Received 1 November 2021; Revised 9 January 2022, 29 January 2022; Accepted 7 February 2022.

This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode).

Ronny Tan, S.Si., Student at Graduate School of Management, Universitas Pelita Harapan, The Plaza Semanggi, Jl. Jend. Sudirman No.50, RT.1/RW.4, Karet Semanggi, Kecamatan Setiabudi, Kota Jakarta Selatan, DKI Jakarta 12930, Indonesia, e-mail: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Ferdi Antonio, Ph.D., M.M., M.A.R.S., Assistant Professor at Graduate School of Management, Universitas Pelita Harapan, The Plaza Semanggi, Jl. Jend. Sudirman No.50, RT.1/RW.4, Karet Semanggi, Kecamatan Setiabudi, Kota Jakarta Selatan, DKI Jakarta 12930, Indonesia, e-mail: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Abstract

PURPOSE: This study investigates how perceived e-leadership and the teleworking output are linked to employee adaptive performance. Further, it seeks to comprehend whether a sense of purpose and organizational commitment have a mediating role. This study proposes a new research model that is empirically tested to predict employee adaptive performance, especially during remote working due to the COVID-19 pandemic. METHODOLOGY: A quantitative survey was conducted in August 2021. Respondents were obtained from 271 teleworkers employed in a reputable private company operating in the financial industry in Indonesia. The data was collected by a questionnaire using a Likert-type scale and then analyzed using PLS-SEM. FINDINGS: Three antecedents are proven to affect employee adaptive performance directly: organizational commitment, followed by teleworking output, and a sense of purpose. Perceived e-leadership affects employee adaptive performance indirectly, and it is mediated through teleworking output, organizational commitment, and sense of purpose. IMPLICATIONS: This insight suggests that management must take care of intrinsic motivation to get the employees performing in the organization. These constructs will play significant roles and, therefore, should be well-planned, well-executed, and seriously measured to strengthen employee adaptive performance in an organization. The research model result shows moderate predictive accuracy strength with medium predictive relevance on employee adaptive performance, giving opportunities to re-use and extend the research model and explore other constructs. Based on the findings, management needs to focus on trust in employees, team motivation, and employee-experience management activities to keep the employees engaged. ORIGINALITY AND VALUE: This is one of the first studies to deploy intrinsic motivation as an antecedent of employee adaptive performance, together with the perceived e-leadership and teleworking output. Corporations will be able to focus on some key areas that are proven to impact employee adaptive performance positively.

Keywords: e-leadership, teleworking, sense of purpose, organizational commitment, employee adaptive performance, COVID-19, intrinsic motivation

INTRODUCTION

“Pervasive technology and data, and talent in the digital age

are already the two key underlying trends shaping the workforce of the future.

The additional remote working trend will complicate the shaping

of the future workplace even further.” (BCG and Verizon, 2020)

Teleworking, particularly working from home, has been around for a long time. It denotes a more adaptable working style not constrained by time, venue, or interaction method. Teleworking requires technological, social, and organizational support, as well as e-leadership practices. Following the pandemic of COVID-19, social distancing, defined as a purposeful physical distance between people (Prin & Bartels, 2020), was adopted as an effective preventative method, mandating remote working. Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) enable people to operate from any location and at any time. In addition, teleworking is also a subject of continual controversy due to the unclear non-work and work boundaries, the individual and social implications of not being physically present in the office, and the risks and advantages of flexible working (Contreras et al., 2020). Socially isolated staff also get disengaged from their regular work environment, resulting in lessened performance and continuous disheartening (Wojcak et al., 2016).

As the business and working environment becomes more dynamic to predict, employees’ capacity and agility to manage the changes and the work dynamics become required abilities. Because of this, adaptive performance, described as employees’ ability to adapt to agile work environments, has gained attention to understand the vibrant nature of employee performance. Adaptive performance can drive encouraging outcomes, for instance, improved performance capability and a successful career (Shoss et al., 2012). It also leads to organizational benefits, such as better change management, organizational learning ability, and conformity to evolving customer expectations (Dorsey et al., 2010). Various research was done in the past to study further the antecedents of adaptive performance, namely, the impact of servant leadership on adaptive performance (Kaya & Karatepe, 2020), extraversion and adaptive performance (Wihler et al., 2017), work ethic, work behavior, and adaptive performance (Javed et al., 2017). The following antecedents of adaptive performance were also studied: learning agility and adaptive performance (Lim et al., 2017), personality and work engagement fit and adaptive performance (Shahidan, 2019), inclusive leadership and adaptive performance (Yu, 2020), empowerment practices and adaptive performance (Huntsman et al., 2021). However, study on intrinsic motivation, especially on the sense of purpose and organizational commitment, and their significance to adaptive performance is challenging to find; this leads to the research gap that the author is keen to explore.

Individual purpose can act as guidance during times of crisis, supporting individuals in confronting and navigating uncertainty more effectively. Additionally, it mitigates the detrimental consequences of chronic stress. People with a firmer sense of purpose are more resilient and recover from unfavorable circumstances quickly (Schaefer et al., 2013). Purpose can significantly impact the work experience, associated with greater employee engagement, dedication to the organization, and human emotions. Individuals, who align their purpose with their work, experience more meaning in their roles, increasing their productivity and likelihood to exceed their colleagues. According to a McKinsey & Company study, employees’ purposefulness correlates positively with their company’s EBITDA margin (Dhingra et al., 2020). Employee adaptability has become increasingly vital for many organizations as the nature of work has changed, necessitating the ability to deal with uncertain competitive conditions and constant technological advancement (Charbonnier-Voirin & Roussel, 2012). Individually, adaptive performance can result in beneficial results, such as increased performance capability and job success (Shoss et al., 2012). Organizational commitment is correlated with several positive outcomes, including the advancement of job performance, motivation, participation, and organizational behaviors (Jacobs, 2008; Jønsson & Jeppe Jeppesen, 2013; Meyer et al., 2002; Meyer & Allen, 1991; Nazir et al., 2016).

The purpose of this research is to investigate the relationship between e-leadership, teleworking output, sense of purpose, organizational commitment, and employee adaptive performance. Studies that linked those variables to predict employee adaptive performance are limited, especially in remote working during the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, a new conceptual framework is proposed. The dependent variable is employee adaptive performance; Perceived e-leadership, teleworking output, sense of purpose, and organizational commitment are independent variables. This study is also keen to determine whether a sense of purpose or organizational commitment can effectively mediate perceived e-leadership and teleworking output into employee adaptive performance. This conceptual framework will be empirically tested on employees in a medium-to-large organization doing teleworking during the COVID-19 pandemic.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Adaptive performance refers to the ability of an individual to adapt to changing working conditions. Employees exhibit adaptive behavior when they modify their behaviors to the needs of working conditions and new occurrences (Pulakos et al., 2000). A study by Pulakos et al. (2000) proposed the first globally recognized concept of adaptive performance, which included the following eight dimensions of adaptive performance: dealing with uncertain or unpredictable work situations; responding creatively to problems; managing work stress; learning new tasks, technologies, and procedures; demonstrating interpersonal adaptability; demonstrating cultural adaptability; and demonstrating physically oriented adaptability. Another research from Charbonnier-Vsoirin and Roussel (2012) tested the eight dimensions of adaptive performance by Pulakos et al. (2000), and constructed another tool to assess individual adaptability across five dimensions: creativity, responsiveness to crises or unexpected events, interpersonal adaptation, training, and managing stress. Creativity refers to a worker’s ability to find solutions for, or new approaches to, complex or previously unknown problems. Responsiveness to crises or unexpected events refers to the ability to manage priorities and to adapt to new situations at work. Interpersonal adaptation represents a worker’s ability to adjust their interpersonal style to work effectively, whether within their own organization or in partner firms. Training describes the tendency to initiate action to promote personal development. And the last one, managing stress, refers to an individual’s ability to maintain his or her composure and to channel his or her team’s stress.

E-leadership is defined as virtual communication, knowledge management, and system advancement as a result of ICT, resulting in a “total leadership system” in which leadership and technology are closely tied and affect each other (Liu et al., 2020). New ideas such as “digital leadership” have entered the discussion in recent years and are increasingly associated with e-leadership (Roman et al., 2019). Effective e-leaders are proficient in managing virtual environments, appreciate the current ICT tools, make appropriate selections, and acquire the technical competencies necessary to use the ICT needed (Van Wart et al., 2017). Together with communication, social, team, change management skills, they are required for effective e-leadership. Finally, successful e-leaders integrate important ICT with a physical or face-to-face approach, get the right balance out of them, and understand how to utilize them professionally.

Teleworking, telecommuting, or remote working is a broad term that refers to any paid work performed at a distance from the organization’s physical location. Employees accomplish organizational goals using ICT and occasionally manage their own time (Tietze & Musson, 2005). Teleworking may provide numerous benefits. It has been established in previous studies that teleworking improves job performance, job happiness, work-life balance, stress levels, and desire to remain with the organization (Coenen & Kok, 2014; Fonner & Roloff, 2010; Kossek et al., 2006; Vega et al., 2015). Additionally, telecommuting lowers commute time, traffic congestion, air pollution (Tremblay & Thomsin, 2012), and job possibilities for women with school children and the disabled (Morgan, 2004). A study from Kazekami (2020) indicates that teleworking boosts staff happiness and job satisfaction. Telecommuters can be more productive because they can work when convenient and are less distracted by coworkers (Golden & Veiga, 2008). It also decreases the human and organizational costs of absenteeism by allowing workers to complete their job commitments even when access to the office is not possible (Nakrošienė et al., 2019). However, teleworking does have some drawbacks that must be considered. A study by Cooper and Kurland (2002) explained that teleworking diminishes the learning gains associated with coworkers. Another danger is social isolation from work teams, resulting in disengagement from their jobs and, eventually, worse performance (Wojcak et al., 2016). Long-term isolation degrades employee performance and increases the likelihood of employee turnover and work-family conflict. Therefore, arguably, it only fits self-organized individuals who are good at time management. In addition, Maruyama and Tietze (2012) found that teleworking might increase employee concerns about the prospect of career possibilities being lost due to lower visibility. One of the biggest concerns among supervisors regarding remote working is the risk of depleted employee performance (Contreras et al., 2020). Finally, teleworking poses ethical problems for e-leaders, such as worker exploitation and information overload, which interfere with workers’ personal lives (Cortellazzo et al., 2019; Gálvez et al., 2020).

“Purpose” has become a management focus over the last decade. It has been featured in the titles of hundreds of business and management books and thousands of reports since 2010 (Blount & Leinwand, 2019). The purpose is described as individuals’ identification of highly valued, primary goals whose success is expected to get them closer to attaining their ultimate potential and providing them with profound satisfaction (Kosine et al., 2008). A recent study found that a sense of purpose is significantly related to intrinsic motivation, net the effects of autonomy, self-efficacy, and connection (or the three known antecedents of self-determination theory), and positively associated with working hard and working smart (Good et al., 2021). An earlier study by Ryff and Keyes (1995) explained that there are seven indicators to measure purpose, which are, has goals in life and a sense of directedness; feels there is meaning to present and past life; holds beliefs that give life purpose; has aims and objectives for living; lacks a sense of meaning in life; has few goals or aims; lacks a sense of direction; does not see purpose in past life ; has no outlooks or beliefs that give life meaning. Research from Hill et al. (2016) indicates that individuals with a higher sense of purpose in life tended to have greater engagement in life, higher income, and net worth. In relation to corporate work, companies with a solid sense of purpose are more likely to accept diversity, promote employee innovation, and provide the necessary direction for the staff to achieve their maximum potential (Deloitte, 2014), which strengthen what was suggested earlier by Spence and Rushing (2009) that the secret ingredient of extraordinary companies is the purpose.

In management and organizational behavior literature, commitment to an organization is a well-established notion. While organizational commitment can be defined in various ways, this research adopts Meyer and Allen’s model (Meyer et al., 2002), which comprises three dimensions: affective, normative, and continuation. Affective commitment is characterized as an individual emotional relationship, identification, and engagement with the organization and has been linked to a wish to stay with and bring impact to the greater whole (Jønsson & Jeppe Jeppesen, 2013; Nazir et al., 2016; Ohana & Meyer, 2016; Wang et al., 2010). Normative commitment refers to an employee’s loyalty and perceived obligation to remain with the organization out of a sense of responsibility, shared values, or reciprocity for the organization’s investment in the individual (Jacobs, 2008; Jønsson & Jeppe Jeppesen, 2013; Meyer & Allen, 1991; Nazir et al., 2016). Continuance commitment is motivated by economic transactions and reflects an employee’s desire to stay with the company owing to perceived advantages, a lack of appealing alternatives, or a high switching cost (Meyer & Allen, 1991; Thye et al., 2014). It is worth mentioning that organizational commitment is a Western cultural concept. Hence, the extent to which it can be extended to non-Western cultures has been an interesting subject of discussion. Previous research has indicated that organizational commitment might vary among different cultures (Bachkirov, 2018).

HYPOTHESIS DEVELOPMENT

E-leadership impact on organizational commitment and sense of purpose

A study by Boal and Hooijberg (2000) explained that leadership should be focused on the organization’s development of meaning and purpose. Gerry Anderson, the former CEO of DTE Energy, exemplifies how leadership may be critical to an employee’s sense of purpose. In 2008, he created a film articulating his staff’s larger mission. The film embodied the new mission statement of DTE: “We serve with our energy, which is the lifeblood of communities and the engine of growth.” The outcome was significant: engagement scores increased. Transformation began. For five consecutive years, the company earned the Gallup Great Workplace Award. Furthermore, from the end of 2008 to 2017, DTE’s stock price more than quadrupled (Quinn & Thakor, 2018).

Another study conducted by Iriqat and Khalaf (2017) found that e-leadership is empirically connected to virtual team members’ perceptions of organizational commitment. Therefore, the following hypotheses are proposed:

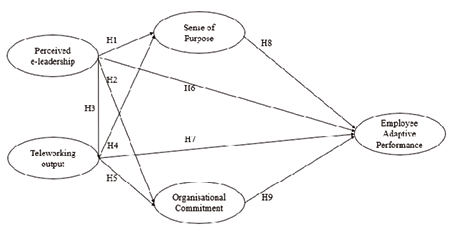

H1: Perceived e-leadership positively affects sense of purpose.

H2: Perceived e-leadership positively affects organizational commitment.

E-leadership and teleworking impact on employee adaptive performance

Social interaction strengthens traditional leadership. Nevertheless, in virtual environments, this impact is facilitated by ICTs, which change workers’ behaviors, feelings, opinions, and performance (Van Wart et al., 2017). E-leaders must be physically and psychologically close to their staff in mitigating the undesirable effects of physical and psychological distance (Stokols et al., 2009). E-leaders must establish trust in their relationships to facilitate the interchange of ideas; they must also facilitate an information stream and produce innovative results (Avolio et al., 2014).

Darics (2017) emphasized that management and leadership functions are integrated with a teleworking situation. Managers are accountable for managing performance, implementing necessary solutions, and maintaining a team identity by developing and sharing the organization’s vision, values, and goals in a trusting work environment. Teleworking creates a considerable increase in the volume and velocity of communication; the expansion of communication channels that e-leaders need to be experts on; and the importance for e-leaders to adopt new technological solutions (Van Wart et al., 2016). Therefore, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H3: Perceived e-leadership positively affects teleworking output.

H6: Perceived e-leadership positively affects employee adaptive performance.

H7: Teleworking output positively affects employee adaptive performance.

Teleworking impact on sense of purpose and organizational commitment

For many individuals, the pandemic has halted their progress toward personal life goals and meaningful and rewarding work, affected their sense of purpose, and compelling them to give their days new structures and meaning (Meyer-Kalos et al., 2020). Likewise, teleworking might positively affect the employees’ purpose as they spend much less time commuting and hence will have more time with their family and improve the work-life balance. Therefore, it is assumed that an effectual teleworking output will positively impact an employee’s sense of purpose.

Researchers and practitioners have taken opposing views on the predicted effects of telework on affective commitment, with some predicting a positive effect and others indicating a detrimental effect. A study by Lim and Teo (2000) suggested that staff with higher organizational commitment will be less favorable to teleworking. In addition, another research from Piper (2004) indicates that teleworking does not increase staff organizational commitment. On the contrary, Golden (2006) found that teleworking is positively related to staff commitment. Wang et al. (2020) also found that continuance commitment is positively associated with psychological and physical isolation.

There is an additional reason to assume that telecommuting could improve employee commitment to the company. These reasons arise mainly from the option to have a work-scheduling arrangement that the employee desires, so this line of thinking would only apply to employees who choose to telecommute voluntarily. Positive job experiences that meet their expectations and basic needs are the primary source of affective commitment. These employees believe that their aims and values align with those of the company. Employees who can work from home are more likely to think that their needs are being met and that the organization’s values are aligned with their own. The literature on perceived organizational support adds to the evidence for a beneficial link between teleworking and affective commitment. Previous research suggested that perceived organizational support predicts organizational commitment (Aubé et al., 2007; Makanjee et al., 2006). As such, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H4: Teleworking output positively affects sense of purpose.

H5: Teleworking output positively affects organizational commitment.

Sense of purpose and organizational commitment impact on employee adaptive performance

Organizational culture demonstrates a distinct sense of purpose and devotion to the organization’s objective, which improves employee effectiveness in achieving goals (Narayana, 2017). The greater the individual’s experience of purpose and meaning, the stronger their intrinsic work satisfaction, work involvement, and organization-based self-esteem (Milliman et al., 2003). Prior research has also discovered a connection between organizational commitment and employee performance (Cesário & Chambel, 2017). Furthermore, according to a study conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic in a hospitality industry located in the U.S., employees’ organizational commitment positively impacted their job performance (Wong et al., 2021). The following hypotheses are proposed based on the objective to find out whether prior research is still relevant for employee adaptive performance in contrast to traditional employee performance:

H8: Sense of purpose positively affects employee adaptive performance.

H9: Organizational commitment positively affects employee adaptive performance.

Figure 1 below explains the conceptual framework of this research.

Figure 1. Conceptual framework

METHODOLOGY

This study discovers the relationship between e-leadership, teleworking output, and employee adaptive performance, with a sense of purpose and organizational commitment as mediating roles. It deploys quantitative research with a survey, in which the data is collected cross-sectionally and analyzed with Structural Equation Modelling (SEM). The approach used is PLS-SEM because it is adequate to analyze the explanatory and prediction of the proposed research model (Hair et al., 2019). Moreover, PLS-SEM is suitable for a complex model with several variables where the influences can be evaluated simultaneously (Hair et al., 2019).

Population and sampling size

Respondents of this study are 271 full-time employees of a privately owned, reputable financial industry company in Indonesia with headquarters in Jakarta, Indonesia. They have been doing work from home (more than 70% of the staff) since April 2020 during the COVID-19 outbreak in Indonesia. It is a census type of data gathering, conducted in August 2021 using a Google form to collect data. As this research uses 271 respondents, the minimum sampling requirement of 160 respondents is therefore met (Kock & Hadaya, 2018).

Questionnaire and measures

An online survey using Google form was deployed to gather the data from the respondents. It has two parts: the first part of the online survey describes the questions about the respondents’ socio-demographic information, and the second part consists of the questions related to the variable used in this study. All variables and indicators used in this study are gathered from previous credible research. The e-leadership variable is taken from Van Wart et al. (2017), where there are four indicators used: e-communication skills (EL1), e-social skills (EL2), e-team building skills (EL3), and e-trustworthiness (EL4). A teleworking output variable is adopted from Nakrošienė et al. (2019), which uses four indicators in the areas of supervisor’s trust (TW1), possibility to save travel expenses (TW2), and the possibility to work during the most productive time (TW4). Research from Steger et al. (2012) is used as a reference for the sense of purpose variable, in which there are three indicators to test from greater good motivation (SP1), positive meaning (SP2), and contribution to meaning-making (SP3). The organizational commitment variable is adopted from Meyer and Allen’s (1991) definition, which uses the three-component framework of affective (OC1, OC2), continuance, and normative (OC3) commitment. Furthermore, employee adaptive performance as a target construct uses previous research from Charbonnier-Voirin and Roussel (2012) with four indicators used: solving problem creatively (EP3), training and learning effort (EP5), interpersonal adaptability (EP6), physical adaptability (EP7), and they are measured with the unidimensional approach.

All indicators are measured using a five-point Likert-type scale (from 1 = strongly disagree until 5 = strongly agree), adopted from the English language, and then translated into Bahasa Indonesia. The questionnaire was content-validated by a small test population before the survey was done to ensure the questionnaire was well understood and had no ambiguity.

This study employs the PLS-SEM data analysis method to answer the research question. PLS-SEM can be used for research with an explanatory and predictive approach, complex, and many constructs (Hair et al., 2019). In addition, PLS-SEM does not require normal data distribution. SmartPLS software version 3.3.3 is used to perform the calculation (Memon et al., 2021; Ringle et al., 2015) and is done in two stages. The first stage is the outer model assessment to measure the validity and reliability of the used indicators. The second stage is the structural model assessment to estimate the predictor strength of the proposed research model through R2, Q2, and RMSE values. Post measuring the research model quality, a hypothesis validity check is done by measuring the significance and coefficient, followed by the mediation analysis.

RESULTS

Table 1 provides a socio-demographic profile of the 271 respondents who participated in this survey. Most of them are aged 28-37 (44%), married with children (61%), living with family and children (51%), have a bachelor’s degree (78%), with a length of service above five years (46%), working from home (WFH) (88%), and a salary range of USD 701–1400 (38%).

Measurement model (outer model) assessment

After collecting the respondents’ profiles, data processing was done to determine the relationship among constructs. Before deciding the relationship between the constructs, all data had to fulfill the validity and reliability criteria in the measurement model analysis.

Table 1. Socio-demographic profile of respondents

|

Description |

Number of respondents |

Percentage (%) |

|

|

Gender |

Male |

146 |

54 |

|

Female |

125 |

46 |

|

|

Age |

18-27 |

32 |

12 |

|

28-37 |

119 |

44 |

|

|

38-47 |

100 |

37 |

|

|

48-57 |

20 |

7 |

|

|

Marital Status |

Single |

71 |

26 |

|

Married without children |

35 |

13 |

|

|

Married with children |

165 |

61 |

|

|

Current Living Condition |

Living alone |

51 |

19 |

|

Living with friend |

3 |

1 |

|

|

Living with family |

80 |

29 |

|

|

Living with family and children |

137 |

51 |

|

|

Highest Education |

High School |

3 |

1 |

|

Diploma |

24 |

9 |

|

|

Bachelor’s degree |

212 |

78 |

|

|

Master’s degree |

32 |

12 |

|

|

Length of Employment |

0-1 year |

20 |

7 |

|

1-3 year |

74 |

27 |

|

|

3-5 year |

52 |

19 |

|

|

> 5 years |

125 |

46 |

|

|

Working Arrangement |

1 Day WFH per week |

4 |

1 |

|

2 Day WFH per week |

7 |

3 |

|

|

3 Day WFH per week |

9 |

3 |

|

|

4 Day WFH per week |

13 |

5 |

|

|

Full WFH |

238 |

88 |

|

|

Monthly Salary Range |

< USD 700 |

62 |

23 |

|

USD 701 - 1400 |

103 |

38 |

|

|

USD 1401 - 2100 |

43 |

16 |

|

|

USD 2101 - 3500 |

32 |

12 |

|

|

> USD 3501 |

25 |

9 |

|

|

Prefer not to answer |

6 |

2 |

|

Table 2. Construct reliability and validity

|

Variable |

Indicators |

Outer loading |

Cronbach’s Alpha |

Composite reliability |

AVE |

|

Perceived E-Leadership |

EL1: “My leader communicates very clearly through electronic media.” |

0.837 |

0.818 |

0.880 |

0.649 |

|

EL2: “My leader uses richer media (such as face-to-face meetings, telephone, and virtual conferencing) when appropriate.” |

0.854 |

||||

|

EL3: “I participate during the virtual team building conducted by my leader.” |

0.712 |

||||

|

EL4: “In leading virtually, my leader has trustworthy integrity.” |

0.811 |

||||

|

Teleworking Output |

TW1: “I think my employer trusts me a lot when providing the opportunity to work from home.” |

0.854 |

0.704 |

0.833 |

0.625 |

|

TW2: “I work from home to save travel expenses.” |

0.776 |

||||

|

TW4: “When working from home, I can work during the most productive time.” |

0.738 |

||||

|

Sense of Purpose |

SP1: “My work gives me the feeling that this is what I was meant to do.” |

0.826 |

0.842 |

0.905 |

0.761 |

|

SP2: “I know my work makes a positive difference in the world.” |

0.905 |

||||

|

SP3: “The work I do serves a greater purpose.” |

0.884 |

||||

|

Organizational Commitment |

OC1: “I am willing to put in a great deal of effort beyond that normally expected in order to help this organization to be successful.” |

0.876 |

0.853 |

0.900 |

0.694 |

|

OC2: “I really care about the fate of this organization.” |

0.871 |

||||

|

OC3: “This organization really inspires the very best in me in the way of job performance.” |

0.802 |

||||

|

OC4: “I would accept almost any type of job assignment in order to keep working for this organization.” |

0.778 |

||||

|

Employee Adaptive Performance |

EP3: “When new or ill-defined work situations arise in your job, I use a variety of sources/types of information to come up with an innovative solution.” |

0.774 |

0.796 |

0.868 |

0.623 |

|

EP5: “I look for every opportunity that enables me to improve my performance.” |

0.862 |

||||

|

EP6: “Developing good relationships with all my counterparts is an important factor of my effectiveness.” |

0.792 |

||||

|

EP7: “I strive to adapt, however difficult, to the working conditions I am in during working from home.” |

0.724 |

Table 2 shows that all indicators have outer loadings > 0.708 as required. Construct reliability can be seen on values in the range of 0.70 and 0.95, and thus it can be concluded that the construct reliability test is accepted. AVE measures a convergent validity check, where all values have AVE > 0.50, indicating all constructs explain at least 50 percent of the variance of its items (Hair et al., 2019).

The Heterotrait-Monotrait (HT/MT) Ratio of the correlations is used for the discriminant validity test. Research from Henseler et al. (2015) recommends using a lower and more conservative threshold value of 0.85 when constructs are conceptually more distinct. Table 3 (HT/MT Ratio) shows that all HT/MT values are well under the 0.85 thresholds for all variables. It concludes that all indicators used in this research model are well discriminated against to measure their respective construct. As a conclusion of the outer model assessment, all indicators in this model are reliable (by CA, CR), and valid to measure construct (by AVE), and specific (by HT/MT).

Table 3. Discriminant validity

|

|

Employee Adaptive Performance |

Organizational Commitment |

Perceived E-Leadership |

Sense of Purpose |

|

Employee Adaptive Performance |

||||

|

Organizational Commitment |

0.750 |

|||

|

Perceived E-Leadership |

0.552 |

0.546 |

||

|

Sense of Purpose |

0.605 |

0.715 |

0.541 |

|

|

Teleworking Output |

0.690 |

0.493 |

0.585 |

0.371 |

Structural model (inner model) assessment

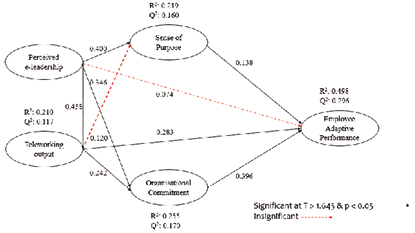

Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) is utilized to validate collinearity. The result of the VIF test in this model has shown that all values are below 3, indicating there is no collinearity issue in the data. Goodness-of-fit is not compatible with PLS-SEM as suggested by (Hair et al., 2019). This research uses R2 as a coefficient of determination to measure predictive accuracy and Q2 as cross-validated redundancy to measure predictive relevance to test the structural model. Employee adaptive performance has R2 = 0.498 and Q2 = 0.296, indicating that this variable is meaningful and has moderate predictive accuracy with medium predictive relevance. PLSpredict is also applied, and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) values are tested between the Linear Model (LM) value of each indicator compared to the PLS value of each indicator. 3 out of 4 employee adaptive performance indicators have lower RMSE values in PLS. Therefore it concludes that this research model has medium predictive power (Shmueli et al., 2019).

Hypothesis testing and mediation analysis

Hypothesis testing was performed to determine the impact of the independent variables on the dependent variables and determine whether the hypotheses proposed by this research were supported. A bootstrapping approach is used to assess the significance of the data. A cut-off value of 1.645 (T-statistic ≥ 1.645, one-tail, 95% significance level) is used as the criteria to understand if the hypotheses are supported or not.

The outcome of the hypothesis testing is shown in Table 4. In addition, mediation analysis is also conducted to determine if the teleworking output, a sense of purpose, and organizational commitment could mediate the impact of perceived e-leadership on employee adaptive performance. In conducting the mediation assessment in this model, the direct and indirect effects are also assessed.

Table 4. Coefficient and significance

|

Hypothesis |

Standard Coefficient |

T-statistic |

p-value |

Results |

|

e-leadership → sense of purpose |

0.400 |

4.980 |

0.000 |

H1 Supported |

|

e-leadership → organizational commitment |

0.346 |

4.558 |

0.000 |

H2 Supported |

|

e-leadership → teleworking output |

0.458 |

6.115 |

0.000 |

H3 Supported |

|

Teleworking output → sense of purpose |

0.120 |

1.479 |

0.070 |

H4 Not Supported |

|

Teleworking output → organizational commitment |

0.242 |

2.864 |

0.002 |

H5 Supported |

|

Perceived e-leadership → employee adaptive performance |

0.074 |

1.024 |

0.153 |

H6 Not Supported |

|

Teleworking output → employee adaptive performance |

0.283 |

4.901 |

0.000 |

H7 Supported |

|

Sense of purpose → employee adaptive performance |

0.138 |

1.959 |

0.025 |

H8 Supported |

|

Organizational commitment → employee adaptive performance |

0.396 |

6.715 |

0.000 |

H9 Supported |

|

Employee Adaptive Performance |

R2 |

Q2 |

||

|

0.498 |

0.296 |

It is explained in Table 4 and Figure 2 that there are seven hypotheses that are supported with t-statistic >= 1.645, p-value < 0.05, and positive standard coefficients. Teleworking output, organizational commitment, and sense of purpose positively affect employee adaptive performance. Similarly, perceived e-leadership and teleworking output positively affect organizational commitment. Perceived e-leadership also positively affects teleworking output and sense of purpose.

Figure 2. Research model result

The other two hypotheses (H4 and H6) are not supported as they have t-statistic < 1.645 and p-value >= 0.05). The relationship between teleworking output and sense of purpose is insignificant. Similarly, the perceived e-leadership relationship to employee adaptive performance is also insignificant.

According to the mediation analysis (see Table 5), all three mediator constructs tested in this study (teleworking output, sense of purpose, and organizational commitment) have a p-value under the threshold of 0.05, indicating that they are all effective mediators of perceived e-leadership towards employee adaptive performance.

Table 5. Specific indirect effect/mediation analysis

|

Path |

Standard Coefficient |

T-statistic |

p-value |

|

Perceived E-Leadership → Teleworking Output → Employee Adaptive Performance |

0.130 |

3.577 |

0.000 |

|

Perceived E-Leadership → Teleworking Output → Organizational Commitment |

0.111 |

2.227 |

0.013 |

|

Perceived E-Leadership → Sense of Purpose → Employee Adaptive Performance |

0.055 |

1.779 |

0.038 |

|

Perceived E-Leadership → Organizational Commitment → Employee Adaptive Performance |

0.137 |

3.538 |

0.000 |

|

Teleworking Output → Organizational Commitment → Employee Adaptive Performance |

0.096 |

2.662 |

0.004 |

The research also demonstrates that teleworking output is an effective mediator (t-statistic: 2.227) between perceived e-leadership and organizational commitment. Organizational commitment (t-statistic: 2.662) also effectively mediates teleworking output towards employee adaptive performance.

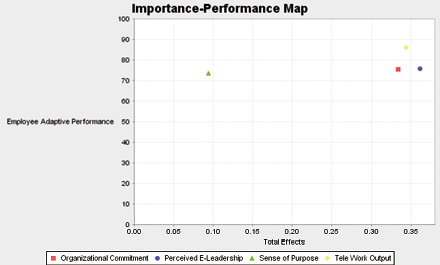

Importance and performance matrix analysis

The Importance-Performance Map Analysis (IPMA) gives management insights into which areas are more important to a target construct, even when the construct or indicator is underperformed (Ringle & Sarstedt, 2016).

Figure 3. Importance-performance map on employee adaptive performance (constructs, unstandardized effect)

The target chosen for the IPMA is the employee adaptive performance variable. Figure 3 explains that perceived e-leadership is the essential construct (with total effect of 0.362) to employee adaptive performance (although it is not the most performing among four constructs) while teleworking output and organizational commitment share similar importance with total effects of 0.344, and 0.334 respectively. It is also understood that sense of purpose is indicated as the least essential construct to employee adaptive performance, with total effect of 0.095. Figure 3 also shows that teleworking output is the highest performance construct, signifying the positive impact on employee adaptive performance.

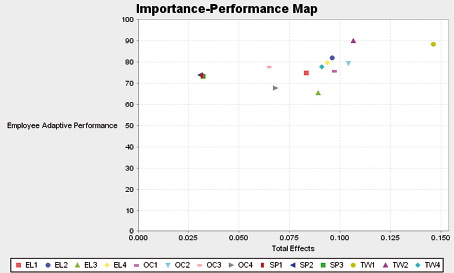

Figure 4. Importance-performance map on employee adaptive performance (indicators, unstandardized effect)

This finding aligns with previous research by Lim & Teo (2000), indicating that teleworking gives married individuals more flexibility in balancing work and family matters. It is also known that 61% of the respondents are married with children.

The IPMA is also used to assess the indicators. Figure 4 shows that the TW1 indicator (“I think my employer trusts me a lot when providing the opportunity to work from home.”) has the highest importance (total effect: 0.146) and the second highest performance (MV performance: 88.284) among all indicators being tested in this study. This result shows that trust from employer to employee is crucial during remote working time and shall be maintained to keep the employee adaptive performance high. EL3 (“I participate during the virtual team building conducted by my leader.”) and OC4 indicators (“I would accept almost any type of job assignment in order to keep working for this organization.”) are the two lowest performance indicators (MV performance: 65.560 and 67.651 respectively). EL3 is associated with team motivation, while OC4 is linked to a strong desire to keep membership (level of staff engagement).

DISCUSSION

This study aims to understand how perceived e-leadership and teleworking output influence employee adaptive performance with a sense of purpose and organizational commitment as mediating roles.

The research outcome suggests that perceived e-leadership positively impacts sense of purpose, organizational commitment, and teleworking output. However, the study also found that perceived e-leadership itself does not directly affect employee adaptive performance. This non-supported hypothesis is different from previous research findings. One way to explain this is to know that the last literature on e-leadership was based on voluntary remote working conditions and not during the “crisis mode” of significant uncertainties triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic, impacting management and staff well-being, habits, and expectations. This finding also suggests that e-leadership is not merely about the effectiveness of ICT adoption by senior leadership. Leadership during the non-voluntary remote working condition also requires two-way trust: the employer’s trust to employees and employees to the employer. Management that has trust issues in their employees will continue to be concerned about productivity losses caused by teleworking. Research conducted by Parker et al. (2020) indicates that a lack of trust in employees results in micro-management and excessive control, both of which jeopardize employee performance. The IPMA diagram (Figure 4) signifies that the TW1 indicator (employer’s trust during remote working) has the highest importance among all indicators used in this study to influence employee adaptive performance.

Perceived e-leadership as a total effect, eventually positively affects employee adaptive performance due to the mediating power of teleworking output, organizational commitment, and a sense of purpose. In other words, e-leadership capability alone is insufficient to maintain high employee adaptive performance. It shall be supplemented with either: an excellent teleworking policy, a solid organizational commitment, or a strong sense of purpose.

This study demonstrates the crucial role of teleworking output as both a mediator and independent variable that positively impacts employee adaptive performance. Teleworking output also has a positive influence on organizational commitment. The fact that the TW1 indicator (employer’s trust during remote working) has the highest importance among all indicators gives essential insight to senior management that during the COVID-19 pandemic, most employees prefer a more flexible working model post-pandemic. Research conducted by Alexander et al. (2021) on employees expectations on working flexibility shows that entirely on-site is down from 62 to 37%, hybrid work is up from 30 to 52%, and fully remote is up from 8 to 11% during the pre-pandemic and post-pandemic time, respectively. This disconnect is more profound than most employers realize, and an increased risk in disengagement and employee attrition rate is climbing. 91% of employees prefer to work from home more often, at least once a week (Robert Walter Groups, 2020), while another research found that most employees around the globe are keen to work no less than three days per week going forward (Alexander et al., 2021). Even more, 83% of Indonesian employees prefer to have more flexible teleworking, which is higher than the global average of 73% (Microsoft, 2021). This aspiration shall be seriously addressed by corporations, particularly the human capital leaders.

This study indicates that teleworking output is not proven to impact a sense of purpose. A logical explanation for this finding is that the workload or work pressure is even higher during working from home. The increased workload occurs due to teleworking during the COVID-19 pandemic, which has negatively impacted many businesses, putting additional pressure on them to deliver more (by doing more work from home). Fauville et al. (2021) discovered that “Zoom Fatigue,” which refers to the fatigue experienced during or after video conferencing with any platform, exists. Those employees who attend more frequent and prolonged meetings, report feeling more tired than those who attend fewer and shorter meetings. Furthermore, employees who are fatigued after a virtual meeting are more likely to have a negative attitude toward it. This finding is consistent with previous research by Wrzesniewski (2020), mentioning that people who work alone (or only connect digitally) and away from their usual surroundings may encounter a sense of meaning and purpose degradation. This research also shows that teleworking output has a positive influence on organizational commitment. This insight confirms the hypothesis based on the indirect linkage that perceived organizational support has a beneficial link between telework and affective commitment. Perceived organizational support is a predictor of affective organizational commitment. Likewise, both sense of purpose and organizational commitment positively impact employee adaptive performance, as previously hypothesized. This insight suggests that management must take care of intrinsic motivation to get employees performing in the organization. These constructs will play significant roles and, therefore, should be well-planned, well-executed, and seriously measured to strengthen the employee adaptive performance in an organization.

The IPMA diagram also gives critical insights into the two lowest performance indicators (team motivation and level of staff engagement in the organization). During remote working conditions, management must put extra effort into these areas. By being available, listening to employees, demonstrating compassionate leadership, showing calmness and optimism, and supporting employees to find meaning or purpose during a crisis, leaders can build employee resilience to boost the staff’s motivation. This insight is also consistent with the research from Emmett et al. (2020), suggesting that by aligning the individual purpose and organizational purpose and values, work effectiveness, engagement, and well-being improved by 20.3%, 49%, and 49.3%, respectively. Employees with a high sense of purpose will navigate the high level of uncertainties better, have four times higher engagement and five times higher well-being.

Companies may also need to organize employee engagement or employee-experience management activities, including virtual weekly activities, happy hours, instant appreciation, virtual games, fun challenges, and e-learning. Companies can also consider arranging family engagement training to keep the employees’ children well-managed at home while their parents are working from home (Sarkar, 2020). It is also essential for senior leadership to proactively protect employees’ health and safety, build employees’ social capital, maintain employees’ psychological safety at a healthy level, and be transparent during the remote working period of COVID-19. These “employee experience” practices boost employee morale, reinforce team connections, and make employees feel motivated and committed during the pandemic (Chanana & Sangeeta, 2020; Emmett et al., 2020).

CONCLUSION

This new norm of work may persist globally even after the pandemic has ended. This shift has disrupted the business model, improved how companies operate and function, and changed how employers and employees interact. Thus, for effective e-leadership, employee performance, and long-term company performance, corporations must adopt and deploy a certain degree of work flexibility. Many employers are keen to resume face-to-face or traditional types of work, while employees, on the other hand, are not. Leaders that refuse to adapt will face the risk of losing talent.

Furthermore, in the future of the workforce, flexible working arrangements will be increasingly tailored considering the company’s direction. Staff individual conditions and next-generation enabling technology will help make this process more efficient and effective. Additionally, teleworking will give more options to access remote or foreign talents, which is getting important too, especially during continuous digital transformation and digital talent scarcity in the market.

The impact of technology advancement and the new working model will not change the fact that companies deal with complex human emotions with self-perceptions and blind spots. Consequently, the future of the companies’ success also needs to build intrinsic motivation, such as organizational commitment and purpose. With a solid purpose and commitment to the organization, employees are on the right track to develop unique human competencies that are challenging to automate, such as creativity, partnership, communication, and emotional/spiritual intelligence, which are crucial human capabilities to the business success.

Limitations and future directions

This empirical study has met the research objective and answered the hypotheses. Nevertheless, some research limitations may be relevant for future research. The first limitation is perceived e-leadership as one of the independent variables, in which the detail is collected from the employees’ perception. This personal perception might have information bias impacting the accuracy of the data analyzed. Secondly, data collected in this study is taken from a company, of which the results could vary depending on the rate of technology adoption. Therefore, it is suggested to enlarge the research to companies with different technology adoption levels. Thirdly, the current research model has also not included any moderating variables towards employee adaptive performance. Further studies could test the moderating effect of some constructs, such as job stress, work demand, or the employees’ psychological capital.

This study has also opened some ideas for future research. The research model result indicates moderate predictive accuracy strength with medium predictive relevance; therefore, the model could be improved by exploring other constructs. 88% of the respondent in this study fully work from home. Further research can be done to analyze deeper if there is any different outcome on hypotheses when the company is doing a specific ratio of hybrid working, e.g., in the proportion of 50:50 of working from home and working from the office. It is worth exploring which virtual team building has the most significant impact on employee adaptive performance. In addition, future research could also observe further how employee adaptive performance influences collective performance.

Acknowledgment

We thank the extremely helpful comments of two anonymous reviewers.

References

Alexander, A., De Smet, A., Langstaff, M., & Ravid, D. (2021). What employees are saying about the future of remote work. McKinsey & Company. Retrieved from https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/organization/our-insights/what-employees-are-saying-about-the-future-of-remote-work

Aubé, C., Rousseau, V., & Morin, E. M. (2007). Perceived organizational support and organizational commitment. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22(5), 479–495. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940710757209

Avolio, B. J., Sosik, J. J., Kahai, S. S., & Baker, B. (2014). E-leadership: Re-examining transformations in leadership source and transmission. The Leadership Quarterly, 25(1), 105–131. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2013.11.003

Bachkirov, A. A. (2018). “They made me an offer I couldn’t refuse!” Organizational commitment in a non-Western context. Evidence-Based HRM: A Global Forum for Empirical Scholarship, 6(1), 77–93. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBHRM-09-2016-0022

BCG and Verizon. (2020). How to lead differently in the workplace of the future. Retrived from https://enterprise.verizon.com/resources/whitepapers/leading-in-the-future-workplace/trends-of-the-future/

Blount, S., & Leinwand, P. (2019). Why are we here?: If you want employees who are more engaged and productive, give them a purpose—one concretely tied to your customers and your strategy. Harvard Business Review, (November-December), 1–9. https://hbr.org/2019/11/why-are-we-here

Boal, K. B., & Hooijberg, R. (2000). Strategic leadership research: Moving on. The Leadership Quarterly, 11(4), 515–549. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S1048-9843(00)00057-6

Cesário, F., & Chambel, M. J. (2017). Linking organizational commitment and work engagement to employee performance. Knowledge and Process Management, 24(2), 152–158. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/kpm.1542

Chanana, N., & Sangeeta. (2020). Employee engagement practices during COVID-19 lockdown. Journal of Public Affairs, 21(4), e2508. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/pa.2508

Charbonnier-Voirin, A., & Roussel, P. (2012). Adaptive performance: A new scale to measure individual performance in organizations. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences / Revue Canadienne Des Sciences de l’Administration, 29(3), 280–293. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/cjas.232

Coenen, M., & Kok, R. A. W. (2014). Workplace flexibility and new product development performance: The role of telework and flexible work schedules. European Management Journal, 32(4), 564–576. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EMJ.2013.12.003

Contreras, F., Baykal, E., & Abid, G. (2020). E-leadership and teleworking in times of COVID-19 and beyond: What we know and where do we go. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 590271. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.590271

Cooper, C. D., & Kurland, N. B. (2002). Telecommuting, professional isolation, and employee development in public and private organizations. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23(4), 511–532. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/job.145

Cortellazzo, L., Bruni, E., & Zampieri, R. (2019). The role of leadership in a digitalized world: A review. Frontiers in Psychology, (10), 1-21. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01938

Darics, E. (2017). E-leadership or “how to be boss in instant messaging?” The role of nonverbal communication. International Journal of Business Communication, 57(1), 3–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/2329488416685068

Deloitte. (2014). Culture of Purpose - Building business confidence; driving growth 2014 core beliefs & culture survey. Retrieved from https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/global/Documents/About-Deloitte/gx-culture-of-purpose.pdf

Dhingra, N., Emmett, J., Samo, A., & Schaninger, Bi. (2020). Igniting individual purpose in times of crisis. Retrieved from https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/organization/our-insights/igniting-individual-purpose-in-times-of-crisis

Dorsey, D., Cortina, J., & Luchman, J. (2010). Adaptive and citizenship-related behaviors at work. In J. Farr & N. Tippins (Eds.), Handbook of Employee Selection (pp. 463–487). New York: Routledge. Retrieved from https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9781315690193-21

Emmett, J., Schrah, G., Schrimper, M., & Wood, A. (2020). COVID-19 and the employee experience: How leaders can seize the moment. Retrieved from https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/organization/our-insights/covid-19-and-the-employee-experience-how-leaders-can-seize-the-moment

Fauville, G., Luo, M., Muller Queiroz, A. C., Bailenson, J., & Hancock, J. (2021). Zoom Exhaustion & Fatigue Scale. Computers in Human Behavior Reports, 4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chbr.2021.100119

Fonner, K. L., & Roloff, M. E. (2010). Why teleworkers are more satisfied with their jobs than are office-based workers: When less contact is beneficial. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 38(4), 336–361. https://doi.org/10.1080/00909882.2010.513998

Gálvez, A., Tirado, F., & Alcaraz, J. M. (2020). “Oh! Teleworking!” Regimes of engagement and the lived experience of female Spanish teleworkers. Business Ethics: A European Review, 29(1), 180–192. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/beer.12240

Golden, T. D. (2006). Avoiding depletion in virtual work: Telework and the intervening impact of work exhaustion on commitment and turnover intentions. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 69(1), 176–187. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2006.02.003

Golden, T. D., & Veiga, J. F. (2008). The impact of superior–subordinate relationships on the commitment, job satisfaction, and performance of virtual workers. The Leadership Quarterly, 19(1), 77–88. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2007.12.009

Good, V., Hughes, D. E., & Wang, H. (2021). More than money: Establishing the importance of a sense of purpose for salespeople. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-021-00795-x

Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

Hill, P. L., Turiano, N. A., Mroczek, D. K., & Burrow, A. L. (2016). The value of a purposeful life: Sense of purpose predicts greater income and net worth. Journal of Research in Personality, 65, 38–42. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2016.07.003

Huntsman, D., Greer, A., Murphy, H., & Haynes, S. (2021). Enhancing adaptive performance in emergency response: Empowerment practices and the moderating role of tempo balance. Safety Science, 134, 105060. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2020.105060

Iriqat, R. A. M., & Khalaf, D. M. S. (2017). Using e-leadership as a strategic tool in enhancing organizational commitment of virtual teams in foreign commercial banks in North West Bank -Palestine. International Journal of Business Administration, 8(7), 25–32. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5430/ijba.v8n7p25

Jacobs, G. (2008). Constructing corporate commitment amongst remote employees. Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 13(1), 42–55. https://doi.org/10.1108/13563280810848184

Javed, B., Bashir, S., Rawwas, M. Y. A., & Arjoon, S. (2017). Islamic Work Ethic, innovative work behaviour, and adaptive performance: The mediating mechanism and an interacting effect. Current Issues in Tourism, 20(6), 647–663. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2016.1171830

Jønsson, T., & Jeppe Jeppesen, H. (2013). A closer look into the employee influence. Employee Relations, 35(1), 4–19. https://doi.org/10.1108/01425451311279384

Kaya, B., & Karatepe, O. M. (2020). Does servant leadership better explain work engagement, career satisfaction and adaptive performance than authentic leadership? International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 32(6), 2075–2095. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-05-2019-0438

Kazekami, S. (2020). Mechanisms to improve labor productivity by performing telework. Telecommunications Policy, 44(2), 101868. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.telpol.2019.101868

Kock, N., & Hadaya, P. (2018). Minimum sample size estimation in PLS-SEM: The inverse square root and gamma-exponential methods. Information Systems Journal, 28(1), 227–261. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/isj.12131

Kosine, N. R., Steger, M. F., & Duncan, S. (2008). Purpose-centered career development: A strengths-based approach to finding meaning and purpose in careers. Professional School Counseling, 12(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X0801200209

Kossek, E. E., Lautsch, B. A., & Eaton, S. C. (2006). Telecommuting, control, and boundary management: Correlates of policy use and practice, job control, and work–family effectiveness. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 68(2), 347–367. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2005.07.002

Lim, D. H., Yoo, M. H., Kim, J., & Brickell, S. A. (2017). Learning agility: the nexus between learning organization, transformative learning, and adaptive performance. Retrieved from https://newprairiepress.org/aerc/2017/papers/28

Lim, V. K. G., & Teo, T. S. H. (2000). To work or not to work at home‐An empirical investigation of factors affecting attitudes towards teleworking. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 15(6), 560–586. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940010373392

Liu, C., Van Wart, M., Kim, S., Wang, X., McCarthy, A., & Ready, D. (2020). The effects of national cultures on two technologically advanced countries: The case of e-leadership in South Korea and the United States. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 79(3), 298–329. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8500.12433

Makanjee, C. R., Hartzer, Y. F., & Uys, I. L. (2006). The effect of perceived organizational support on organizational commitment of diagnostic imaging radiographers. Radiography, 12(2), 118–126. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radi.2005.04.005

Maruyama, T., & Tietze, S. (2012). From anxiety to assurance: Concerns and outcomes of telework. Personnel Review, 41(4), 450–469. https://doi.org/10.1108/00483481211229375

Memon, M., T., R., Hwa, C., Ting, H., Chuah, F., & Cham, T. H. (2021). PLS-SEM statistical programs: A review. Journal of Applied Structural Equation Modeling, 5, i–xiv. https://doi.org/10.47263/JASEM.5(1)06

Meyer-Kalos, P. S., Roe, D., Gingerich, S., Hardy, K., Bello, I., Hrouda, D., Shapiro, D., Hayden-Lewis, K., Cao, L., Hao, X., Liang, Y., Zhong, S., & T. Mueser, K. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on coordinated specialty care (CSC) for people with first episode psychosis (FEP): Preliminary observations, and recommendations, from the United States, Israel and China. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2020.1771282

Meyer, J. P., & Allen, N. J. (1991). A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Human Resource Management Review, 1(1), 61–89. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/1053-4822(91)90011-Z

Meyer, J. P., Stanley, D. J., Herscovitch, L., & Topolnytsky, L. (2002). Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization: A meta-analysis of antecedents, correlates, and consequences. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 61(1), 20–52. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.2001.1842

Microsoft. (2021). Microsoft releases findings and considerations from one year of remote work in Work Trend Index 2021. Retrieved from https://news.microsoft.com/id-id/2021/04/30/microsoft-releases-findings-and-considerations-from-one-year-of-remote-work-in-work-trend-index-2021/

Milliman, J., Czaplewski, A. J., & Ferguson, J. (2003). Workplace spirituality and employee work attitudes. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 16(4), 426–447. https://doi.org/10.1108/09534810310484172

Morgan, R. E. (2004). Teleworking: An assessment of the benefits and challenges. European Business Review, 16(4), 344–357. https://doi.org/10.1108/09555340410699613

Nakrošienė, A., Bučiūnienė, I., & Goštautaitė, B. (2019). Working from home: Characteristics and outcomes of telework. International Journal of Manpower, 40(1), 87–101. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-07-2017-0172

Narayana, A. (2017). A critical review of organizational culture on employee performance. American Journal of Engineering and Technology Management, 2(5), 72–76. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajetm.20170205.13

Nazir, S., Shafi, A., Qun, W., Nazir, N., & Tran, Q. D. (2016). Influence of organizational rewards on organizational commitment and turnover intentions. Employee Relations, 38(4), 596–619. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-12-2014-0150

Ohana, M., & Meyer, M. (2016). Distributive justice and affective commitment in nonprofit organizations. Employee Relations, 38(6), 841–858. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-10-2015-0197

Parker, S. K., Knight, C., & Keller, A. (2020, July). Remote managers are having trust issues. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved from https://hbr.org/2020/07/remote-managers-are-having-trust-issues

Piper, H. H. M. (2004). Telework and organizational commitment: A test of the Meyer and Allen three-dimensional model of commitment [Nova Southern University]. Retrieved from https://www.proquest.com/openview/1f6c5d6b85e1a60c6928486f276118f8/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y

Prin, M., & Bartels, K. (2020). Social distancing: Implications for the operating room in the face of COVID-19. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia/Journal Canadien d’anesthésie, 67(7), 789–797. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-020-01651-2

Pulakos, E. D., Arad, S., Donovan, M. A., & Plamondon, K. E. (2000). Adaptability in the workplace: Development of a taxonomy of adaptive performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(4), 612–624). https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.85.4.612

Quinn, R. E., & Thakor, A. V. (2018). Creating a purpose-driven organization. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved from https://hbr.org/2018/07/creating-a-purpose-driven-organization

Ringle, C. M, Wende, S., & Becker, J.-M. (2015). SmartPLS 3. Boenningstedt: SmartPLS GmbH. Retrieved from http://www.smartpls.com

Ringle, Christian M, & Sarstedt, M. (2016). Gain more insight from your PLS-SEM results. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 116(9), 1865–1886. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-10-2015-0449

Robert Walter Groups. (2020). The Future of Work - Futureproofing Careers and Workforces. Retrieved from www.robertwaltersgroup.com

Roman, A. V, Van Wart, M., Wang, X., Liu, C., Kim, S., & McCarthy, A. (2019). Defining e-leadership as competence in ICT-mediated communications: An exploratory assessment. Public Administration Review, 79(6), 853–866. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12980

Ryff, C. D., & Keyes, C. L. M. (1995). The structure of psychological well-being revisited. In Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(4), 719–727. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.69.4.719

Sarkar, B. (2020). Companies roll out initiatives to keep employees’ kids engaged at home. The Economic Times. Retrieved from https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/company/corporate-trends/companies-roll-out-initiatives-to-keep-employees-kids-engaged-at-home/articleshow/75058556.cms?utm_source=contentofinterest&utm_medium=text&utm_campaign=cppst

Schaefer, S. M., Morozink Boylan, J., van Reekum, C. M., Lapate, R. C., Norris, C. J., Ryff, C. D., & Davidson, R. J. (2013). Purpose in life predicts better emotional recovery from negative stimuli. PLOS ONE, 8(11), e80329. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0080329

Shahidan, A. N. B. (2019). The Influence of Personality, Person-Environment Fit, and Work Engagement on Adaptive Performance Among Nurses in Malaysian Public Hospitals [Universiti Utara Malaysia]. Retrieved from http://etd.uum.edu.my/8068/2/s901490_02.pdf

Shmueli, G., Sarstedt, M., Hair, J. F., Cheah, J.-H., Ting, H., Vaithilingam, S., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). Predictive model assessment in PLS-SEM: Guidelines for using PLSpredict. European Journal of Marketing, 53(11), 2322–2347. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-02-2019-0189

Shoss, M. K., Witt, L. A., & Vera, D. (2012). When does adaptive performance lead to higher task performance? Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33(7), 910–924. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.780

Spence Jr, R., & Rushing, H. (2009). It’s Not What You Sell, It’s What You Stand For: Why Every Extraordinary Business is Driven by Purpose. New York: Penguin Group

Steger, M. F., Dik, B. J., & Duffy, R. D. (2012). Measuring meaningful work: The Work and Meaning Inventory (WAMI). Journal of Career Assessment, 20(3), 322–337. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072711436160

Stokols, D., Misra, S., Runnerstrom, M. G., & Hipp, J. A. (2009). Psychology in an age of ecological crisis: From personal angst to collective action. The American Psychologist, 64(3), 181–193. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014717

Thye, S. R., Vincent, A., Lawler, E. J., & Yoon, J. (2014). Relational cohesion, social commitments, and person-to-group ties: Twenty-five years of a theoretical research program. Advances in Group Processes, 31, 99–138. https://doi.org/10.1108/S0882-614520140000031008

Tietze, S., & Musson, G. (2005). Recasting the home-work relationship: A case of mutual adjustment? Organization Studies, 26(9), 1331–1352. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840605054619

Tremblay, D.-G., & Thomsin, L. (2012). Telework and mobile working: Analysis of its benefits and drawbacks. International Journal of Work Innovation, 1, 100–113. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJWI.2012.047995

Van Wart, M., Roman, A., & Pierce, S. (2016). The rise and effect of virtual modalities and functions on organizational leadership: Tracing conceptual boundaries along the e-management and e-leadership continuum. Transylvanian Review of Administrative Sciences, Special Issue. https://rtsa.ro/tras/index.php/tras/article/view/507

Van Wart, M., Roman, A., Wang, X., & Liu, C. (2017). Operationalizing the definition of e-leadership: Identifying the elements of e-leadership. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 85(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852316681446

Vega, R. P., Anderson, A. J., & Kaplan, S. A. (2015). A within-person examination of the effects of telework. Journal of Business and Psychology, 30(2), 313–323. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-014-9359-4

Wang, C. L., Indridason, T., & Saunders, M. N. K. (2010). Affective and continuance commitment in public private partnership. Employee Relations, 32(4), 396–417. https://doi.org/10.1108/01425451011051613

Wang, W., Albert, L., & Sun, Q. (2020). Employee isolation and telecommuter organizational commitment. Employee Relations: The International Journal, 42(3), 609–625. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-06-2019-0246

Wihler, A., Meurs, J. A., Wiesmann, D., Troll, L., & Blickle, G. (2017). Extraversion and adaptive performance: Integrating trait activation and socioanalytic personality theories at work. Personality and Individual Differences, 116, 133–138. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.04.034

Wojcak, E., Bajzikova, L., Sajgalikova, H., & Polakova, M. (2016). How to achieve sustainable efficiency with teleworkers: Leadership model in telework. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 229, 33–41. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.07.111

Wong, A. K. F., Kim, S. (Sam), Kim, J., & Han, H. (2021). How the COVID-19 pandemic affected hotel employee stress: Employee perceptions of occupational stressors and their consequences. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 93, 102798. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102798

Wrzesniewski, A. (2020). How to keep your sense of purpose while working remotely. Yale Insights. Retrieved from https://insights.som.yale.edu/insights/how-to-keep-your-sense-of-purpose-while-working-remotely

Yu, Y. (2020). Impact of inclusive leadership on employees’ adaptive performance. Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Education Science and Economic Development (ICESED 2019). 6–9. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2991/icesed-19.2020.74

Abstrakt

CEL: Badanie to ma na celu zbadanie, w jaki sposób postrzegane e-przywództwo i wyniki telepracy powiązane są z wydajnością adaptacyjną pracowników. Co więcej, stara się zrozumieć, czy poczucie celu i zaangażowanie organizacyjne pełnią rolę mediacyjną. Niniejsze badanie proponuje nowy model badawczy, który jest testowany empirycznie w celu przewidywania wydajności adaptacyjnej pracowników, zwłaszcza podczas pracy zdalnej z powodu pandemii COVID-19. METODYKA: Badanie ilościowe zostało przeprowadzone w sierpniu 2021 r. Odpowiedzi uzyskano od 271 telepracowników zatrudnionych w renomowanej prywatnej firmie działającej w branży finansowej w Indonezji. Dane zebrano za pomocą kwestionariusza przy użyciu skali typu Likerta, a następnie przeanalizowano przy użyciu PLS-SEM. WYNIKI: Udowodniono, że trzy czynniki poprzedzające mają bezpośredni wpływ na wydajność adaptacyjną pracowników: zaangażowanie organizacyjne, a następnie wyniki telepracy i poczucie celu. Postrzegane e-przywództwo wpływa pośrednio na wydajność adaptacyjną pracowników i jest zapośredniczone przez wyniki telepracy, zaangażowanie organizacji i poczucie celu. IMPLIKACJE: Ten pogląd sugeruje, że kierownictwo musi zadbać o wewnętrzną motywację, aby pracownicy mogli działać w organizacji. Konstrukcje te będą odgrywać znaczącą rolę i dlatego powinny być dobrze zaplanowane, dobrze wykonane i zmierzone, aby wzmocnić wydajność adaptacyjną pracowników w organizacji. Wynik modelu badawczego wskazuje na umiarkowaną siłę trafności predykcyjnej przy średnim znaczeniu predykcyjnym dla wydajności adaptacyjnej pracownika, co daje możliwość ponownego wykorzystania i rozszerzenia modelu badawczego oraz zbadania innych konstruktów. Na podstawie ustaleń kierownictwo musi skoncentrować się na zaufaniu do pracowników, motywacji zespołu i działaniach związanych z zarządzaniem doświadczeniem pracowników, aby utrzymać zaangażowanie pracowników. ORYGINALNOŚĆ I WARTOŚĆ: Jest to jedno z pierwszych badań, w których zastosowano wewnętrzną motywację jako poprzednik wydajności adaptacyjnej pracowników, wraz z postrzeganym e-przywództwem i wynikami telepracy. Korporacje będą mogły skoncentrować się na niektórych kluczowych obszarach, które, jak udowodniono, mają pozytywny wpływ na wydajność adaptacyjną pracowników.

Słowa kluczowe: e-przywództwo, telepraca, poczucie celu, zaangażowanie organizacyjne, wydajność adaptacyjna pracowników, COVID-19, motywacja wewnętrzna

Biographical notes

Ronny Tan (S.Si.) is a Senior Vice President of PT Bank Commonwealth. He earned his S.Si degree, 1998, in Physical Science from Institut Teknologi Bandung. He is now a Graduate School of Management student from Universitas Pelita Harapan, Jakarta, Indonesia.

Ferdi Antonio (Dr. dr. M.M. M.A.R.S) is an Assistant Professor at the Graduate School of Management, Universitas Pelita Harapan, Jakarta, Indonesia. He earned his Ph.D. degree, 2014, in Management from Trisakti University, Jakarta, Indonesia. He has written several articles in the Hindawi International Journal of Telemedicine and Applications, Webology, Academy of Strategic Management Journal, and Management Science Letters.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Citation (APA Style)

Tan, R., & Antonio, F. (2022). New insights on employee adaptive performance during the COVID-19 pandemic: Empirical evidence from Indonesia. Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management, and Innovation, 18(2), 175-206. https://doi.org/10.7341/20221826