese want to learn English also in an intensive manner, but rules and curriculums should not be as tough as Korean schools. Japanese customers are very shy, we need to train our Filipino teachers to understand characteristics of Japanese customers. We can offer service and staff support which exactly match their expectation, as we understand their unique demand.”

Second, diaspora English schools target at different age groups. While the main target is university students and young professionals who want to improve their English for their career, School A also targets at children up to twelve years old as well as senior people. The case of School A shows that the founder’s awareness of Japanese culture and society was essential for this customer segmentations: “University students have much time in Japan but do not have much money. They could but afford learning English in the Philippines because it is much cheaper than in USA or Australia. Business people are sent by companies, who are not happy with long absence of their employees. They want their employees to learn English as quick as possible, like one or two weeks. Curriculums of conventional English schools are oriented at people who want to stay for a longer term and therefore they do not have an extremely intensive course. At our schools, they can take lessons more than nine hours a day. After the lessons, we have enough rooms for them to study alone. For children, parents want them to go abroad at the early stage, but they don’t want them to travel far away. The Philippines is still closer to Japan than other Western English speaking countries. Travelling to the Philippines is easier due to short flight hours and only one hour of time difference between the two countries. Moreover, Japanese parents want to send their children to schools where Japanese staffs are working. Senior people have a sort of similar situations. They do not prefer to take a long flight to Australia or to USA, UK. They also prefer nice tropical weather and customer supports by Japanese staffs.” School B, in contrast, is not fully sure with its target group. The manager of School B explains the strategy of school as follows. “Well, we are targeting at business people who have enough money, because we offer high-quality service. Therefore, we do not offer apartments but business hotels as accommodation. Maybe we also target at university students and senior people who have enough money.”

Third, these schools also focus on the customer segments whose purpose of visit is to learn conversational English. Due to the inefficient education system overemphasizing on written exams, inactive student participation during the class and cultural differences (for instance, Japanese students are ashamed of making grammatical mistakes in front of others), South Korean and Japanese people have extreme difficulty in communicating in English (Dougil, 2008). Both School A and School B are aware of communication problems of Japanese customers and structure their program to minimize them.

Fourth, both School A and School B mainly target at people who intend to stay abroad for a short time, because they are aware that Japanese customers are not able to leave their country for a long time. Japanese students are under the pressure of ‘simultaneous recruiting system’ (Amin, 2012), which refers to the custom that companies hire new graduates all at once and employ them during the third of four years of bachelor studies, and Japanese employees take only 10 work days off annually (Ray et al., 2013).

Considering the points described above, diaspora English schools target at the following customer segments: (1) Young Japanese students and career changers who want to improve English within the relatively short time by focusing on conversational English; (2) Japanese firms who want to improve English skills of their employees within the limited budget and time; (3) Japanese parents who want to let their children improve their English skills; (4) Japanese retirees who want to improve their English conversational skills. - Value Propositions: For each of four customer segments, diaspora English schools have value propositions: (i) Learn how to communicate in English intensively within the short term at an affordable price; (ii) Improve employee’s English skills within the short term at low budget; (iii) Improve children’s English skills in a secure environment; (iv) Learn English in a secure and comfortable environment. One of the characteristics of diaspora English schools is that they offer one-to-one lessons. The founder of School A recalled his own experience in learning English in USA and said, “I think almost all of the Japanese have the same problem as I had in the United States, when I was a language student. You pay much money for English group lessons and attend them to end up speaking just one sentence during 4 hours of class. Japanese people are very shy. Even though they have a better grammatical understanding than European people, European students speak much more, because their mother tongue is similar to English and their education system focuses also on communication unlike in Japan. I thought, one-to-one lessons are the only way for Japanese to improve English.”

- Customer Relationships: School A has a very close relationship with customers, as the founder, all of the Japanese staffs and most of Filipino English teachers live together on the same campus. School B has more distance from customers, but Japanese staffs both in Japan and in the Philippines can take care of their customers before and during their stay.

- Channels: School A uses Internet websites as well as social networks such as Twitter and Facebook as channels to reach their customers. School B does direct marketing to their customers of Online English schools. School B has offered Online English schools in the final years and they have a large pool of customers. While there are also seminars and exhibitions for English schools in the Philippines, both of them did not use such external agents.

- Revenue Streams: Similar to conventional English schools, the main revenue stream of diaspora English schools is the course fee. The noticeable difference is that the course fee often includes accommodation fee and meals at diaspora English schools. For example, the lowest price at School A for one week is 264 USD4 with 20 hours of one-to-one lessons, five hours of group lessons, meals (breakfast, lunch, and dinner), as well as accommodation in a shared room with four people. Depending on room types and hours of lessons, this price varies. Even with the fee for accommodation and meals, the price is significantly cheaper than Conventional English Schools.

- Key Activities: Similar to conventional English schools, their key activity is offering English lessons/courses. While conventional schools mainly offer group lessons, diaspora English schools offer almost exclusively one-toone English lessons. Additionally, they also manage accommodation, facilities for students and employees as well as social activities. School A has also special rooms for customers to learn English after lessons until midnight. The founder of the School A explained that “Japanese customers are used to the ‘Jisyushitsu (自習室 )5’-culture. Since they have to learn a lot for cram schools, for university entry exams and so on.” In fact, these rooms were all booked until midnight when one of the authors visited the school. It shows that this facility fulfills customers’ unique demands. School B also facilitates access to a room with electronic devices which allow students to practice English pronunciation. The local Filipino director of School B explains, “Japanese people have difficulties to pronounce English, as there are not many English teachers who can do that in Japan. Therefore, we developed this room, as we focus on conversational English.”

- Key Resources: In order to conduct the above mentioned activities, diaspora English schools are required to orchestrate local resources and diaspora resources. It is essential for them to successfully train Filipino English teachers to be able to understand the demand and characteristics of Japanese customers. “We trained our English teachers to be able to understand problems and difficulties of Japanese customers. (…) frequently we ask our students and teachers which problems they face in order to continuously improve our service. We should understand both Japanese customers and characteristics and culture of Filipino English teachers.” (School A’s founder). It is a complex task to train people from different cultural backgrounds, as founders and managers are required to have deep understanding of both cultures and successfully combine them. Their own understanding and awareness of Japanese society and culture is also related to customer satisfactions.

- Key Partners: Diaspora English schools have a partnership with Japanese corporate customers and Japanese universities. They also collaborate with some local firms such as tourism office, transportation firms and hotels. School A has also a number of partnerships with Japanese companies in different countries of South East Asia. As some of Japanese students are interested in starting their career abroad after improving their English at Diaspora English schools, school A introduced students to these firms. In this case, Japanese diaspora network within South East Asian countries plays an important role.

- Cost Structure: In the case of diaspora English schools, the following costs: salary for Filipino English teachers, local employees and Japanese staffs account for a large part of their cost structure. Compared to conventional English schools, however, the salary for English teachers and local staff is considerably low, as the average salary in the Philippines is lower than the other Western English speaking countries. According to the International Labor Organization (2009), the monthly average wage in purchasing power parity dollars in the Philippines is 279 USD. Filipino English teachers earn more than the average and have more support from Japanese employers in both cases. The cost for facilities such as school buildings as well as accommodation is also a major cost component. The business model canvas of diaspora English schools is depicted in the Figure 2.

Discussion

The above depicted business model canvas clearly show that a business model innovation took place in the English School market in Philippines. While all of the nine components of business model canvas of the conventional English schools were changed to a certain extent, the East Asian Diaspora innovated mainly five components in a novel way: (i) customer segments; (ii) value propositions; (iii) key resources; (iv) key partners; and (v) cost structures.

First, diaspora English Schools target at customers from their COO and segmentzed them into four groups to fulfill their unique demands. This customer segmentation is reflected on their value propositions. These schools consider specific demands and expectations of each of customer segments to develop their value propositions. As for key resourcesof diaspora English schools, they are required to orchestrate their COO-resources and CORresources by training Filipino English teachers to offer service which fulfill needs specific to Japanese customers. In a similar vein, diaspora English schools have a partnership with organizations both in COO and COR. At last, they add more values such as accommodations, meals or individual lessons by reducing cost for English teachers.

In the section of ‘Diaspora Business Model Innovation’, we discuss our assumption that diasporans’ mixed embeddedness may positively influence their unique opportunity recognition, because they have knowledge about customers and markets in both COO and COR as well as country specific network dynamics. Following, we analyze how the mixed embeddedness influence the business model innovation by East Asian diasporans in the Philippines by contrasting two Business Model Canvases (Figure 1 & 2).

First, both of the cases vividly show the significance of knowledge about COO and COR. In case of School A, the founder uses his knowledge of Japanese society, job market as well as customer demands to identify unique customer segmentsand develop value propositions. It was his initial entrepreneurial motivation to solve the problem that Japanese cannot learn English effectively at Conventional English Schools despite of their large investment because of their shyness and Japanese English education which overemphasizes English grammar. He combined this knowledge into his knowledge about COR, as he also knew that what Philippines can offer for his business idea. In School B’s case, School B was forced to segmentalize customers, as School B is a follower. Although School B’s entrepreneur has more than 30 years of experience in the Philippines, he was new to the English School industry, which was already fully established with 300-500 diaspora English Schools. In order to avoid the fierce competition, School B decided to focus on the luxury segment. The entrepreneur’s knowledge about the Philippines and Japan help the School B to offer luxurious service to Japanese business customers.

The knowledge about culture and society of COO and COR was also essential for the key resourcesof diaspora English schools. Their key resource is trained Filipino English teachers. In order to train Filipino English teachers to be able to understand Japanese customers’ demand, they need to understand the culture and society of both countries.

How did their unique network dynamics influence opportunity recognitions to innovate an existing business model of conventional English schools? Figure 2 indicates that diaspora Business schools leverage different networks for their key partnership. Their customers, agents, staffs are Japanese, while other local staffs, English teachers, and some of their business partners are Filipino. They also have some partnerships with Japanese firms and universities in Japan whose employees/students visit schools to learn English. In case of School A, the school has also a broad diaspora network with Japanese firms in different countries in South East Asia who are interested in hiring Japanese students. In fact, many of alumni started working for these companies after leaving School A.

As for cost structure, mixed embeddedness did not play any significant role in terms of opportunity recognition. Using a low-cost labor in developing/ emerging countries for the benefit of own business is common also for companies from developed countries and is not specific to diaspora business.

In conclusion, our empirical cases show how East Asian diasporans leverage their mixed embeddedness to identify unique opportunities which lead them to innovate a conventional business model. Not only knowing contexts and markets of COO and COR, but also how they combine and orchestrate their knowledge to identify unique customer segments and develop value propositionsas well as key resources. They also use different types of networks in COO and COR, and diaspora networks even in other countries as key partnersfor their business model.

Conclusion

This paper explores how diasporans innovate an existing business model, and how they use their diaspora resources for business model innovation. In order to answer these questions, we take a closer look at the English school industry in the Philippines, where East Asian diasporans achieved a business model innovation. Thereby, we focus on their mixed embeddedness and its impact on unique opportunity recognition. Through conducting the two case studies with Japanese diaspora English schools, we developed business model canvases (Osterwalder & Pigneur, 2010) of Diaspora English Schools and Conventional English Schools to investigate how diasporans innovated which components, and in which way. The findings show that East Asian diasporans changed mainly five out of nine components: (i) customer segments; (ii) value propositions; (iii) key resources; (iv) key partners; and (v) cost structures. Diasporans’ mix embeddedness allows them to develop knowledge about COO and COR as well as complex network dynamics in different countries. These knowledge and networks allow them to recognize unique opportunities to innovate a conventional business model.

This paper has a few limitations. First, although two insightful case studies of Japanese English schools give us profound insights of Diaspora English Schools, more case studies should be conducted for providing a comprehensive understanding of the industry. For instance, both School A and School B did not have any significant networks with other diaspora English schools or broker agents. Therefore, we could not observe horizontal relationship between numerous diaspora English schools in the Philippines. Second, our analysis is based on one specific market and one specific diaspora. Therefore, this paper could not consider industrial and country variations. Third, while we use business model canvas as an analytical tool, we should be aware of its limitation. For instance, Coes (2014) point out some limitations of business model canvas including missing competitiveness, time elements and social values.

Despite these limitations, this study makes some contributions: First, the role of diaspora in business model innovation was explored by investigating how diasporans use their resources which are a result of mixed embeddedness due to unique opportunities available to them. Diasporans are no longer considered as helpless individuals with limited opportunities. On the contrary individuals being diasporans have expanded opportunities. Second, this study sheds a spotlight on diasporans from developed countries in emerging countries. Since current discussions on diaspora business and entrepreneurship overemphasis on diasporans from developing/emerging countries in developed countries, their business activities give a new insight into the research on diaspora business and entrepreneurship. Third, this paper has also a methodological contribution, showing a business model to be an effective analytical tool for investigating diaspora businesses. Fourth, this research makes a contribution to the business model literature by considering transnational dimensions in the context of business innovation.

Considering the limitations of our study above, we suggest that future research is needed to investigate the role of diaspora in the other country contexts. Moreover, their role in each of stages of firm’s development must be studied. We suggest a use of longitudinal analysis as a meaningful way forward to analyze the role of diasporas for business model transformations overtime.

References

- Amin, H. (2012). Japanese Shinsotsu recruitment culture. Retrieved from http://www.disc.co.jp/en/resource/pdf/SHINSOTSUCulture.pdf (Accessed on 10th of March, 2015).

- Anthias, F. (2007). Ethnic ties: Social capital and the question of mobilisability. The Sociological Review, 55(4), 788-805.

- Ardichvili, A., Cardozo, R., & Ray S. (2003). A theory of entrepreneurial opportunity identification and development. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(1), 105–123.

- Baron, R. A. (2008). Opportunity recognition as pattern recognition: How entrepreneurs “Connect the dots” to identify new business opportunities. The Academy of Management Perspectives, 20(1), 104-119.

- Bowles, S., & Gintis, H. (2004). Persistent parochialism: Trust and exclusion in ethnic networks. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 55(1), 1-23.

- Bucherer, E., Uli E., & Oliver G. (2012). Towards systematic business model innovation: lessons from product innovation management. Creativity and Innovation Management, 21(2), 183-198.

- Chacko, E. (2007). From brain drain to brain gain: reverse migration to Bangalore and Hyderabad, India’s globalizing high tech cities. Geo Journal, 68(2-3), 131-140.

- Cheung, G. C. K. (2004). Chinese Diaspora as a virtual nation: interactive roles between economic and social capital, Political studies, 52(4), 664-684.

- Chesbrough, H. (2007). Business model innovation: it's not just about technology anymore. Strategy & Leadership, 35(6), 12–17.

- Chesbrough, H. (2010). Business model innovation: opportunities and barriers. Long Range Planning, 43(2-3), 354–363.

- Chesbrough, H., & Rosenbloom, R. S. (2002). The role of the business model in capturing value from innovation: evidence from Xerox Corporation's technology spin-off companies. Industrial and Corporate Change, 11(3), 529–555.

- Coes, B. (2014). Critically assessing the strengths and limitations of the business model canvas. Master thesis business administration at the University of Twente. Retrieved from http://essay.utwente.nl/64749/1/ Coes_MA_MB.pdf, (Accessed on 18th of June, 2015)

- Damm, A. P. (2009). Ethnic enclaves and immigrant labor market outcomes: Quasi-experimental evidence. Journal of Labor Economics, 27(2), 281-314.

- Denzin, N. (1970). The Research Act in Sociology. Chicago: Aldine.

- Drori, I., Honig, B., & Wright, M. (2009). Transnational entrepreneurship. An emergent field of study. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(5), 1001–1022.

- Dutia, S. G. (2011). Diaspora networks. A new impetus to drive entrepreneurship. Innovations, 7, Winter 2012, 65–72.

- Frignal, E. (2007). Outsourced call centers and English in the Philippines. Word Englishes, 26(3), 331–345.

- Geddes, A. (2001). Immigration and European integration: towards fortress Europe? Refugee Survey Quarterly, 20(1), 229-229

- Ghaziani, A. & Ventresca, M. J. (2005). Keywords and cultural change: Frame analysis of business model public talk 1975 – 2000. Sociological Forum, 20(4), 523–559.

- Gillespie, K., Riddle L., Sayre, E. & Sturges, D. (1999). Diaspora interest in homeland investment. Journal of International Business Studies, 30(3), 623–634.

- Harima, A. (2014). Network dynamics of descending diaspora entrepreneurship: Multiple case studies with Japanese entrepreneurs in emerging economies. Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Innovation, 10(4), 65-92.

- Hoang, H., & Antocic, B. (2003). Network-based research in entrepreneurship: A critical review. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(2), 165-187.

- Hornung, E. (2014). Immigration and the diffusion of technology: The Huguenot diaspora in Prussia. The American Economic Review, 104(1), 84-122.

- International Organization for Migration (2014). Health in the Post-2015 Development Agenda. The Importance of Migrants' Health for Sustainable and Equitable Development. Retrieved from https://www.iom.int/files/live/sites/iom/files/What-We-Do/docs/Health-in-the-Post-2015-Development-Agenda.pdf(Accessed on 30th of March, 2015)

- Kapur, D. (2001). Diasporas and technology transfer. Journal of Human Development, 2(2), 265–286.

- Kloosterman, R., van der Leun, J., & Rath, J. (1999). Mixed embeddedness: (In) formal economic activities and immigrant business in the Netherlands. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 23(2), 253–267.

- Kuznetsov, Y. (2006). Diaspora networks and the international migration of skills: How countries can draw on their talent abroad. Washington DC: World Bank Publications (WBI Development Studies).

- Levitt, P. (2001). Transnational migration: Taking stock and future directions. Global Networks, 1(3), 195–216.

- Lindgardt, Z., Reeves, M., Stalk, G., & Deimler, M. S. (2009). Business model Innovation. When the Game Gets Through, Change the Game. The Boston Consulting Group. Retrieved from http://www.bcg.com.br/documents/ file36456.pdf(Accessed on 11th of March, 2015).

- Lodigiani, E. (2009). Diaspora externalities and technology diffusion. Economie internationale, 115(3), 43-64.

- Magretta, J. (2002). Why business models matter. Harvard Business Review, 80(5), 86-92.

- Meyer, J.-B., & Wattiaux, J.-P. (2006). Diaspora knowledge networks: Vanishing doubts and increasing evidence. International Journal on Multicultural Societies, 8(1), 4–24.

- Morris, M., Schindehutte, M., & Allen, J. (2005). The entrepreneur's business model: Toward a unified perspective. Journal of Business Research, 58(6), 726–735.

- Nielsen, T. M. & Riddle, L. (2009). Investing in peace: The motivational dynamics of Diaspora investment in post-conflict economies. The Journal of Business Ethics, 89(4), 435–448.

- OECD (2013). International Migration Outlook 2013. OECD Publishing. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/migr_outlook-2013-en (Accessed on 31st of October, 2014)

- Osterwalder, A., & Pigneur, Y. (2010). Business model generation: John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken NJ.

- Pavie, X., Hsu, E., Rödle, H. J. T., & Tapia, R. O. (2013). How to define and analyze business model innovation in Service. Research Center, ESSEC Working Paper 1323. Retrieved from https://hal.inria.fr/file/index/ docid/921420/filename/WP1323.pdf(Accessed on 1st of June, 2015).

- Rauch, J. E., & Trindade, V. (2002). Ethnic Chinese networks in international trade. Review of Economics and Statistics, 84(1), 116-130.

- Ray, S., & Cardozo, R. (1996). Sensitivity and creativity in entrepreneurial opportunity recognition: A framework for empirical investigation. The Sixth Global Entrepreneurship Research Conferenceat Imperial College London.

- Riddle, L. (2008). Diaspora: Exploring their development potential. ESR Review, 10(2), 28–36.

- Safran, W. (1991). Diasporas in modern societies: Myths of homeland and return. A Journal of Transnational Studies, 1(1), 83–99.

- Saxenian, A. (2005). From brain drain to brain circulation: Transnational communities and regional upgrading in India and China. Studies in Comparative International Development, 40(2), 33–61.

- Shane, S. (2000). Prior knowledge and the discovery of entrepreneurial opportunities. Organization Science, 11(4), 448-469.

- Tedlock, B. (1991). From participant observation to the observation of participation: The emergence of narrative ethnography. Journal of Anthropological Research, 47(1), 69-94.

- The Department of Tourism in Philippines (2003). Visitor arrivals to the Philippines by country of residence January-December 2003, Retrieved from http://www.wowphilippines.com.ph/(Accessed on 10th of March, 2015)

- The Department of Tourism in Philippines (2013). Visitor arrivals to the Philippines by country of residence January-December 2013, Retrieved from http://www.wowphilippines.com.ph/, (Accessed on 10th of March, 2015)

- Tölölyan, K. (1996). Rethinking diaspora(s): Stateless power in the transnational moment. A Journal of Transnational Studies, 5(1), 36-36.

- Tung, R. L. (2008). Brain circulation, diaspora, and international competitiveness. European Management Journal, 26(5), 298–304.

- Vemuri, S. (2014). Formation of Diaspora Entrepreneurs. ZenTra Working Papers in Transnational Studies 41/2014 (November 2014). Retrieved from http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2519432 (Accessed on 10th of March, 2015)

- Vemuri, S. (2015). Tracing the history of Diaspora business. Paper presented at the 1st Global meeting of The Diaspora & Business Project, Mansfield College, Oxford, July 15-16, 2015

- Wahlbeck, Ö. (2004). Turkish immigrant entrepreneurs in Finland: Local embeddedness and transnational ties. Transnational Spaces: Disciplinary Perspectives. Willy Brandt Conference Proceeding. Edited by Maja Povrzanovic Frykman´. Retrieved from http://ir.nmu.org.ua/bitstream/ handle/123456789/123290/cf519b6ed5914d52a1b3ec489ed283c2. pdf?sequence=1#page=102. (Accessed on 18th of June, 2015)

- Worldbank. (2014). Migration and Remittances: Recent Developments and Out-look. Special Topic: Forced Migration. Migration and Development Brief, 23: 1-2. Retrieved from http://siteresources. worldbank.org/INTPROSPECTS/Resources/3349341288990760745/ MigrationandDevelopmentBrief23.pdf (Accessed on 19th of February, 2015)

- Zabin, C., & Hughes, S. (1995). Economic integration and labor flows: stage migration in farm labor markets in Mexico and the United States. International Migration Review, 29(2), 398-422.

- Zott, C., Amit, R., & Massa, L. (2011). The Business Model: Recent Developments and Future Research. Journal of Management, 37(4), 1019–1042.

Biographical note

Aki Harima is a research assistant and a PhD candidate at the Chair of Small Businesses & Entrepreneurship (LEMEX) at the University of Bremen, Germany. She acquired her MSc in Management at the University of Mannheim (Germany) and BSc in Business Administration at the University of Kobe (Japan). She investigates entrepreneurial activities of diasporans from developed countries in developing and emerging countries from various perspectives such as individual intercultural competencies, networks, strategic management and innovation.

Sivaram Vemuri is currently an Associate Professor of Economics, Waterfront Darwin Business School, Faculty of Law, Education, Business and Arts, Charles Darwin University, Darwin, NT 0909, Australia, and the Director of Administration, Finance and Personnel, Inter-disciplinary.net, Oxford.