Received 15 May 2019; Revised 15 July 2019, 27 September 2019, 31October 2019; Accepted 9 December 2019.

This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode).

Ghulam Abid, Assistant Professor, School of Business Adminstration, National College of Business Administration & Economics, 40-E1, Gulberg III, Lahore 54660, Pakistan, email: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.  , corresponding author.

, corresponding author.

Saira Ahmed, Institute of Business & Management, University of Engineering & Technology, Lahore, email: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Tehmina Fiaz Qazi, Assistant Professor, Institute of Business & Management, University of Engineering & Technology, Lahore, email: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Komal Sarwar, School of Business Adminstration, National College of Business Administration & Economics, 40-E1, Gulberg III, Lahore 54660, Pakistan, email: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Abstract

The psychological state in which an individual experiences a form of vitality and a sense of learning at work is known as thriving at work. Since the new millennium, empirical research is evident that thriving (employees’ sustainability) is critical for organizational sustainability. However, this human dimension of sustainability is understudied, and little is known about how individual characteristics and managers promote employee thriving at work. To address the gap, this pioneering study investigates the work context and individual differences in promoting thriving at work. The intervening mechanism of self-efficacy and prosocial motivation in the association between managerial coaching and thriving at work has been examined using a sequential mediation approach. Data has been analyzed using a Hayes’ PROCESS Model 6 (based on 1,000 bootstrap resampling) with an actual sample of 221 respondents. Our results provide support for our hypothesized model. The study finds a direct association between managerial coaching and self-efficacy. It is concluded that self-efficacy is directly related to prosocial motivation, hence enhanced employee thriving at work. It is also found that self-efficacy and prosocial motivation play a vital role in explaining the association between managerial coaching and thriving at work.

Keywords: managerial coaching, self-efficacy, prosocial motivation, thriving at work, sequential mediation

INTRODUCTION

Scholarly and corporate interest in creating sustainable organizations has been emerging for over two decades (Fritz, Lam, & Spreitzer, 2011; Kira & Van Eijnatten, 2008; Lee & Ha-Brookshire, 2017; Spreitzer, Porath, & Gibson, 2012). Sustainability states that human and other lives will be nourished on the planet forever (Ehrenfeld, 2008). Kira and Van Eijnatten (2008) stated organizational sustainability was a capacity to adjust and continue working while having a proactive and innovative approach. Organizations that exhibit efficiency, creativity, and endurance are sustainable (El Bedawy, 2015). Elkington (1997) and Spreitzer, Porath, and Gibson (2012) argued that organizations with sustainability emphasize on three dimensions concurrently, i.e. human, environmental and economic performance (also refers to three p’s, i.e. profit, planet, and people). If individuals learn the philosophy to work with natural systems rather than exploiting them, both humans and nature flourish simultaneously. Organizations that are social entities play an influential role in transforming norms of the industry by taking into account environmental and social concerns as well as harvesting the positive economic, environmental and social benefits by competing on the basis of sustainability (Hoffman & Haigh, 2010). Various research (El Bedawy, 2015; Fritz, Lam, & Spreitzer, 2011; Lee & Ha-Brookshire, 2017; Spreitzer et al., 2012) has claimed that practitioners and researchers have least focused on the human facet of sustainability compared to the other two dimensions. In this era, organizations have to operate in an environment of flux and competitiveness (Mushtaq, Abid, Sarwar, & Ahmed, 2017). Their survival, success, and growth are contingent on employees’ creativity, energy, ideas, skills and knowledge (Abid & Ahmad, 2016; Bryl, 2018; Kira & Van Eijnatten, 2008; Paterson, Luthans, & Jeung, 2014; Pereverzieva, 2019; Spreitzer, 2007). Thus, sustainability of employees (flourishing and thriving) is essential for an organization to be sustainable, and for their competitive advantage and sustainable performance (Abid, 2016; Abid, Zahra, & Ahmed, 2016b; El Bedawy, 2015; Pfeffer, 2010; Walumbwa, Muchiri, Misati, Wu, & Meiliani, 2017).

Porath, Spreitzer, Gibson, and Granett (2012) and Spreitzer, Sutcliffe, Dutton, Sonenshein, and Grant (2005) narrated the concept of thriving as a psychological, subjective experience of feeling vital and constantly learning in the workplace. Two dimensions of thriving i.e., the cognitive component (learning) and affective component (vitality), are recognized. Employees grow in the short run and adapt in the long run based on these dimensions (Spreitzer et al., 2005). Thriving workers exhibit a comparatively greater functioning and energy. In addition, Wallace, Butts, Johnson, Stevens, and Smith (2016) emphasized that thriving also delivers various other benefits and advantageous work outcomes.

A review study on the thriving at work phenomenon, carried out by Abid (2016), explored how thriving generates positive outcomes like improved, innovative work behavior, improved performance, less absenteeism, increased commitment, enhanced well-being, better psychological health, better vocal behavior, reduced turnover intention, and high work engagement. Likewise, the same outcomes relevant to thriving were also supported by theoretical argumentations in various empirical studies.

From these studies, thriving is associated with self-development (Paterson, Luthans, & Jeung, 2014), adaptability and adjustment in career (Jiang, 2017; Shan, 2016), happiness in the workplace (Qaiser, Abid, Arya, & Farooqi, 2018), life satisfaction (Flinchbaugh, Luth, & Li, 2015), job satisfaction (Abid, Khan, & Hong, 2016a), work engagement (Abid, 2016; Abid, Sajjad, Elahi, Farooqi, & Nisar, 2018; Levene, 2015; Ren, Yunlu, Shaffer, & Fodchuk, 2015; Spreitzer, Lam, & Fritz, 2010), being helpful at work (Frazier & Tupper, 2016), creativity (Abid, Zahra, & Ahmed, 2015; Carmeli & Spreitzer, 2009; Wallace et al., 2016), better performance (Elahi, Abid, Arya, & Farooqi, 2019; Paterson et al., 2014; Shan, 2016), less burnout (Porath et al., 2012), low absenteeism (Abid, 2014), lower turnover and intention to quit (Abid et al., 2015; Abid, Zahra, & Ahmed, 2016b; Ren et al., 2015). A meta-analysis conducted by Kleine, Rudolph, and Zacher (2019) found that thriving is significantly associated with job satisfaction, subjective health, organizational commitment, creative performance, attitude towards self-development, extra and in-role performances. Furthermore, they also found that it is negatively related to burnout and intention to leave the organization as well.

Although researchers have acknowledged the role of thriving at work for different industries (Gerbasi, Porath, Parker, Spreitzer, & Cross, 2015; Spreitzer & Porath, 2012), empirical studies on an individual’s thriving is insufficient in the existent literature regarding thriving (Niessen, Sonnentag, & Sach, 2012; Paterson, 2014). For example, the role of leader and manager is considered understudied while we take into account the promotion of thriving (Paterson et al., 2014). Similarly, limited knowledge is available in response to the question of how individual characteristics are linked to thriving at work (Fritz et al., 2011; Walumbwa et al., 2017). As a result, Walumbwa et al. (2017) stated that very little is known regarding the way in which personal and contextual factors on an independent and mutual basis are linked to employee thriving.

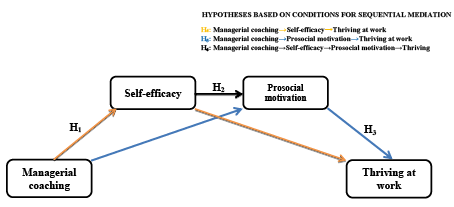

A socially-rooted model of thriving was presented by Spreitzer and her research companions in 2005. They suggested that learning and vitality are promoted through contextual aspects (managerial coaching and prosocial motivation) and individual differences (i.e., self-efficacy). The definition of managerial coaching refers to “the actions of the manager or leader who acts as a coach and facilitates learning in the workplace environment through specific behaviors that enable the employee to learn and develop” (Ellinger, Ellinger, & Keller, 2003). The focus of managerial coaching revolves around the activities that facilitate a relationship among superiors and subordinates, thereby helping in performance improvement, motivating subordinates to face the upcoming challenging tasks, and promoting the confidence to take action (Pousa & Mathieu, 2015). Self-efficacy is defined as an individual’s belief about his/her capability to perform any task (Bandura, 1977). This specific investigating study advocates that, for people in the workplace, self-efficacy can play the role of a catalyst in enhancing prosocial motivation because they possess a feeling of competency and ability to carry out their work-related tasks. They exhibit a facilitating behavior towards their colleagues for the successful accomplishment of goals. The definition of prosocial motivation is explained as the aspiration to disburse effort in order to benefit others (Grant & Sumanth, 2009).

Therefore, this study incorporates a twofold objective: investigating the predictors of thriving at work (self-efficacy, managerial coaching, and prosocial motivation) and exploring the underlying mechanism through which managerial coaching impacts thriving at work via sequential mediation of self-efficacy and prosocial motivation. The sequential mediating mechanism, through which managerial coaching impacts thriving at work, has not been addressed by scholars to the best of our knowledge.

To attain the overall development and growth of the organization, the proficiency of workers to develop at work is essential (Abid et al., 2016b; Paterson et al., 2014). Therefore, the significance of this study can be advocated for both fields, i.e., for academia and for industry as well. The curiosity regarding investigation of employee thriving in the workplace prevails among researchers. They are fascinated to inspect the backgrounds and mechanism of employee thriving (Elahi et al., 2018; Paterson et al., 2014; Qaiser et al., 2018), most specifically the individual differences and contextual factors that promote thriving.

In the same manner, the understanding of key constructs through which firms can achieve favorable outcomes from employees can be considered as a matter of interest for practitioners and managers (Abid, Contreras, Ahmed, & Qazi, 2019). Thoughtful attention must be directed towards the proxy outcomes of the managerial coaching process by managers. In this context, the findings of this study provide managers with a strong rationale for employing coaching practices in their organizations and industrial practices. The consideration of managerial coaching as a predictor of self-efficacy, thriving at work and prosocial motivation, is advocated by the results of empirical evidence and after assessing its growing need in the industry when the problems are unstructured and human capital is considered as a competitive advantage (Bryl, 2018). To attain the motives of the said constructs, management needs to stress the significance of managerial coaching, which may not only coach their subordinates but also encourage them to help other colleagues in the workplace, ultimately achieving its realistic insights in work settings.

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND AND HYPOTHESES

Thriving at work

“Thriving” has gained unprecedented attention from divergent domains by researchers and practitioners (e.g., youth development and work), resulting in a diverse knowledge and a lack of consensus on conceptual and operational definitions that underpin the concept (Brown, Arnold, Fletcher, & Standage, 2017). The term ‘thrive’ denotes the ability of an individual for growth and flourishing (Merriam-Webster Dictionary, 2019). In the management literature, this promising concept is socially embedded and is elaborated as “a psychological state [in] which individuals experience both a sense of vitality and a sense of learning at work” (Spreitzer et al., 2005) and the said state is modified over time (Niessen et al., 2012). Vitality (or vigor) is the subjective experience of an individual related to energy (Shirom, 2004). In contrast, a cognitive element of thriving is known as learning, which relates to growing through attaining and exploiting the skills and knowledge in a work setting.

According to Spreitzer et al. (2005) and Porath et al. (2012), the experience regarding thriving is an intersection of both components – vitality and learning. An individual is not thriving if lower energy levels are felt, but he or she has acquired any novel skill. So, thriving at work can not be achieved if burnout results from knowledge acquisition. In contrast, if the skill or knowledge acquisition is not accompanied by an experience of vitality, then an individual is also not thriving because of deficit thrust regarding workplace development. Hence, a psychological condition in which the feeling of being energetic, and a state of enhancing knowledge and skill is achieved, is known as thriving.

The two elements work as complementary forces, as feeling more energized results in positive feelings that motivate one towards self-development, which includes learning both in and out of the workplace. When individuals thrive at work, they feel energetic, exhibit high levels of psychological functioning (O’Leary & Ickovics, 1995; Porath et al., 2012), experience progress and thrust at work (Carmeli & Spreitzer, 2009). Thriving individuals are generally unsatisfied with the status quo because they are self-learners who vigorously find ways to keep on learning and growing (Niessen et al., 2012), and navigate their own path for sustaining their development (Spreitzer et al., 2005). Therefore, these individuals want to prolong or renew this positive state.

Thriving at work plays an essential role in mitigating absenteeism, which can be one of the resultants from workplace stressors like burnout, incivility, depression, harassment, and costs organizations around $84 billion per annum in lost productivity across 14 different job types (Forbes, 2013; Gallup, 2013). Also, the time spent on activities regarding work-related factors has a significant influence on employee health (Beehr & Newman, 1978). The health of any individual is crucial for both the organization and society at large. Thriving at work is associated with physical health likewise, and the risk of heart disease is more threatening to employees who feel inadequate growth at work (Alfredsson, Spetz, & Theorell, 1985).

Managerial coaching, self-efficacy, and prosocial motivation

In this modern era, organizational development and the manager-subordinate relationship is significant for an organization’s success. Hagen (2012) stated that coaching could serve as a tool for a positive manager-subordinate relationship and also promote organizational development. Executive coaching (Grant, 2014), coaching leadership (Beattie, Kim, Hagen, Egan, Ellinger, & Hamlin, 2014) and peer coaching (Parker, Kram, & Hill, 2014) are a few of the well-known types in the coaching literature. It is defined as “the actions of the manager or leader who acts as a coach and facilitates learning in the workplace environment through specific behaviors that enable the employee to learn and develop” (Ellinger, Ellinger, & Keller, 2003). Whereas, managerial coaching or hierarchical coaching (Beattie et al., 2014) integrates the two well-known constructs of i.e. coaching and leadership and it focuses on the practices in which managers use their leadership abilities in order to motivate and enhance the performance of their subordinates (Ellinger et al., 2003). It is an emerging and very important concept in the field of management, and a lot of empirical work has been done to find out the significance of managerial coaching (Baron & Morin, 2010; Gordon Bar & St. Rosh-Ha’Ayin, 2014; Moen & Allgood, 2009). It is considered as the core activity for managers in attaining the optimal performance of their subordinates (Evered & Selman, 1989; Hamlin, Ellinger, & Beattie, 2006). Managerial coaching is also referred to as a strategy that can dramatically improve the competitiveness of the firm as it stimulates a positive relationship among managers and subordinates (Hagen, 2012). It also inspires subordinates and helps them to grow (Kim et al., 2014). Literature on managerial coaching has reported many beneficial outcomes (Zhang, Jensen, & Mann, 1997) including performance improvement (Ellinger et al., 2003; Liu & Batt, 2010), employee learning (Hagen et al., 2012), commitment to quality (Elmadag et al., 2008), job satisfaction (Kim, 2014), motivation (Gilley, Gilley, & Kouider, 2010) and self-efficacy (Pousa & Mathieu, 2015). In support of earlier work, this study proposes that managerial coaching is significantly linked to an employee’s self-efficacy.

Self-efficacy is the “individual’s belief that he or she is capable of performing a task” (Bandura, 1977). Self-efficacy leads to greater confidence and perseverance while confronting complications. It is derived from the social cognitive theory (Pousa & Mathieu, 2015; Zieba & Golik, 2018). Social cognitive theory explains “how people acquired and regulated their behaviors in order to cope with circumstances and achieve outcomes” (Bandura, 1977). Scholars have mentioned that the beliefs of personal efficacy of individuals are based on the four primary sources: 1) vicarious experience, 2) verbal persuasion, 3) past performance accomplishment, and 4) physiological states (Bandura, 1977; Wood & Bandura, 1989). Self-efficacy or personal efficacy is “a comprehensive summary or judgment of the perceived capability of performing a task” (Gist & Mitchell 1992, p. 184). Managerial coaching focuses on the activities that facilitate a relationship among superiors and subordinates, thereby helping performance improvement (Hagen, 2012), motivating subordinates to face the upcoming challenging tasks, and boosting confidence to take action (Pousa & Mathieu, 2015). Therefore, it is hypothesized that managerial coaching also enhances the sense of perceived self-efficacy in employees. Based on the above arguments, this study hypothesizes that:

H1: Managerial coaching is positively related to self-efficacy.

Since the association between managerial coaching and thriving at work was established empirically initially (Abid et al., 2019), we do not test it as a hypothesis. However, we do study the association between managerial coaching and thriving at work to complete the development of our sequential mediation model.

How does self-efficacy facilitate the sense of prosocial motivation in a work setting? To answer this question, this study further proposes that the feeling of self-efficacy may promote prosocial motivation of employees at work. The self-efficacy construct has links with several work-related outcomes such as performance, stress, job attitudes (Bandura, 1997; Stajkovic & Luthans, 1998). This study suggests that self-efficacy may fuel prosocial motivation at work because when individuals feel that they are competent and capable of doing their work, then they also try to help their peers with tasks and hence this has an impact on their lives. Self-efficacy explains what the beliefs of individuals are, how they think and act (Bandura, 1977), and activate their motivation (Pousa & Mathieu, 2015; Wood & Bandura, 1989). When employees experience self-efficacy, it can directly activate the positive moods that help them to engage in extra-role behavior and prosocial behavior. Prosocial motivation is a construct that is distinct from self-interested motivation, as it is the desire of an individual to help, defend and encourage the welfare of “others” (Grant & Berry, 2011). Recent revisions explored that it is allied with job performance and core self-evaluations (Judge & Bono, 2001), creativity (Grant & Berry, 2011), and other similar variables (Grant & Sumanth, 2009). Here, the current study proposes that when an individual feels that he or she is capable of performing his task, then he or she is in a better position to help others in their task. On the basis of the above discussion, it is hypothesized that:

H2: Self-efficacy is positively related to prosocial motivation.

Prosocial motivation and thriving at work

Prosocial motivation is defined as “the desire to expend effort in order to benefit other people” (Grant & Sumanth, 2009). Gebaeur et al. (2008) identify two possible underlying motives for prosocial behavior: such as being helpful for personal pleasure or “pleasure-based prosocial motivation” and being helpful in order to conform to generally accepted social standards or “pressure-based prosocial motivation.” The distinction between the two types of prosocial motivation is that one can see it as intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, where pleasure-based motivation is intrinsically derived, whereas pressure-based motivation is extrinsically driven. The literature suggests that prosocial behavior, whether derived from intrinsic or extrinsic motivation, is linked to subjective welfare and, more precisely, to an individual’s feeling of relatedness (Deci & Ryan, 1985; Maslow, 1954, Organ & Ryan, 1995). Prosocial behavior has been linked to persistence, higher productivity, and better performance in employees (Grant, 2008). A prosocial personality has been found to be one of the pre-requisites for extra-role behavior (i.e., OCB) (Borman, Penner, Allen, & Motowidlo, 2001). Rioux & Penner (2001) present a strong case for prosocial motivation being a critical factor in organizational citizenship behavior, which benefits other individuals (as opposed to the organization as a whole).

Scholars have demonstrated the benefits of organizational citizenship behavior. They include, among other things, an increase in trust between coworkers and a work environment that lends itself to the growth and development of individuals (Cameron, 2012; Dudley & Cortina, 2008). Prosocial behavior is also paramount in creating a forgiveness climate in the workplace, which increases employee perception of organizational justice, encourages conflict management through individual engagement, and improves trust between coworkers (Fehr & Gelfand, 2012). Prosocial motivation also helps to mitigate the effects of incivility in the workplace (Liu, Steve Chi, Friedman, & Tsai, 2009), which, as theorized in the previous section, is related to thriving in the workplace. Furthermore, prosocial behavior helps in both individual and organizational growth because it is reciprocated by coworkers and results in a more efficient fulfillment of goals (Zhu & Akhtar, 2014). Crant and Bateman (2000) identified prosocial assertiveness as one of the personality traits of charismatic leaders. In other words, both leaders and followers experience growth as a result of prosocial behavior. Prosocial motivation leads to prosocial behavior through which employees develop stronger interpersonal connections in the workplace, making their work-life more satisfying (Grant & Rothbard, 2013). Grant and Berry (2011) instituted that prosocial motivation enabled employees to be more creative. Drawing on the above, prosocial motivation contributes to thriving in several ways. For instance, pleasure-based or intrinsic prosocial motivation leads to feelings of personal satisfaction i.e. increased vitality, both intrinsic and extrinsic prosocial motivation help in growth and development as the behavior is reciprocated by co-workers leading to the faster accomplishment of goals (individual and organizational), and prosocial behavior contributes towards fostering a work environment that is based on trust and close interpersonal relationships (relatedness).

Furthermore, the consideration provided to prosocial motivation is regarded as an attractive phenomenon (Hu & Liden, 2015). The facilitating behavior of an employee stimulates the same act in the other employees accordingly. Similarly, the employee is expected to become learning-oriented, which is vital in attaining a shield of prosocial motivation as an emphasing factor, and ultimately promotes thriving at work (Abid et al., 2018; Nawaz, Abid, Arya, Bhatti, & Farooqi, 2018). Therefore, based on the above discussion, it can be theorized that prosocial motivation leads to an individual thriving in the workplace.

H3: Prosocial motivation is positively related to thriving at work.

Sequential mediation of self-efficacy and prosocial motivation

Lastly, the current study proposes that self-efficacy and prosocial motivation sequentially mediate the link between managerial coaching and thriving at work. Thriving is a psychosomatic process and a mutual experience of cognition (learning) and affect (vitality) (Spreitzer et al., 2005). Managerial coaching, self-efficacy, and prosocial motivation are all essential antecedents that foster thriving. Managerial coaching is crucial to motivating employees and contributing to their growth and development (Gilley et al., 2010). With the help of a coaching role, managers assist employees in solving complicated problems, building confidence (Pousa & Mathieu, 2015), and helping achieve task performance, thereby, increasing self-efficacy among those employees as self-efficacy is the perceived capability of performing tasks. Figure 1 presents the theoretical model.

H4: Self-efficacy mediates the relationship between managerial coaching and thriving at work.

H5: Prosocial motivation mediates the relationship between managerial coaching and thriving at work.

H6: Self-efficacy and prosocial motivation mediates the relationship between managerial coaching and thriving at work.

Figure 1. Theoretical model

When employees experience self-efficacy, it can directly activate the positive moods that help them to engross in extra-role behavior and prosocial behavior. Prosocial motivation is the desire of an individual to support, protect, and promote the well-being of “others” (Grant & Berry, 2011). When an individual feels that he or she is capable of performing his task, then he or she is in a better position to help others with the intent to build long- term relationships. Moreover, pleasure-based or intrinsic prosocial motivation leads to feelings of personal satisfaction i.e. increased vitality. Both intrinsic and extrinsic prosocial motivation help in growth and development as the behavior is reciprocated by co-workers, leading to the faster accomplishment of goals (individual and organizational). Prosocial behavior contributes to fostering a work environment that is based on trust and close interpersonal relationships (relatedness) and can enhance vitality and boost learning at work (Abid et al., 2016b). Therefore, on the basis of the above discussion, it is theorized that prosocial motivation leads to an individual thriving in the workplace.

METHODS

Sample

The present study focuses on the variables that predict an employee’s thriving. The concept of thriving is not context-specific and prevails in different industries and various types of occupations. Therefore, a heterogeneous sample has been collected purposively (purposive sampling) to keep the scope more comprehensive. The study sample (221) from which data was collected included employees working in both public and diverse private industries as data controllers, coordinators, teachers, and administrative staff. A structured questionnaire was utilized as a data-gathering technique to minimize the interference of the researcher. 41 (18.6%) female respondents and 180 (81.4%) male respondents took part in the study. The majority were married 134 (60.6 %). The age was classified (years denoted as yrs) as 20yrs – 29yrs, 30yrs – 39yrs, 40yrs – 49yrs, and above 49yrs for which the number of respondents was 89, 76, 47, and 9 respectively with an average age of 33.8 yrs. The working tenure of the majority of participants was less than 5yrs, with an average of 8yrs. The sample consists of employees whose average education was 15 years (Table 1).

Table 1. Sample characteristics

|

Control Variables |

Frequency |

Percent |

|

|

Gender |

Female |

41 |

18.6 |

|

Male |

180 |

81.4 |

|

|

Marital status |

Single |

85 |

38.5 |

|

Married |

134 |

60.6 |

|

|

Divorced |

2 |

0.9 |

|

|

Age |

20yrs – 29yrs |

89 |

40.3 |

|

30yrs – 39yrs |

76 |

34.4 |

|

|

40yrs – 49yrs |

47 |

21.3 |

|

|

above 49yrs |

9 |

4.1 |

|

|

Working tenure |

less than 5 yrs |

100 |

45.2 |

|

5yrs – 9yrs |

46 |

20.8 |

|

|

10yrs – 14yrs |

25 |

11.3 |

|

|

15yrs – 19yrs |

13 |

5.9 |

|

|

20yrs – 24yrs |

8 |

3.6 |

|

|

25yrs – 29yrs |

13 |

5.9 |

|

|

above 29yrs |

5 |

2.3 |

|

|

Missing |

11 |

5 |

|

Measures

A five-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree) was used for all mentioned study variables (managerial coaching, self-efficacy, prosocial motivation, and thriving at work).

Managerial coaching

Coaching is defined as an ongoing, face-to-face process on influencing behavior by which the manager and employee collaborate to assist in achieving increased job knowledge, improved skills in carrying out job responsibilities, a higher level of job satisfaction, a stronger, more positive working relationship, and opportunities for personal and professional growth (Allenbaugh, 1983). Managerial coaching is measured through 5 of the 7 items developed and validated in Ellinger et al.’s (2003) research. A sample item from this scale was “My manager sets expectations with employees and communicates the importance of those expectations to the broaden goals of the company.”

Self-efficacy

Self-efficacy is “the individual’s perceptual judgment or belief of how well one can execute courses of action required to deal with prospective situations” (Bandura, 1982). Chen, Gully, and Eden’s (2001) scale, which consists of 8 items, was used to assess the self-efficacy in this study. A sample item from this scale was, “I will be able to achieve most of the goals that I have set for myself.”

Prosocial motivation

It refers to “the desire to expend effort in order to benefit other people” (Grant & Sumanth, 2009). Prosocial motivation was assessed using a 5-items scale developed by Grant and Sumanth (2009). A sample item from this scale was, “It is important to me to have the opportunity to use my abilities to benefit others.”

Thriving at work

Thriving is a psychological state in which employees experience both a sense of vitality and learning at work (Spreitzer et al., 2005). A 10-items scale developed by Porath et al. (2012) was adopted to capture both the dimensions of thriving at work. A sample item from this scale was, “I find myself learning often.”

Control variables

The study controls the demographics that might influence the results: gender, age, tenure, and marital status. Age relates to the vitality and learning factors of thriving. It is stated that work might be exhausting for older employees and diminish their vitality (Niessen et al., 2012; Uchino, Berg, Smith, Pearce, & Skinner, 2006). Moreover, age is also negatively associated with the willingness and ability to learn. Gender and tenure at work are also critical (Galup, Klein, & Jiang, 2008). A meta-analysis suggests that women tend to be exhausted and less vital at work compared to men (Purvanova & Muros, 2010). Finally, workers who worked fewer years might have a higher capacity for learning than those who worked for a more extended period in one company.

Analytical strategy

The theoretical model was tested in two stages. At first, the measurement model was examined by forming parcels of items (Hall et al., 1999) as well as without parcels. The current study tested and compared the measurement model with other alternate models with the traditional Chi-square/degree of freedom, goodness-of-fit index (GFI), comparative fit index (CFI), non-normed fit index (NNFI), incremental fit index (IFI), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) (Browne & Cudeck, 1993; Hooper, Coughlan & Mullen, 2008; Hoyle, 1995; Hu & Bentler, 1999; Marsh, Balla, & Hau, 1996). The acceptable values for SRMR should be <0.08 and >0.90 for all other indexes. Moreover, the value higher than 0.80 is considered a permissible fit for CFI and IFI. In the second step, the hypothesized model is tested with the help of Hayes’ process (Hayes, 2012).

A total of six parcels of all the items pertaining to three study constructs has been studied. A parcel refers to an “aggregate-level factor comprising of computing two or more items” (Bakker, Tims, & Derks, 2012). The psychometric advantage of the measurement model created through parcels is that the results are more reliable (Little, Cunningham, Shahar, & Widaman, 2002). Parceling helps in eliminating a Type I error in the item correlations because it takes less iteration to converge, minimizing the chance of model miss-specification, thereby, resulting in more stable solutions (Bakker et al., 2012). Therefore, this technique is advisable instead of using many items as indicators of the construct. Parcels of items for “self-efficacy,” “thriving at work,” and “prosocial motivation” were formed. These three constructs were included in the measurement model as latent factors with two parcels each. Self-efficacy was specified with two parcels comprising of four items each and five items for both of the parcels of thriving at work. Moreover, prosocial motivation was specified with two parcels, including two and three items, respectively.

The current study tested the sequential indirect effect of self-efficacy and prosocial motivation in the relationship between managerial coaching and thriving at work by mean of bootstrapping. The bootstrap is a “statistical resampling technique that estimates the parameters of the model and their standard errors strictly from the sample” (Preacher & Hayes, 2008). This technique calculates precise and correct confidence intervals of indirect effects, as compared to the causal steps strategy of Baron and Kenny (1986). The reason for this is that it does not assume normal sampling distribution (Preacher & Hayes, 2008).

RESULTS

The current study examined the measurement model through parcels tapping the four study variables. The proposed hypothesize four factor measurement model (with parcels) revealed an adequate fit to data (χ2(35)=133.22, GFI=0.90, CFI=0.90, NFI=0.88, IFI=0.91, RMR=0.04), which is better than the alternate one factor model (χ2(350)=1339.32, GFI=0.67, CFI=0.59, NFI=0.52, IFI=0.59, RMR=0.08), two factor model (MC+SE,PM+T: χ2(349)=1295.64, GFI=0.67, CFI=0.60, NFI=0.53, IFI=0.61, RMR=0.08), and three factor model (MC,SE+PM,T: χ2(347)=1122.53, GFI=0.71, CFI=0.67, NFI=0.59, IFI=0.68, RMR=0.08. Moreover, our four factor measurement model (without parcels) also revealed an adequate fit to data (χ2(331)=740.37, CFI=0.83, TLI=0.80, IFI=0.83, RMR=0.06, RMSEA=0.08) as compared to other alternate models.

Robustness check

Given that scholars have identified some limitations of parceling, we also conducted a robustness check without item parcels. Results indicate that the full measurement model has a better model fit indices (χ2(153)=362.40, GFI=0.85, CFI=0.88, TLI=0.80, IFI=0.85, RMR=0.06), RMSEA=0.08) compared with alternative one factor, two factors, and three-factor models.

Table 2 exhibits correlations and descriptive analysis among variables. Consistent with the hypotheses, the correlations show that managerial coaching is positively linked with self-efficacy (r=0.46, p<0.01), prosocial motivation (r=0.40, p<0.01), and thriving at work (r=0.41, p<0.01). Also, self-efficacy is positively linked to prosocial motivation (r=0.63, p<0.01), and thriving at work (r=0.68, p<0.01). Moreover, results also show a positive relationship between prosocial motivation and thriving at work (r= 0.57, p<0.01).

Table 2. Mean, sd and correlation matrix

|

Variables |

Mean |

SD |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

1. Age |

33.85 |

8.65 |

1 |

|||||

|

2. Education |

15.12 |

2.19 |

-0.16* |

1 |

||||

|

3. Tenure |

8.58 |

8.25 |

0.71** |

-0.30** |

1 |

|||

|

4. Managerial coaching |

3.75 |

0.67 |

0.03 |

0.02 |

0.03 |

1 |

||

|

5. Self-efficacy |

3.89 |

0.50 |

-0.11 |

0.04 |

-0.10 |

0.46** |

1 |

|

|

6. Prosocial motivation |

4.03 |

0.60 |

-0.13 |

0.10 |

-0.13 |

0.40** |

0.63** |

1 |

|

7. Thriving at work |

3.73 |

0.67 |

-0.11 |

-0.02 |

-0.04 |

0.41** |

0.68** |

0.57** |

Notte: ** p < 0.01; * p < 0.05.

To test the model and hypotheses further, Hayes’ process (Hayes, 2012) has been used, which, according to Field (2013), is by far the best way to tackle moderation and mediation. According to the conceptual framework, thriving mediates the relationship between curiosity and constructive voice behavior, and this relationship is moderated in the presence of incivility in the environment; thus a Hayes process model 6 has been used to test the propositions on a sample of 221 with parameter estimates based on 1,000 bootstrap samples. The bias-corrected and accelerated 90% confidence intervals were then examined.

The results from output Table 3 show that the model is a good fit at p=0.00<.05 and that managerial coaching significantly predicts self-efficacy, β=0.35, 90% CI [0.28, 0.43], t=7.75, p=0.00. The R2 value tells that managerial coaching explains 22% of the variance in self-efficacy. As the β is positive, it means the relationship is positive: as managerial coaching increases, so does self-efficacy.

Table 3. Outcome: Self-efficacy

|

Model summary |

|||||||

|

R |

R-sq |

MSE |

F |

df1 |

df2 |

p |

|

|

0.46 |

0.22 |

0.20 |

60.03 |

1.00 |

219.00 |

0.00 |

|

|

Model |

|||||||

|

Coeff |

Se |

t |

p |

LLCI |

ULCI |

||

|

Constant |

2.58 |

0.17 |

14.99 |

0.00 |

2.30 |

2.9 |

|

|

Managerial coaching |

0.35 |

0.05 |

7.75 |

0.00 |

0.28 |

0.43 |

|

Output Table 4 shows the results of regressing prosocial motivation with self-efficacy and managerial coaching. Self-efficacy significantly predicts prosocial motivation, with a total effect of β=0.68, 90% CI [0.56, 0.80], t=9.59, p=0.00; managerial coaching also significantly predicts prosocial motivation, of β=0.12, 90% CI [0.03, 0.21], t=2.26, p=0.03. The R2 value tells that the model explains 41 % of the variance in prosocial motivation. These relationships are in the predicted direction.

Table 4. Outcome: Prosocial motivation

|

Model summary |

|||||||

|

R |

R-sq |

MSE |

F |

df1 |

df2 |

p |

|

|

0.64 |

0.41 |

0.22 |

74.57 |

2.00 |

218.00 |

0.00 |

|

|

Model |

|||||||

|

Coeff |

Se |

t |

P |

LLCI |

ULCI |

||

|

Constant |

0.94 |

0.26 |

3.65 |

0.00 |

0.51 |

1.36 |

|

|

Self-efficacy |

0.68 |

0.07 |

9.59 |

0.00 |

0.56 |

0.80 |

|

|

Managerial coaching |

0.12 |

0.05 |

2.26 |

0.03 |

0.03 |

0.21 |

|

Output Table 5 shows the results of regressing thriving at work with self-efficacy, prosocial motivation, and managerial coaching. Self-efficacy significantly predicts thriving at work, with a total effect of β=0.51, 90% CI [0.40, 0.62], t=7.67, p=0.00; prosocial motivation also significantly predicts thriving at work, of β=0.19, 90% CI [0.10, 0.28], t=3.56, p = 0.001. Moreover, managerial coaching also significantly predicts thriving at work, of β=0.08, 90% CI [0.01, 0.15], t=1.78, p=0.08. The R2 value tells that the model explains 50% of the variance in thriving at work. These relationships are in the predicted direction.

Table 5. Outcome: Thriving at work

|

Model summary |

|||||||

|

R |

R-sq |

MSE |

F |

df1 |

df2 |

p |

|

|

0.71 |

0.50 |

0.13 |

72.83 |

3.00 |

217.00 |

0.00 |

|

|

Model |

|||||||

|

Coeff |

Se |

T |

P |

LLCI |

ULCI |

||

|

Constant |

0.94 |

0.21 |

4.55 |

0.00 |

0.60 |

1.28 |

|

|

Self-efficacy |

0.51 |

0.07 |

7.67 |

0.00 |

0.40 |

0.62 |

|

|

Prosocial motivation |

0.19 |

0.05 |

3.56 |

0.00 |

0.10 |

0.28 |

|

|

Managerial coaching |

0.08 |

0.04 |

1.78 |

0.08 |

0.01 |

0.15 |

|

The output of Table 6 is the most important part of the output because it displays the results for the indirect effect of managerial coaching on thriving at work (i.e., the effect via relationships of self-efficacy and prosocial motivation). The result shows the indirect effects (coefficients) are significant for all the paths (hypotheses H4, β=0.18, 90% BCa CI[0.12 - 0.25]; hypotheses H5, β=0.02, 90% BCa CI[0.01 - 0.05]; hypothesis H6, β=0.05, 90% BCa CI[0.02 - 0.09]), as well as bootstrapped standard error and confidence interval. The Boot CI [LLCI, ULCI] does not contain zero, which indicates the presence of indirect effects. Hence hypotheses H4, H5, and H6 are supported. On the other side, self-efficacy and prosocial motivation mediates the relationship between managerial coaching and thriving at work. Employees are most probably thriving when they are prosocially motivated, feel self-efficacy, and receive managerial coaching at work.

Table 6. Indirect effect of managerial coaching on thriving at work

|

Direct effect of X on Y |

Effect |

Se |

T |

p |

LLCI |

ULCI |

|

|

0.08 |

0.04 |

1.78 |

0.08 |

0.01 |

0.15 |

||

|

Indirect effect(s) of managerial coaching on thriving |

|||||||

|

Effect |

Boot SE |

BootLLCI |

BootULCI |

||||

|

Total |

0.25 |

0.05 |

0.17 |

0.34 |

|||

|

H4: Coaching →Efficacy→Thriving |

0.18 |

0.04 |

0.12 |

0.25 |

|||

|

H6: Coaching→Efficacy→Motivation→Thriving |

0.05 |

0.02 |

0.02 |

0.09 |

|||

|

H5: Coaching→Motivation→Thriving |

0.02 |

0.01 |

0.01 |

0.05 |

|||

DISCUSSION

The current study investigated the serial-mediated relationship between managerial coaching and thriving at work via self-efficacy and prosocial motivation. The findings are based on a diverse sample and reinforced the serial-mediated effect of managerial coaching on thriving via self-efficacy and prosocial motivation.

Our research attempt also encompasses the emerging literature on thriving at work in several means. Mainly, outcomes validate that managerial coaching increases the self-efficacy of employees. The theme behind the coaching is to enhance the employee’s self-efficacy related to the specific work activity so that they can perform tasks effectively and efficiently. The outcomes are aligned with the findings of Pousa and Mathieu (2015). The efficacy among employees directly activates positive moods. These moods help them to engage in extra-role behavior and prosocial behavior, creating and enabling a work context in which employees experience a sense of vitality and learning. This study is a contribution to dig out the awareness related to the affiliation between prosocial motivation and thriving and deliver a comprehensive supplementary analysis of the procedure behind the optimistic effects of managerial coaching. Attention to thriving as an outcome of managerial coaching is imperative, seeing that thriving is key in extenuating the adverse effects (Abid et al., 2015; Abid et al., 2016b), enhancing the individual and organizational performance (Porath et al., 2012) and facilitating employees to improve the navigation of their careers in tempestuous modern times (De Janasz, Sullivan, & Whiting, 2003). This study demonstrates that managerial coaching, self-efficacy, and prosocial motivation are to be considered expressive for evolving intellect of thriving in the workplace. The said consequences are aligned with foregoing research outcomes (Paterson et al., 2014) indicating that vigilant associations with an administrator are critical for nurturing individual learning and the added expansion of studies signifying the rank of self-efficacy and prosocial motivation in growing a positive energy at work (efficacy and motivation to energy). Thus, this study encompasses this mark of conjecturing about the procedure by which employees can achieve self-confidence, be prosocially motivated, and thereby experience thriving in the workplace.

Secondly, in non-western countries, managerial coaching stimulates better thriving for employees. This judgment has imperative theoretical insinuation for thriving research, as it reacts to modern appeals for further research on the antecedents of thriving (Paterson, 2014) and spreads research on thriving by examining how individuals thrive in a South Asian country.

CONCLUSION

The present study has quite a few boundaries. Data collection was at one point in time through self-reported questionnaires from the same source. Therefore the results can be inflated by common method variance (Podsakoff, Mackenzie, & Podsakoff, 2012). The biases may have confounded the results and may restrain the assurance of conclusions about the causality. Even though efforts (methodological measures) are made to minimize same-source bias in the current study, the non-availability of autoregressive research design (which directs the data collection of all study variables at all points in time) appeals for thoughtfulness concerning the causal ordering of the study’s variables. Future researchers can strengthen the methodology as well. For example, by collecting data on the variables at all points in time in order to examine whether managerial coaching engenders self-efficacy, self-efficacy prosocially motivates employees, and thereby prosocial motivation promotes thriving at work. Therefore, there is a need to embrace a longitudinal approach or experimental methods to authenticate the causal relationships. Future researchers should also employ multilevel data to minimize common method bias.

Moreover, for collecting the information regarding the existence of managerial coaching, self-efficacy, prosocial motivation, and thriving from other sources, a mono-method bias can be avoided if different measurement strategies are employed. Additionally, data have been analyzed by utilizing a Hayes PROCESS (2012). Ironically, it is considered an authentic and reliable method for analyzing sequential mediation. Also, future studies can be better directed to conduct a unique technique, Structural Equation Modelling (SEM), for analysis purposes. The present research attempt has only explored two sequential mediators for the managerial coaching and thriving association. It is rational to presume that other mediators may be present to clarify the mechanisms underlying this association, as demonstrated in results that self-efficacy and prosocial motivation plays a role of partial, instead of full, mediators. Future studies need to incorporate other mediators in the connection between managerial coaching and thriving and probe the strengths of these mediating variables. Such mediators may include; perceived organizational support, trust, grit, compassion at work, and other individual-level variables.

The above-mentioned limitations are countered with the help of the study’s strengths. First, the current research offers a relatively additional understanding of how to boost thriving at work. This study must be considered one of the first to probe the sequential mediation mechanism for the effect of managerial coaching on thriving. With the help of proposing self-efficacy and prosocial motivation to investigate the underlying process, this research study identified a new antecedent of thriving at work that has not been examined previously. Second, moving beyond existing studies, this research is the earliest to explore the connotation between managerial coaching and thriving at work among working adults, rather than focusing on students. In the current study, a representative sample from an extensive array of occupations in various private and public organizations has been utilized, which assured the generalizability of the finding, particularly among South Asian workers.

References

Abid, G. (2014). Promoting thriving at work through job characteristics for performance and absenteeism. Unpublished Master of Philosophy dissertation. Lahore, Pakistan: National College of Business Administration & Economics.

Abid, G. (2016). How does thriving matter at workplace. International Journal of Economics and Empirical Research, 4(10), 521-527.

Abid, G., & Ahmad, A. (2016). Multifacetedness of thriving: Its cognitive, affective, and behavioral dimensions. International Journal of Information, Business and Management, 8(3), 121-130. https://ssrn.com/abstract=2774601

Abid, G., Contreras, F., Ahmed, S., & Qazi, T. (2019). Contextual factors and organizational commitment: Examining the mediating role of thriving at work. Sustainability, 11(17), 4686. http://doi.org/10.3390/su11174686

Abid, G., Khan, B., & Hong, M. C. W. (2016a, January). Thriving at work: How fairness perception matters for employee’s thriving and job satisfaction. Academy of Management Proceedings, 2016(1), 11948. https://doi.org/10.5465/ambpp.2016.11948abstract

Abid, G., Sajjad, I., Elahi, N. S., Farooqi, S., & Nisar, A. (2018). The influence of prosocial motivation and civility on work engagement: The mediating role of thriving at work. Cogent-Business & Management, 5(1), 1-19. http://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2018.1493712

Abid, G., Zahra, I., & Ahmed, A. (2015). Mediated mechanism of thriving at work between perceived organization support, innovative work behavior and turnover intention. Pakistan Journal of Commerce and Social Sciences, 9, 982-998. https://ssrn.com/abstract=2728112

Abid, G., Zahra, I., & Ahmed, A. (2016b). Promoting thriving at work and waning turnover intention: A relational perspective. Future Business Journal, 2(2), 127-137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fbj.2016.08.001

Alfredsson, L., Spetz, C. L., & Theorell, T. (1985). Type of occupation and near-future hospitalization for myocardial infarction and some other diagnoses. International Journal of Epidemiology, 14(3), 378-388. http://doi.org/10.1093/ije/14.3.378

Allenbaugh, G. E. (1983). Coaching... a management tool for a more effective work performance. Management Review, 72(5), 21-26.

Bakker, A. B., Tims, M., & Derks, D. (2012). Proactive personality and job performance: The role of job crafting and work engagement. Human Relations, 65(10), 1359-1378. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726712453471

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191.-215. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

Bandura, A. (1982). Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. American Psychologist, 37(2), 122.-147. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.37.2.122

Bar, S. G. (2014). How personal systems coaching increases selfefficacy and well-being for Israeli single mothers. International Journal of Evidence Based Coaching and Mentoring, 12(2), 59-74.

Baron, L., & Morin, L. (2010). The impact of executive coaching on self-efficacy related to management soft-skills. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 31(1), 18-38. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/01437731011010362

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173.-1182. http://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173

Beattie, R. S., Kim, S., Hagen, M. S., Egan, T. M., Ellinger, A. D., & Hamlin, R. G. (2014). Managerial coaching: A review of the empirical literature and development of a model to guide future practice. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 16(2), 184-201. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1523422313520476

Beehr, T. A., & Newman, J. E. (1978). Job stress, employee health, and organizational effectiveness: A facet analysis, model, and literature review. Personnel Psychology, 31(4), 665-699. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1978.tb02118.x

Borman, W. C., Penner, L. A., Allen, T. D., & Motowidlo, S. J. (2001). Personality predictors of citizenship performance. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 9(1‐2), 52-69. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2389.00163

Brown, D. J., Arnold, R., Fletcher, D., & Standage, M. (2017). Human thriving: A conceptual debate and literature review. European Psychologist. http://dx.doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000294

Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sage Focus Editions, 154, 136-136. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124192021002005

Bryl, Ł. (2018). Human capital orientation and financial performance: A comparative analysis of US corporations. Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Innovation, 14(3), 61-86. http://doi.org/10.7341/20181433

Cameron, K. (2012). Positive Leadership: Strategies for Extraordinary Performance. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Carmeli, A., & Spreitzer, G. M. (2009). Trust, connectivity, and thriving: Implications for innovative behaviors at work. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 43(3), 169-191. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2162-6057.2009.tb01313.x

Chen, G., Gully, S. M., & Eden, D. (2001). Validation of a new general self-efficacy scale. Organizational Research Methods, 4(1), 62-83. https://doi.org/10.1177/109442810141004

Crant, J. M., & Bateman, T. S. (2000). Charismatic leadership viewed from above: The impact of proactive personality. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 63-75. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1379(200002)21:1<63::AID-JOB8>3.0.CO;2-J

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). The general causality orientations scale: Self-determination in personality. Journal of Research in Personality, 19(2), 109-134. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0092-6566(85)90023-6

Dudley, N. M., & Cortina, J. M. (2008). Knowledge and skills that facilitate the personal support dimension of citizenship. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(6), 1249-1270. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0012572

Ehrenfeld, J. (2008). Sustainability by Design: A Subversive Strategy for Transforming our Consumer Culture. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press.

El Bedawy, R. (2015). A review for embedding human dimension of sustainability to maintain energetic organizations in Egypt. Journal of Management and Sustainability, 5(1), 158-167. http://doi.org/10.5539/jms.v5n1p158

Elahi, N. S., Abid, G., Arya, B., & Farooqi, S. (2019). Workplace behavioral antecedents of job performance: Mediating role of thriving. The Service Industries Journal, 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2019.1638369

Elkington, J. (1997). Cannibals with Forks. The Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century. New York: John Wiley & Son.

Ellinger, A.D., Ellinger, A.E., & Keller, S.B. (2003). Supervisory coaching behavior, employee satisfaction, and warehouse employee performance: A dyadic perspective in the distribution industry. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 14(4), 435-458. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrdq.1078

Elmadağ, A. B., Ellinger, A. E., & Franke, G. R. (2008). Antecedents and consequences of frontline service employee commitment to service quality. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 16(2), 95-110. https://doi.org/10.2753/MTP1069-6679160201

Evered, R. D., & Selman, J. C. (1989). Coaching and the art of management. Organizational Dynamics, 18(2), 16-32. https://doi.org/10.1016/0090-2616(89)90040-5

Fehr, R., & Gelfand, M. J. (2012). The forgiving organization: A multilevel model of forgiveness at work. Academy of Management Review, 37(4), 664-688. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23416291

Field, A.P. (2013). Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics: And sex and Drugs and Rock ‘N’ Roll (fourth edition). London: Sage Publications.

Flinchbaugh, C., Luth, M. T., & Li, P. (2015). A challenge or a hindrance? Understanding the effects of stressors and thriving on life satisfaction. International Journal of Stress Management, 22(4), 323. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0039136

Frazier, M. L., & Tupper, C. (2016). Supervisor prosocial motivation, employee thriving, and helping behavior: A trickle-down model of psychological safety. Group & Organization Management. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601116653911

Fritz, C., Lam, C. F., & Spreitzer, G. M. (2011). It’s the little things that matter: An examination of knowledge workers’ energy management. The Academy of Management Perspectives, 25(3), 28-39. http://doi.org/10.5465/AMP.2011.63886528

Galup, S. D., Klein, G., & Jiang, J. J. (2008). The impacts of job characteristics on IS employee satisfaction: A comparison between permanent and temporary employees. Journal of Computer Information Systems, 48(4), 58-68. http://doi.org/10.1080/08874417.2008.11646035

Gebauer, J. E., Riketta, M., Broemer, P., & Maio, G. R. (2008). Pleasure and pressure based prosocial motivation: Divergent relations to subjective well-being. Journal of Research in Personality, 42(2), 399-420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2007.07.002

Gerbasi, A., Porath, C. L., Parker, A., Spreitzer, G., & Cross, R. (2015). Destructive de-energizing relationships: How thriving buffers their effect on performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(5), 1423. http://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000015

Gilley, A., Gilley, J. W., & Kouider, E. (2010). Characteristics of managerial coaching. Performance Improvement Quarterly, 23(1), 53-70. https://doi.org/10.1002/piq.20075

Gist, M. E., & Mitchell, T. R. (1992). Self-efficacy: A theoretical analysis of its determinants and malleability. Academy of Management Review, 17(2), 183-211. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/258770

Grant, A. M. (2014). The efficacy of executive coaching in times of organisational change. Journal of Change Management, 14(2), 258-280. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14697017.2013.805159

Grant, A. M., & Berry, J. W. (2011). The necessity of others is the mother of invention: Intrinsic and prosocial motivations, perspective taking, and creativity. Academy of Management Journal, 54(1), 73-96. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.59215085

Grant, A. M., & Rothbard, N. P. (2013). When in doubt, seize the day? Security values, prosocial values, and proactivity under ambiguity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 98(5), 810-819. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0032873

Grant, A. M., & Sumanth, J. J. (2009). Mission possible? The performance of prosocially motivated employees depends on manager trustworthiness. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(4), 927-944. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0014391

Hagen, M. S. (2012). Managerial coaching: A review of the literature. Performance Improvement Quarterly, 24(4), 17-39. https://doi.org/10.1002/piq.20123

Hall, R. J., Snell, A. F., & Foust, M. S. (1999). Item parceling strategies in SEM: Investigating the subtle effects of unmodeled secondary constructs. Organizational Research Methods, 2(3), 233-256. https://doi.org/10.1177/109442819923002

Hamlin, R. G., Ellinger, A. D., & Beattie, R. S. (2006). Coaching at the heart of managerial effectiveness: A cross-cultural study of managerial behaviours. Human Resource Development International, 9(3), 305-331. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13678860600893524

Hayes, A. F. (2012). PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling. Retrieved from http://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf

Hoffman, A.J.; Haigh, N. (2011). Positive deviance for a sustainable world: Linking sustainability and positive organizational scholarship. In K. Cameron & G. Spreitzer (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Positive Organizational Scholarship (pp. 953-964). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Hooper, D., Coughlan, J., & Mullen, M. R. (2008). Structural equation modelling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Journal of Business Research Methods, 6(1), 53–60. http://www.ejbrm.com/vol6/v6-i1/v6-i1-papers.htm

Hoyle, R. H. (1995). Structural Equation Modeling: Concepts, Issues, and Applications. London: Sage.

Hu, J., & Liden, R. (2015). Making the difference in the teamwork: Linking team proscocial motivation to team processes and effectiviness. Academy of Management Journal, 58(4), 1102–1127. http://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2012.1142

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: a Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1-55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Jiang, Z. (2017). Proactive personality and career adaptability: The role of thriving at work. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 98, 85-97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2016.10.003

Judge, T. A., & Bono, J. E. (2001). Relationship of core self-evaluations traits—self-esteem, generalized self-efficacy, locus of control, and emotional stability—with job satisfaction and job performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 80. http://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.1.80

Kim, S., Egan, T. M., & Moon, M. J. (2014). Managerial coaching efficacy, work-related attitudes, and performance in public organizations: A comparative international study. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 34(3), 237-262. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734371X13491120

Kira, M., & van Eijnatten, F. M. (2008). Human and Social Sustainability in Work Organizations. Proposal International Research Program SUSTAIN. Espoo/ Eindhoven: Helsinki University of Technology, Department of Industrial Engineering/ Eindhoven University of Technology, Department of Technology Management.

Kleine, A. K., Rudolph, C. W., & Zacher, H. (2019). Thriving at work: A meta analysis. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 40(9-10), 973-999. http://doi.org/10.1002/job.2375.

Lee, S. H., & Ha-Brookshire, J. (2017). Ethical climate and job attitude in fashion retail employees’ turnover intention, and perceived organizational sustainability performance: A cross-sectional study. Sustainability, 9(3), 465-475. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9030465

Levene, R. A. (2015). Positive psychology at work: Psychological capital and thriving as pathways to employee engagement. Retrieved from http://repository.upenn.edu/mapp_capstone/88

Little, T. D., Cunningham, W. A., Shahar, G., & Widaman, K. F. (2002). To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the question, weighing the merits. Structural Equation Modeling, 9(2), 151-173. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_1

Liu, W., Steve Chi, S. C., Friedman, R., & Tsai, M. H. (2009). Explaining incivility in the workplace: The effects of personality and culture. Negotiation and Conflict Management Research, 2(2), 164-184. https://ink.library.smu.edu.sg/soss_research/2048

Liu, X., & Batt, R. (2010). How supervisors influence performance: A multilevel study of coaching and group management in technology‐mediated services. Personnel Psychology, 63(2), 265-298. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2010.01170.x

Marsh, H. W., Balla, J. R., & Hau, K. T. (1996). An evaluation of incremental fit indices: A clarification of mathematical and empirical properties. In G. A. Marcoulides, & R. E. Schumacker (Eds.), Advanced Structural Equation Modeling Techniques (pp. 315-353). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Maslow, A. H. (1954). The instinctive nature of basic needs. Journal of Personality, 22(3), 326-347. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1954.tb01136.x

Moen, F., & Allgood, E. (2009). Coaching and the effect on self-efficacy. Organization Development Journal, 27(4), 69-82.

Mushtaq, M., Abid, G., Sarwar, K., Ahmed, S. (2017). Forging ahead: How to thrive at the modern workplace. Iranian Journal of Management Studies, 10(4), 783-818. http://doi.org/10.22059/IJMS.2017.235409.672704

Nawaz, M., Abid, G., Arya, B., Bhatti, G. A., & Farooqi, S. (2018). Understanding employee thriving: The role of workplace context, personality and individual resources. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence. http://doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2018.1482209

Niessen, C., Sonnentag, S., & Sach, F. (2012). Thriving at work—A diary study. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33(4), 468-487. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.763

O’Leary, V. E., & Ickovics, J. R. (1995). Resilience and thriving in response to challenge: An opportunity for a paradigm shift in women’s health. Women’s Health, 1(2), 121-142.

Organ, D. W., & Ryan, K. (1995). A meta‐analytic review of attitudinal and dispositional predictors of organizational citizenship behavior. Personnel Psychology, 48(4), 775-802. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1995.tb01781.x

Parker, P., Kram, K. E., & Hill, D. T. T. (2014). Peer coaching: An untapped resource for development. Organizational Dynamics, 43(2), 122-129. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2014.03.006

Paterson, T. A., Luthans, F., & Jeung, W. (2014). Thriving at work: Impact of psychological capital and supervisor support. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 35(3), 434-446. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1907

Pereverzieva, A. (2019). A methodical approach to the assessment of human resources interactions. Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Innovation, 15(1), 171-204. https://doi.org/10.7341/20191517

Pfeffer, J. (2010). Building sustainable organizations: The human factor. The Academy of Management Perspectives, 24(1), 34-45. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.24.1.34

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63, 539-569. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452

Porath, C., Spreitzer, G., Gibson, C., & Garnett, F. G. (2012). Thriving at work: Toward its measurement, construct validation, and theoretical refinement. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33(2), 250-275. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.756

Pousa, C., & Mathieu, A. (2015). Is managerial coaching a source of competitive advantage? Promoting employee self-regulation through coaching. Coaching: An International Journal of Theory, Research and Practice, 8(1), 20-35. https://doi.org/10.1080/17521882.2015.1009134

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879-891. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.40.3.879

Purvanova, R. K., & Muros, J. P. (2010). Gender differences in burnout: A meta-analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 77(2), 168-185. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2010.04.006

Qaiser, S., Abid, G., Arya, B., & Farooqi, S. (2018). Nourishing the bliss: Antecedents and mechanism of happiness at work. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence. http://doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2018.1493919

Ren, H., Yunlu, D. G., Shaffer, M., & Fodchuk, K. M. (2015). Expatriate success and thriving: The influence of job deprivation and emotional stability. Journal of World Business, 50(1), 69-78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2014.01.007

Rioux, S. M., & Penner, L. A. (2001). The causes of organizational citizenship behavior: A motivational analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(6), 1306-1314. http://doi.org/ 10.1037/0021-9010.86.6.1306

Shan, S. (2016). Thriving at workplace: Contributing to self-development, career development, and better performance in information organizations. Pakistan Journal of Information Management & Libraries, 17, 109-119.

Shirom, A. (2004). Feeling vigorous at work? The construct of vigor and the study of positive affect in organizations. In P. L. Perrewé & D. C. Ganster (Eds.), Research in Occupational Stress and Well-Being: Vol. 3. Emotional and Physiological Processes and Positive Intervention Strategies (pp. 135–164). Elsevier Science/JAI Press.

Spreitzer, G. (2008). Toward the integration of two perspectives: A review of social-structural and psychological empowerment at work. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Gretchen_Spreitzer/publication/228915522_Toward_the_integration_of_two_perspectives_A_review_of_social-structural_and_psychological_empowerment_at_work/links/54b8f8b70cf269d8cbf72818/Toward-the-integration-of-two-perspectives-A-review-of-social-structural-and-psychological-empowerment-at-work.pdf

Spreitzer, G. M., Lam, C. F., & Fritz, C. (2010). Engagement and human thriving: Complementary perspectives on energy and connections to work. In A. B. Bakker & M. P. Leiter (Eds.), Work Engagement: A Handbook of Essential Theory and Research (pp. 132-146). Rotterdam: Erasmus University Rotterdam.

Spreitzer, G., Porath, C. L., & Gibson, C. B. (2012). Toward human sustainability: How to enable more thriving at work. Organizational Dynamics, 41(2), 155-162. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2012.01.009

Spreitzer, G., Sutcliffe, K., Dutton, J., Sonenshein, S., & Grant, A. M. (2005). A socially embedded model of thriving at work. Organization Science, 16(5), 537-549. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1050.0153

Stajkovic, A. D., & Luthans, F. (1998). Self-efficacy and work-related performance: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 124(2), 240-261. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.124.2.240

Uchino, B. N., Berg, C. A., Smith, T. W., Pearce, G., & Skinner, M. (2006). Age-related differences in ambulatory blood pressure during daily stress: Evidence for greater blood pressure reactivity with age. Psychology and Aging, 21(2), 231-239. http://doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.21.2.231

Wallace, J. C., Butts, M. M., Johnson, P. D., Stevens, F. G., & Smith, M. B. (2016). A multilevel model of employee innovation: Understanding the effects of regulatory focus, thriving, and employee involvement climate. Journal of Management, 42(4), 982-1004. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206313506462

Walumbwa, F. O., Muchiri, M. K., Misati, E., Wu, C., & Meiliani, M. (2017). Inspired to perform: A multilevel investigation of antecedents and consequences of thriving at work. Journal of Organizational Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2216

Wood, R., & Bandura, A. (1989). Impact of conceptions of ability on self-regulatory mechanisms and complex decision making. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56(3), 407-415. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.56.3.407

Zhang, J., Jensen, B. E., & Mann, B. L. (1997). Modification and revision of the leadership scale for sport. Journal of Sport Behavior, 20(1), 105-122.

Zhu, Y., & Akhtar, S. (2014). How transformational leadership influences follower helping behavior: The role of trust and prosocial motivation. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 35(3), 373-392. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1884

Zieba, K. & Golik, J. (2018). Testing students’ entrepreneurial self-efficacy as an early predictor of entrepreneurial activities. Evidence from the SEAS project. Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Innovation, 14(1), 91-10. http://doi.org/10.7341/20181415

Other sources

Forbes (2013). The causes and costs of absenteeism in the workplace. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/investopedia/2013/07/10/the‐causes‐and‐costs‐of‐absenteeism‐in‐the‐workplace/#4ffa949b3eb6

Gallup (2013). In U.S., poor health tied to big losses for all job types. Retrieved from http://www.gallup.com/poll/162344/poor‐health‐tied‐big‐losses‐job‐types.aspx

Merriam-Webster Dictionary (2019). Retrieved from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/thrive

Abstrakt

Stan psychiczny, w którym jednostka doświadcza formy witalności i poczucia uczenia się w pracy, jest znany jako dobrze prosperujący w pracy. Od nowego tysiąclecia badania empiryczne pokazują, że dobrze prosperujący (zrównoważony rozwój pracowników) ma kluczowe znaczenie dla stabilności organizacyjnej. Jednak ten ludzki wymiar zrównoważonego rozwoju jest zaniżony i niewiele wiadomo na temat tego, w jaki sposób indywidualne cechy i kierownicy promują dobrze prosperujących pracowników w pracy. Aby wypełnić tę lukę, to pionierskie badanie bada kontekst pracy i różnice indywidualne w promowaniu dobrze prosperującego miejsca pracy. Interwencyjny mechanizm własnej skuteczności i motywacji prospołecznej między coachingiem menedżerskim a dobrze prosperującym w pracy został zbadany przy użyciu sekwencyjnego podejścia mediacyjnego. Dane zostały przeanalizowane przy użyciu modelu 6 w procesie Hayesa (opartego na ponownym próbkowaniu 1000 ładowań początkowych) z rzeczywistą próbą 221 respondentów. Nasze wyniki wspierają nasz hipotetyczny model. Badanie wykazuje bezpośredni związek między coachingiem menedżerskim a poczuciem własnej skuteczności. Stwierdza się, że poczucie własnej skuteczności jest bezpośrednio związane z motywacją prospołeczną, a tym samym poprawia rozwój pracownika w pracy. Stwierdzono również, że skuteczność i motywacja prospołeczna odgrywają istotną rolę w wyjaśnianiu związku między coachingiem menedżerskim a dobrze prosperującym miejscem pracy.

Słowa kluczowe: coaching menedżerski, skuteczność własna, motywacja prospołeczna, dobrze prosperujący w pracy, sekwencyjna mediacja

Biographical notes

Ghulam Abid is an assistant professor of Management in School of Business Administration at National College of Business Administration & Economics (NCBA&E), Lahore, Pakistan. He received his Ph.D. degree from the NCBA&E. His research focuses on employee thriving and positive organizational scholarship. His most recent research is on examining how organizations can create a more positive environment where individuals can thrive; and how organizations benefit in terms of positive behavioral outcomes. He is among one of the too few authors in the world who are working on these emerging issues of the 21st century. He has made a remarkable contribution to novel literature through Impact Factor, ISI and Scopus indexed journals in addition to national/international conferences. In the domain of data analysis, he has proven himself an expert in the field by conducting numerous workshops, training sessions, and playing the role of session chair in many prestigious international conferences.

Saira Ahmed received her Bachelor of Science in Business Studies Degree from University of Lancaster, the UK, with first-class honors and was awarded Chancellor’s Medal in 2016, and also Bachelors of Science in Business Administration from COMSATS University Lahore, Pakistan. She has a Master in Business Administration from University of Engineering and Technology, Lahore, Pakistan. Her recent research work involved human resource development, e-government with positive organizational scholarship. Her area of interest covers investigation about human aspect involvement for digitization of organizational processes and related behavioral development of the workforce.

Tehmina Fiaz Qazi is currently serving as assistant professor at Institute of Business & Management, University of Engineering & Technology, Lahore, Pakistan. She obtained her Ph.D. degree in Business Administration from Pakistan. Her research work includes several research papers published in recognized international and national journals and conferences. Her areas of interest include organizational behavior, consumer behavior, strategic management, leadership, and human resource management.

Komal Sarwar has completed her Masters in Business Administration from NCBA&E Lahore, Pakistan. Her area of interest involves human resource management and the practical implications of theoretical concepts of organizational behavior in emerging organizations.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Citation (APA Style)

Abid, G., Ahmed, S., Fiaz Qazi, T., & Sarwar, K. (2020). How managerial coaching enables thriving at work. A sequential mediation. Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Innovation, 16(2), 131-160. https://doi.org/10.7341/20201625