Received 31 August 2018; Revised 31 December 2018; Accepted 10 February 2019

Rose Quan, D.B.A., Northumbria University, Ellison Road, Ellison Building, Newcastle upon Tyne, the UK, NE1 8ST, e-mail: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Mingyue Fan, Ph.D., Jiangsu University, No. 301, Xuefu Road, Zhenjiang, Jiangsu, China, 212013, e-mail: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. (corresponding author)

Michael Zhang, Ph.D., Nottingham Trent University, 50 Shakespeare St, Nottingham, the UK, NG1 4FQ, e-mail: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Huan Sun, Northumbria University, Ellison Road, Ellison Building, Newcastle upon Tyne, the UK, NE1 8ST, e-mail: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Abstract

Effective embeddedness in the host country is an important issue for immigrant and transnational entrepreneurs. However, prior research has mainly focused on subsidiaries’ local embeddedness of multinational companies (MNCs). While a limited number of studies have examined transnational enterprises, few have explored how transnational entrepreneurs embed in the host country where they immigrate to. Employing 7 in-depth case studies of Chinese small transnational enterprises operating in the UK, we construct a dynamic dual process model which consists of 3 dimensions: structural embeddedness; institutional embeddedness; and cognitive embeddedness. Our findings make a theoretical contribution by offering insights into how transnational migrant entrepreneurs embed in a dual cross-border business environment.

Keywords: Transnational entrepreneurship, host country, institutional theory, embeddedness

INTRODUCTION

Transnational immigrant entrepreneurship has received increasing research attentions in recent times (Bagwell, 2015; Brzozowski, Cucculelli, & Surdej, 2017; Elo et al., 2018). It has been found that transnational immigrant entrepreneurs make a great contribution to the local economy by generating jobs and forming valuable social hubs. According to Johnson and Kimmelman (2014), 60% of the top technology businesses were started by ‘migrants’ in the US. As ‘a new horizon, in entrepreneurship and international business studies’ (Sequeira, Carr & Rasheed, 2009, p.31), research in transnational entrepreneurship (TE) literature highlights that transnational entrepreneurs face more difficulties and challenges when operating in a dual business context (Bagwell, 2018; Chen & Tan, 2009). TEs are those who immigrate to a foreign country, but do not limit their business activities to the host country only (Dimitratos, Buck, Fletcher, & Li, 2016; Urbano, Toledano, & Ribeiro-Soriano, 2011), simultaneously engaging in two or more socially embedded environment (Drori, Honig, & Wright, 2009).

Embeddedness is a topic often discussed in economic transnationalism research (Sequeira, Carr, & Rasheed, 2009). Individuals or groups engaged in economic transnationalism utilize their social sources, such as interfirm networks (Granovetter, 1985), to facilitate economic actions and shape organizational outcomes (Uzzi, 1997). Given the fact that local embeddedness in the host country affects firms’ overall performance, international entrepreneurship researchers (McDougall & Oviatt, 2000; Zahra & George, 2002) and ethnic entrepreneurship researchers (Rath & Kloosterman, 2000; Yinger, 1985) have extensively examined entrepreneurial cross-nation activities in the areas of (1) opportunity seeking and value creation in the host country (McDougall & Oviatt, 2000); (2) born global firms (Mainela, Puhakka, & Servais, 2014); (3) knowledge transfer of returning entrepreneurship in home country (Kenney, Breznitz, & Murphree, 2013; Liu, Lu, Filatotchev, Buck, & Wright, 2010; Pruthi, 2014).

With an increasing number of migrant entrepreneurs attempting to embed in the host country, it has become important for TE researchers to understand their ‘embeddedness’ and extend the development of transnational immigrant entrepreneurship. By reviewing existing international entrepreneurship literature, nevertheless, very few studies have explored the embeddedness of transnational immigrant entrepreneurship (Bagwell, 2018). To fill this research gap, our paper aims to explore: How do transnational immigrant entrepreneurs embed in the host country successfully, especially in the UK? What is the process of the embeddedness for small transnational enterprises? Answers to these questions enhance TE researchers’ understanding of this phenomenon by providing empirical evidence in the context of Chinese transnational entrepreneurs in the UK. The reason for making this case is because migrant-founded enterprises in the UK employ 1.16 million people and contribute to 14% of SME job-creation (Johnson & Kimmelman, 2014). Amongst these migrant entrepreneurs, about 25,000 have a Chinese background (Dimitratos, Buck, Fletcher, & Li, 2016). However, to our best knowledge, there is only one study (Dimitratos, Buck, Fletcher, & Li, 2016) that investigated the motivation of Chinese transnational entrepreneurs in the UK. We extend their research by investigating the embeddedness in the host country.

Given the nature of the ‘how’ design for this research, we conducted 7 in-depth case studies by sampling Chinese small entrepreneurial enterprises operating in the UK. Due to the fact that the TE phenomenon is still in its emerging stage (Urbano, Toledano, & Ribeiro-Soriano, 2011), case studies will allow us to discover the theoretical inside through inductive inquiry (Eisenhardt, 1989; Yin, 2003). Our findings show that the transnational enterprises’ embeddedness is a dynamic and interactive three-stage process (e.g., structure embeddedness, institutional embeddedness and cognitive embeddedness) which involves both host country and home country. Our research makes a theoretical contribution to immigrant and transnational entrepreneurship literature by offering insight into how small transnational enterprises embed their businesses in the host country, especially in the UK. Conceptually, it offers knowledge of Chinese transnational immigrant entrepreneurs’ dual transnational activities. In practice, this paper presents empirical evidence for immigrant policymakers to consider how to continuously support transnational immigrant entrepreneurs to achieve long-time growth, particularly given the fact that one in seven of all UK companies is run by migrant entrepreneurs in the UK (Johnson & Kimmelman, 2014).

Following this introduction, the structure of this article is as follows. First, the theoretical background of transnational entrepreneurship and embeddedness is presented as an overview of the literature. This is followed by a detailed account of the methods we adopted for this research along with our findings and discussions. Finally, the conclusions are presented with suggestions for future research.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Definition of transnational entrepreneurship

Empirical evidence has shown that globalization has facilitated even the small immigrant-created businesses into a transnational realm (Light, 2007). As a newly emerged phenomenon, research on TE has attracted growing attention in ethnic entrepreneurship studies (Elo et al., 2018; McGrath & O’Toole, 2014). The research on TE first appeared in the middle of the 1990s when Basch, Schiller and Blanc (1994) defined TE as the process by which immigrants forge and sustain multi-stranded social relations that link together their societies of origin and settlement, and through which they create transnational social fields across national borders. Similarly, Drori, Honig and Wright (2009) define transnational entrepreneurs as ‘individuals that migrate from one country to another, concurrently maintaining business-related linkages with their forms country of origin, and currently adopted communities (p. 1001)’. These concepts provide a new view of the greater intensity and extent of circulation of people, goods, information and symbols caused by immigration (Ley, 2006; Pavlov, Predojević-Despić, & Milutinović, 2013; Riddle, Hrivnak, & Nielsen, 2010). Economic geographers and regional planners view the role of TEs as influencing the creation of business opportunities and affecting the transfer of knowledge, technology and know-how. They are regarded as a catalyst for the evolution of global production networks (Mustafa & Chen, 2010; Saxenian, 2002).

Embeddedness and networks

As a concept of transnationalism, ‘embeddedness’ was first introduced by Polanyi (1944) and is used to understand how social structure affects economic activities (as cited in Uzzi, 1997). Embeddedness reflects the degree to which firms are enmeshed in a social network in different situations (Uzzi, 1997). Many studies in relation to embeddedness have overwhelmingly examined MNCs’ cross-board activities in the host country by focusing on: (1) the relationship between a subsidiary and its local counterparts in the host country (external embeddedness) (Granovetter, 1985; Meyer & Nguyen, 2005); (2) a subsidiary’s relationship with its parent MNCs (internal embeddedness) (Andersson & Forsgren, 1996; Nell, Ambos, & Schlegelmilch, 2011); (3) the combination of internal embeddedness and external embeddedness (Andersson, Björkman, & Forsgren, 2005; Forsgren, Holm, & Johanson, 1992). However, given the liabilities of small and newness, it is rational to assume that the embeddedness of small entrepreneurial enterprises, compared to MNCs’ subsidiaries, is more difficult and complex. Nevertheless, not much has been explored and theorized well in this research area (McKeever, Jack, & Anderson, 2015).

Entrepreneurship is a socialized process and entrepreneurs are social actors. Entrepreneurial business activities are inevitably integrated into the community (Chen & Tan, 2009; Davidsson & Honig, 2003; Riddle, Hrivnak, & Nielsen, 2010). Social networks have considerable effects on a wide range of organizational performance. From a social network perspective, embeddedness in the context of entrepreneurship reflects ‘the relationship between entrepreneurship, self and society’ (McKeever, Jack, & Anderson, 2015, p. 52). Existing literature indicates that entrepreneurial embeddedness is a mechanism which influences and shapes entrepreneurs’ actions (Jack & Anderson, 2002; Uzzi, 1997). In order to better survive in the foreign markets, migrant entrepreneurs attempt to develop a variety of ties in local society at multi-levels (e.g., individual, groups and societies), through which they identify opportunities and absorb social capital to overcome the liability of smallness and newness. By accessing local social resources, entrepreneurs quickly accumulate institutional knowledge of the host country and create added value to their foreign businesses (Welter, 2011). According to Mainela and Puhakka (2008), densely tied local networks and high-quality relational embeddedness are benefits that help firms develop dynamic and valuable capabilities.

The research into transnational entrepreneurship shows that they access resources across borders in order to make use of their contacts and networks by engaging in social and business activities in both countries (Mustafa & Chen, 2010). Successful embeddedness in the host country has been a key indicator in explaining the success of migrant entrepreneurs. Their social and economic embeddedness determines entrepreneurial outcomes. According to Bagwell (2018), not only transnational networks play a key role in shaping the embeddedness of Vietnamese migrant enterprises in London, but the macro level of institutional characteristics also has an impact of transnational enterprises’ embeddedness.

Institutional embeddedness and entrepreneurial behaviors

North (1990, p. 3) claims that institutions form ‘the rules of the game in a society.’ Institution-based theory suggests that institutions, both formal and informal, constrain or enable business strategies, such as internationalization decisions (Meyer & Peng, 2005). Formal rules include constitutions and legal regulations, and informal institutions refer to codes of conduct, values and norms (soft institutions) embedded in society (Scott, 1995). According to Peng and Heath (1996), the behavioral characteristics of enterprises are heavily influenced by the external environment. As social actors, entrepreneurs’ behaviors are constrained, enabled and shaped by the institutional frame (Yamakawa, Peng, & Deeds, 2008).

Transnational entrepreneurs take an unusual route to organize and produce their economic activities and their actions are ‘facilitated and constrained by an ongoing process of institutional relations in both home and host countries’ (Yeung, 2002, p. 30). The embedded structures of institutional relations shape transnational enterprises’ outcomes of economic activities across borders. As the institutional environment in their home country is substantially different in many aspects compared to their host country, particularly in the context of firms from developing markets entering the developed countries, transnational entrepreneurs are eager to develop dual capabilities in both host and home countries in order to better understand multiple institutional environments (Drori, Honig, & Wright, 2009), and better exercise their home country endowments in the host country in the institutional context (Bagwell, 2015; Yeung, 2002). There are different levels of institutions, such as government policies and industrial policies. These elements, in accordance with business functions (e.g., resource control, leverage capabilities and exploit opportunities), create great challenges for transnational entrepreneurs to firmly embed their business in the host country (Urbano, Toledano, & Ribeiro-Soriano, 2011).

Given the fact that country-specific entrepreneurial factors have an impact on transnational migrant enterprises’ performance (Bagwell, 2018; Brzozowski, Cucculelli, & Surdej, 2014), TE researchers have investigated transnational migrant entrepreneurs from different nations in both emerging (Riddle, Hrivnak, & Nielsen, 2010) and developed countries (Bagwell, 2018). Reviewing the existing TE literature, we found that a limited number of studies examine Chinese transnational entrepreneurship in general. The current Chinese-related TE studies mainly focus on motivation (Urbano, Toledano, & Ribeiro-Soriano, 2011), opportunity seeking (Lin & Tao, 2012) and value creation (Lan & Zhu, 2014; Wong & Ng, 2002).

Bagwell (2018) in her study investigated the embeddedness of Vietnamese transnational business activities in London and highlighted the importance of successful embeddedness of transnational entrepreneurs in the host country. Nevertheless, none of the studies has specifically explored the ‘embeddedness’ of Chinese transnational migrant entrepreneurship in the UK. As indicated in the Introduction section, an impressive 14% of SME job-creation is created by migrant entrepreneurs in the UK, and about 25,000 entrepreneurs have a Chinese background (Dimitratos, Buck, Fletcher, & Li, 2016; Johnson & Kimmelman, 2014). Discovering how these Chinese transnational migrant entrepreneurs successfully embed in the UK will extend the TE theory in a different context.

To construct our theoretical framework, we apply Nahapiet and Ghoshal’s (1998) social capital and intellectual capital framework, which comprises three dimensions: structural dimension (network ties and network configuration); cognitive dimension (knowledge of shared codes, language and culture); and relational dimension (trust and expectation).

RESEARCH METHODS

This study employs an exploratory multiple-case approach which has long been recognized as an efficient approach to examine a complex and under-explored phenomenon in a real-life context (Lee, 1999; Yin, 2003). Compared to a single case study, ‘multiple cases are generally regarded as more robust’ (Urbano, Toledano, & Ribeiro-Soriano, 2011, p. 123) as the multiple-case design enables cross-case checking for replication logic (Eisenhardt & Graebner, 2007). Qualitative case studies have been increasingly used in entrepreneurship research (Katila & Wahlbeck, 2012; Perren & Ram, 2004; Sabah, Carsrud, & Kocak, 2014). The qualitative case study approach offers a valuable opportunity to explore new insights and build new theoretical explanations for the observed phenomenon (Bruton, Khavul, & Chavez, 2011).

Our research aims to discover the process of ‘embeddedness’ of Chinese transnational enterprises in the UK; it is still an emerging and under-explored phenomenon in the TE research domain. To explore the insights of a relatively new phenomenon, multiple case studies are the most suitable research method and has been utilized by many TE researchers in the previous studies (Bagwell, 2018; Lan & Zhu, 2014; Urbano, Toledano, & Ribeiro-Soriano, 2011). Especially, Mustafa and Chen (2010) claimed that a multiple case method is particularly helpful in tracking process over time and explains why this method was employed for this study.

Data collection

Using a purposive sampling method (Pratt, 2009), we conducted 7 in-depth case studies. Two main control criteria are used in the case choices. First, all selected cases must be small Chinese enterprises, operating in the North of England (including North East and North West). Second, we choose cases that are as diverse as possible (Eisenhardt, 1989) to maximize the exploration of potential insights into the new phenomenon of transnational enterprises’ embeddedness in the host country. Following these selection criteria, the final 7 selected small Chinese entrepreneurial enterprises include: a hotel business (case 1); an online beauty products company (case 2); a property agency (the case 3); a Post Office (case 4); a combined Post Office and nail business (case 5); an electronic goods and bicycle retailer (case 6); and a pub business (case 7). Table 1 below describes the case backgrounds and the participants’ information.

Given the fact that a qualitative research approach provides creative ways to make a rich contribution (Bryman, 2003), we employed different data collection techniques through three stages from the qualitative perspectives. First, one of the researchers already had connections with the owners of these Chinese enterprises through a variety of ethnic, social events either in the UK or China. Taking advantage of this, several informal conversations, site-visits and observations were carried out in the first stage. Second, 8 in-depth semi-structured interviews were conducted.

Table 1. Summary of the cases

|

Firms |

Owners’ educational background |

Age of owners |

Years in business |

Years in cross-border business |

Types of cross- border business |

Funding resources |

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 |

PhD in Bus Mag PhD in e-business Master in Bus Mag Mater in Bus Mag PhD in computing Bachelor in Bus Mag Master |

36 40 35 33 45 33 55 |

8 10 11 6 10 12 4 |

3 10 4 5 4 10 2 |

Hotel Beauty products Property Agent Post office Post office + nail Electronic + bicycle English Pub |

Family/self Family/self Family Family Family Family Self |

The participants for the semi-structured interviews were either owner-managers or senior managers in the transnational enterprise. They were chosen as key informants because they had been heavily involved in their transnational businesses as front-line management and employees in both home and host countries. Their transnational experiences provided valuable insights in helping us to collect rich qualitative data. The authors used their personal networks in the UK, and either directly or indirectly contacted the key informants via email and WeChat (the Chinese version of WhatsApp), initially to gain access to the case companies, and then interview dates were arranged in later conversations. The main interview questions included 1) general questions to collect basic data on the firms; 2) transnational activities and social capital/ethnic links used to support these TE activities; 3) broad open-questions to ensure that the key points were covered.

Considering the participants were more comfortable in expressing their opinions using their native tongue (Wang et al., 2014), each interview was conducted in Mandarin Chinese and lasted for 1 hour on average. An interview protocol designed by the researchers collectively was utilized for the semi-structured interviews. 7 interviews were recorded with the permission of the interviewees. Following ethical principles of protecting research participants from harm and privacy (Fontana & Frey, 2004), the organizations and participants’ real names, as agreed prior to the formal interview, are replaced by fictional names. As the last stage, 3 post interviews were conducted to clarify ambiguities in the information collected in the first round of interviews.

Data analysis

The case analysis involved a three-step process by applying Yin’s (2003) case analysis method combined with Miles and Huberman’s (1994) data deduction and coding approach. As a first step, all interview transcripts were stored as word-process documents, and the researchers read the transcripts independently and repeatedly to get rid of the non- and less relevant raw materials. Second, using the protocols of an interview, combined with the research questions, an individual researcher carefully and manually coded the ‘emerged patterns’ for each individual case and left them as an open-coded database. The identified themes and patterns were coded in English. Some core quotes were selected and highlighted in the original transcripts. This process was repeatedly applied to each individual case until no new patterns emerged from all interview transcripts. The researchers compared their codes through numerous face-to-face meetings, emails and WeChat communications between the UK and China. Thirdly, the similarities and differences of the coded categories cross cases are compared and analyzed by using a constant comparative method inductively (McKeever, Jack & Anderson, 2015). In doing so, we developed the final coded categories to ensure the completed ‘code book’ ‘conveying the connections between the analyzed data and the emergent theory’ (Bansal & Corley, 2011, p. 512).

Evaluation of the research

Qualitative research has long been criticized for lacking structure, and being too subjective and difficult to replicate (Bryman, 2003). Qualitative researchers must build up confidence in the truth of the findings and convince researchers themselves and audiences that their findings are ‘worth taking account of’ (Lincoln & Guba, 1985, p.290). To hit its methodological merits and rigor, the researched cases and interviewees were carefully selected before the main research was conducted. The interviewed owner-managers are all Chinese, but many of them have been studying and living in the UK for more than 10 years. Their in-depth understanding of both Chinese and British culture enables them to provide the most valuable information, which enhanced the quality of this study. In addition, all research files, such as interview transcripts, fieldwork notes, and discussions notes have been maintained in an accessible manner to achieve ‘dependability.’ Finally, during the whole data analysis process, 1-2 regular meetings were organized between the researchers every week at the early stages to discuss and confirm the emerged patterns. This step is very important to maintain a high degree of consistency.

ANALYSIS AND RESULTS

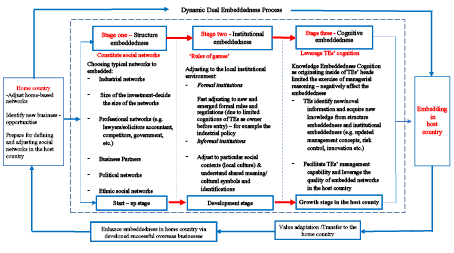

Our findings show that three embeddedness forms in the host country emerged at different stages after these small Chinese enterprises started up their businesses in the UK. Based on the inductive model, we identified a hierarchical process of embeddedness: (1) structure embeddedness in the start-up stage; (2) institutional embeddedness in the early development stage; and (3) cognitive embeddedness in the growth stage (see Table 2).

Table 2. Three types of embeddedness at different stages

|

Lifecycle stage |

Start-up stage |

Development stage |

Growth stage |

|

Embeddedness types |

Structure embeddedness (SE) |

Institution embeddedness (IE) |

Cognitive embeddedness (CE) |

|

|

|

|

In addition, we found that the identified hierarchical embeddedness is an ongoing and interactive process in a dual environment. Successfully embedding in the host country is affected by network forces in the firms’ home country. While enterprises accumulate novel information and knowledge of the foreign markets and improve their business performance in the host country, advice gained from the support network in their home country also contributed to deeper embeddedness in their host country.

Stage one: Structure embeddedness

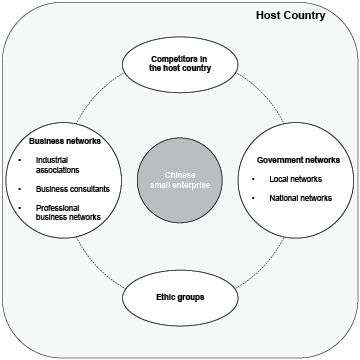

As shown in Figure 1, the invested small Chinese enterprises attempted to structure and embed themselves into 4 social groups in the host countries at the start-up stage, including (1) business networks; (2) ethnic groups; (3) Government networks; and (4) competitors in the host country (UK).

Figure 1. The chosen networks are structured by Chinese small enterprises in UK

The evidence from the 7 case studies shows that once small Chinese enterprises started their businesses in the UK, each firm invested affordable time and resources (due to the liability of smallness) to choose different networks to embed with in the host country. The evidence summarized in Table 3 shows a variety of networks choices at the earlier stage.

Amongst the 4 types of networks, professional networks (e.g., web-designers; accountants, solicitors, business managers of banks, etc.) and Chinese ethnic networks (e.g., Chinese North East Association and Chinese SMEs Association in the UK, etc.) were highlighted by all interviewees. Dealing with accountants, solicitors and business account bank managers were the first inevitable ‘networks to embed’ for all firms after they entered the UK.

Table 3. Summary of the network embeddedness

|

Network embeddedness |

C1 |

C2 |

C3 |

C4 |

C5 |

C6 |

C7 |

(%) |

|

|

Business networks |

Industrial associations |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

43 |

||||

|

Business consultants |

✓ |

✓ |

29 |

||||||

|

Professional business networks |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

100 |

|

|

Ethic groups |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

100 |

|

|

Government networks |

Local networks |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

71 |

||

|

National networks |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

43 |

|||||

|

Competitors in the host country |

✓ |

14 |

|||||||

|

In total |

5 |

4 |

3 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

||

Meanwhile, embedding into Chinese ethnic groups in the host country was also highlighted by all interviewees, as the following quotes demonstrate:

‘As a Chinese entrepreneur, the Chinese cultural features won’t diminish with the passage of the time and changes of location. Wherever and whenever, it affects your behaviors. Getting to know local Chinese individuals and institutions is the first step if you want to embed your business in the host country successfully as they have more experience, you can learn from them’ (case 2)

‘I received lots of advice and support from him (the Chinese owner-manager in case 4), he started the post office business a few years early than me, and his experiences of failure and success are all treasure for me. We meet regularly’ (case 5)

Owner-managers from five enterprises (cases 1, 3, 5-7) out of 7 (71%) claimed that they attempted to establish a good relationship with local government to receive professional supports for free and utilize their powerful influence. This perception might be due to the high power distance and ‘Guanxi’ culture in Chinese business practices, as the majority of interviewed Chinese entrepreneurs highlighted that a good relationship with government is crucial, as an interviewee explained: ‘this relationship (with Government) benefits our business not just now but in the future’. In addition, three interviewees (cases 2, 4 and 6) out of 7 (42%) admitted that apart from local government, they participated in numerous activities and meetings organized by One North East, a business support agent controlled by UK central government at the national level.

In addition, two enterprises (cases 4 and 5) out of 7 (29%) made links with local Industrial Associations, others (cases 1 and 2, 29%) built a network relationship with private business consultant companies. Interviewees from cases 4 and 5 confirmed that they pay annual fees to join the Industrial Association of the Post Industry in the UK, from which they received ‘general’ industrial-related information (e.g., a brief of industrial trends). Using private consultant services is expensive, highlighted by case 1 and case 2 firms who paid more money than case 4 and case 5, but received ‘tailored’ and professional services, typically designed for their companies. The evidence from these 4 cases suggests that the business networks in which to embed in a host country are determined by not only the nature of its business but also how many resources small firms are willing to invest in and can afford.

One of the most interesting cases is that of the owner of the hotel business (case 1) who networked during the start-up stage with a local competitor running a guest house business in the Lake District. It was, from this manager’s perspectives, an effective way to embed his business into the local society. He explained:

‘This village (where his business is located) is small, only about 6,000 people, due to its unique geographic location (one of the most popular tourism areas in the Lake District in the UK), with more than half of the local businesses involved in B&B, guest house or hotel services. They are my competitors but not ‘enemies’! If you can make your competitors accept you as a newly started foreign business, you’ll get much more (knowledge and information) than what you expected …. Her guest house is opposite my hotel, we are neighbors (laugh), she (the owner of the guest house) taught me a lot, to express my appreciation, in return, I introduced customers to her guest house if I had no rooms available during the busy season …’

We further asked this owner-manager how he developed such a network and he pointed out three main reasons: (1) his outgoing personality and good communication skills; (2) his emotional intelligence; (3) his multi-cultural background and knowledge. It was learned that this owner-manager had been studying for 8 years in a British university before he started his own hotel business in the UK. Entrepreneurs’ personal traits, behavior and social cognitive knowledge structure have an inevitable impact in managing its embedding networks in the host country.

In summary, it is evident that Chinese small transnational migrant entrepreneurs chose different social networks to embed in the UK at the start-up stage. Through a variety of networks, they have gained transnational social capital to facilitate their embeddedness in the host country.

Stage two: Institutional embeddedness

Our findings also suggest that different institutions in the home and host country have a significant impact on small Chinese enterprises’ embeddedness in the UK. After passing through the start-up stage of embeddedness, firms placed themselves in certain networks that they chose and moved to the ‘development’ stage in which firms experienced a variety of ‘unexpected’ issues and difficulties. The selected quotes in Table 4 illustrate the embedding difficulties and challenges these small Chinese enterprises encountered at the second stage of the embedding process. We define this stage as ‘institutional embeddedness’ as many failure stories started from a ‘misunderstanding’ of the institutions between the UK and China.

Six cases out of 7 (the exception being case 6) experienced different levels of negative embedding difficulties in the UK, either formally or informally. Although these Chinese firms had already prepared themselves before entering the UK markets, the knowledge and information acquired at the pre-entry stage were insufficient. They underestimated the complexity of the institutions when carrying on their business activities after entry. It is evident that simply implementing the business experience and knowledge they acquired in China into the host-country situations led to failures of further embedding in the host country.

As illustrated in Table 4, case 6 presented an exceptional story. In case 6, the local institutional knowledge of the British deputy manager that they had recruited played a key role, and he contributed significantly to the institutional embeddedness as the following quote demonstrates:

‘I was a lucky person, really lucky, as I hired a British manager who had been working in the electric industry for long time in the UK markets and (he) has exceptional ability and sales experience in this area. I rely on him, maybe too much? (laughing)

Nevertheless, hiring such an experienced general manager was a considerable cost for the case 6 company. It may not be affordable for every small enterprise (or they may be unwilling to do so). Meanwhile, it has a potential risk of creating an over-reliance on this network relationship.

In this stage, our findings show that institutional and regulatory regimes in the UK affected a variety of Chinese transnational enterprises’ business activities and their development after the start-up stage. Formal and informal institutional differences in the host country brought great challenges for these transnational enterprises, and in such a local environment it is not a surprise that these Chinese transnational entrepreneurs seek institutional embeddedness after passing the ‘survival stage.’

Table 4. Selected institutional embeddedness related quotes

|

Cases |

Institutional embeddedness |

|

|

Formal Institutions Informal Institutions |

||

|

Case 1 Case 2 Case 3 Case 4 Case 5 Case 7 |

“I was extremely struggling with maintaining the relationships with English employees. Working slight over time is such a common business practices in China, nevertheless, it did not work here …. I really had problems in managing British people” “The institutional environment in the UK is quite stable and transparent, but regulations are too detailed (comparing with China). If you were not fully prepared for that, you have troubles. I went to the court for several times because of breaking the HR law unconsciously…. that was disaster” Good understanding of the formal institutions (e.g. regulations and policies), and worked closely with his solicitors who was willing to provide many valuable advices “I was fined £2,000 in the first months due to misunderstanding of the local business practices …I did not check a young customer’s ID when he bought cigarette, then I was reported by another customer and was punished” “I sacked one pregnant woman working in my Post Office. She made so many mistakes, I thought that I did everything which I SHOULD do, indeed I neglected some regulations to sack a pregnant woman. I have never, I meant never, thought I had that much trouble later. It was nightmare …. Cannot image how I went through it!” “Running a pub, you must be very sensitive to the regulations, learn all of regulations and laws as quick as possible … it impossible that you ask your solicitor all the time. When something happened emergently, you have to deal with it based on your sense making, but it might be wrong!” |

‘Guanxi is a widely accepted Chinese business culture, I attempted to apply it to my business when dealing with my British employees, once the good relationship was established I expect them to work longer-time during the busy seasons (I pay extra), but I was wrong, British people value work and life balance’ Not experienced specifically “I had strained relations with my British deputy manager. We had many disputes in terms of business practices ….. I realised later it was mainly due to the normal value differences” Not mentioned “We had a regular customer who often bought 4 packs of cigarette every day. I told her that she should reduce the amount of cigarette, she was angry ‘it was none of your business’ I was told. Then, the lady has never back my shop since then” “I had bad relationship with local community at the very beginning – I ever fight with a few British men, I was injured, and my daughter sent me to the local hospital. Now I am sponsoring a local football team in the local community …. Much improved relationship after learning and understanding more British culture and norms” |

Stage three: Cognitive embeddedness

After going through the structure embeddedness and institutional embeddedness stages, these small Chinese enterprises established their relatively stable networks and developed competence in dealing with complex institutions in the UK. Following that, the interviewees admitted that owners of these firms realized the importance of updating their management knowledge and leveraging their capabilities if they expected to embed themselves more deeply and better in the UK. The evidence from our investigated cases suggests that this level of embeddedness is largely driven by the decision-makers’ cognitive knowledge. Thus, we defined it as ‘cognitive embeddedness.’

At this growing-up stage, deep learning in a social context has become critical, and the decision-makers’ knowledge structure and strategic thinking styles were brought into play for further embeddedness. Their inherent and antecedent knowledge have constrained their abilities to expand and sustain their businesses in the host country. ‘Unconsciously,’ one interviewee (case 5) explained: ‘the business knowledge and experience which I obtained in China still habitually affected my decisions in the UK, however, it is proving that I was wrong!’. Another interviewed owner-manager (case 1) added:

‘Running a business in a foreign country is not easy, many unpredictable risks, my knowledge of the past did help me to make decisions, but you cannot highly rely on it, dealing with surprise is about every day learning and rethinking!’

Three interviewees (cases 1, 2 and 5) mentioned, for example, that ‘flexibility’ is a key business practice for small Chinese enterprises in China, nevertheless, when applying this management style into business practices in the UK, ‘you have to know THIS flexibility is not THAT flexibility, British employees interpreted it differently from Chinese…..only continuingly updating your cognitive knowledge can help you to find the ‘balance point’ between the two systems, then adapt it! (case 1)’. Re-created cognitive knowledge plays a crucial role in aiding small Chinese entrepreneurs to firmly embed into the networks in the host country.

At the individual level, Chinese transnational entrepreneurs realized the necessary of re-constructing their knowledge through absorbing new local knowledge and adapting the existing knowledge to gain competitive advantages in the new and dynamic environment. Our findings indicate that Chinese transnational enterprises’ embeddedness is not solely influenced by the networks and institutions in the host country, but is affected by the individuals themselves as they are the key decision-makers for the firms.

A dynamic dual embeddedness process

At the initial stage of the embeddedness, these immigrated entrepreneurs of study case companies used a variety of connections with their networks (e.g. businesses or family ties, etc.) in China to help them in determining which business sectors to start in the UK as the following quotes demonstrate:

‘My family runs an electronic business in China, that’s why I started the same business in the UK (case 6)’; ‘My father has been working in the property industry for a decade, so I was encouraged by him to start a proper agent business here (the UK)(case 3)’; ‘I chose beauty products to start in the UK because I have a close relationship with a large wig manufacturer in my home town (case 2)’.

Indeed, these connections largely affected which networks to embed in when these small Chinese firms initially entered the UK markets (e.g., the different types of industrial associations).

Moving to the development stage, entrepreneurs’ activities became more complicated, and a lack of in-depth formal or informal institutional knowledge encouraged these firms to find a better way of further embedding into the institutional environment in the UK. Continuously, it was claimed by interviewees that they still worked closely with ‘advisors’ and ‘mentors’ in China, who can be their parents, individuals or partners, running businesses in China. They seek specific support and advice from ‘the home countryside’ to identify key differences and similarities of institutional practices between the UK and China. These dynamic, interactive and experimental exercises leveraged these small Chinese firms’ competency and helped them to embed better in the UK.

The interviewee in case 6 explored an interesting story regarding their product development, illustrating how a dual embedding process interactively arose between the UK and China. The interviewed owner in case 6 has run his business in the UK for more than 10 years, and his electronic products were well perceived by British customers. At a local business conference, a potential business partner expressed his interest in their products and said to him: ‘we are currently using French-made products; I am wondering whether we can do business together.” After a few meetings and product tests ‘we were told that the quality of our products could not meet their standard,’ said the owner-manager. On a trip to China, this owner persuaded his father (who runs an electronic business in China as well) to sponsor and support him in developing higher standard products for this potential customer. “We succeeded and had more customers who need high-quality products and this success facilitated not only my business in the UK but my father’s business in China’. This story demonstrates that embeddedness in the host country can be enhanced via interactive business activities between host and home countries.

Our findings in this section suggest that the embeddedness of Chinese transnational entrepreneurs in the UK is a dual process. When they face challenges in the local environment, due to a variety of influencing factors e.g., networks; institutional differences and individual knowledge limitations), they attempted to seek new opportunities and support from the home country. Mixed embeddedness of social and economic activities enhances their performance in both countries.

DISCUSSION

Embeddedness can either “enable or constrain entrepreneurial activities” (McKeever, Jack, & Anderson, 2015, p. 52). Understanding how small entrepreneurial enterprises harvest and embed businesses in their immigrated countries is an important and worthwhile research issue (Johnstone & Lionais, 2004; Uzzi, 1997). However, limited studies have examined this phenomenon, particularly with a focus on small immigrated entrepreneurial enterprises. This research attempts to fill this research gap by presenting the key findings demonstrated in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2. A dual embedding process adapted by small Chinese immigrated firms

Our findings generally support the view that embeddedness has multiple meanings and uses (Bagwell, 2018) and context is recognized as a critical factor in explaining entrepreneurial embeddedness (McKeever, Jack, & Anderson, 2015). Three different types of embeddedness forms were discovered in this research: structure embeddedness; institution embeddedness and cognition embeddedness. First, we found that small entrepreneurial firms make clear decisions about what typical networks to embed in the host country at the start-up stage. Consistent with network theory, firms admitted that embedding into the local social structure helps them to accumulate social capital (Drori, Honig, & Wright, 2009; Mustafa & Chen, 2010). Nevertheless, small firms, in general, suffer from insufficient resources (Ibeh & Kasem, 2011), and facing a variety of networks in the host country must decide where to embed and how to structure their initial networks at the early post-entry stage. Apart from these pre-requested professional networks (e.g., bank, solicitors, accountants, etc.), it appears that Chinese ethnic groups in the UK and government ties are important networks to embed in. This finding can be explained by the ‘Guanxi’ business culture (Dimitratos, Buck, Fletcher, & Li, 2016; Meyer & Peng, 2005) and power distance of Chinese national culture (Hofstede, 1980). It is also evident that to build a social relationship with competitors in the host county is rare (only one case out of 7) and difficult, but it is worth considering. According to the interviewee in case 1, such a network relationship brought him great advantages which helped him to better embed his hotel business in the Lake District region in the UK.

Second, this research argues that institutional embeddedness constitutes a crucial factor in leveraging small entrepreneurial enterprises’ capability and improving their performance in the host country. After choosing what types of networks to structure, soon the small firms found that embedding within these networks was complex and affected by many institutional factors. The formal and informal institutional gaps (rules and regulations; norms and values) between emerging and developed countries (Yamakawa, Peng, & Deeds, 2008; Yeung, 2002) significantly constrained small Chinese entrepreneurial embeddedness in the UK. Our findings show that institutional embeddedness shapes firms’ strategic choice (Rizopoulos & Sergakis, 2010) and influences its embeddedness process in the host country. Our findings support Dimitratos, Buck, Fletcher and Li (2016) who confirmed that Chinese transnational entrepreneurs attempt to achieve legitimacy in relation to the host country’s environment of formal or informal institutions.

Third, at the individual level, the emerged cognition embeddedness reflected entrepreneurs’ awareness of changing their ‘stereotyped thinking mode’ after they encountered difficulties and issues during the institutional embeddedness stage. It seemed that simply and passively applying the prior acquired knowledge or experience into the host country system did not work properly for these small Chinese enterprises. Each entrepreneur has their own cognitive style, and when faced with a new problem in the host country they used the mind methods they were already familiar with (Wickham, 2006). However, the pre-cognitive styles limited them in finding new ways to constitute their business strategy in the host country. Consequently, they were willing, even eager to update their already stored home-country based knowledge through acquiring new host-country based knowledge to find a ‘combined’ approach during the embeddedness process. This learning, skill and expertise development at the growth stage leveraged the entrepreneurs’ capability of creativity and inventiveness and enhanced its local embeddedness. Our findings extend Bagwell’s (2018) embeddedness study by showing, at the micro level, that not just individual and co-ethic resources, but the entrepreneurs’ own background and knowledge also determine transnational migrant entrepreneurs’ embeddedness in the host country.

Fourth, compared to the majority of prior organizational embeddedness studies (Andersson, Björkman, & Forsgren, 2005; Uzzi, 1997), our findings show that embeddedness in the context of transnational entrepreneurship is more complex and dynamic (Dimitratos, Buck, Fletcher, & Li, 2016). An interesting result of this study is the identification of the interactive dual embedding process, involving both home and host countries. This finding extends Granovetter’s (1985) key insight that embeddedness can be an on-going contextualization of economic exchange (activities) in different social structures in the context of transnational migrant entrepreneurship. Our finding reveals that the degree of embeddedness in the host country is affected by already established networks in the home country (Bagwell, 2018). The diversified networks (e.g., the types of transnational ties at different levels: individual and governmental networks) have a substantial impact on the Chinese transnational migrant entrepreneurs’ embeddedness (Brzozowski, Cucculelli, & Surdej, 2017; Urbano, Toledano, & Ribeiro-Soriano, 2011). Taking a small Chinese entrepreneurial enterprise for example (case 6), embeddedness in the host country is developed and facelifted through an interaction of both home and host country networks (Mustafa & Chen, 2010). Overall, our study widens Zukin and DiMaggio’s (1990) and Granovetter’s (1985) concept, who propose that embeddedness refers to the contingent nature of economic activity on cognition, social structure and political institutions in the context of small transnational entrepreneurs attempting to embed their businesses in the host country. Moreover, it supports Bagwell’s (2018) findings that embeddedness of transnational migrant entrepreneurs can be affected by both macro (institutional) and micro levels (individual).

CONCLUSION

This study sought understanding about how transnational migrant entrepreneurs embed their businesses in the host country. The questions explored are what is the embedding process for small transnational enterprise? How do transnational immigrant entrepreneurs embed their businesses successfully in the host country? We found that transnational entrepreneurs focus on different types of embeddedness at different stages, by choosing which networks to embed in at the start-up stage in order to achieve deeper embeddedness via institutional and cognitive embedding process. Migrant entrepreneurs also devote different resources and efforts on certain dimensions due to limited resources and international experiences (Bagwell, 2018). Interestingly, it is not just embedded networks in the host country, but well-established networks in the home country that also provide these entrepreneurs with sources of advice, resource, information and support which contribute to their successful embeddedness in the host country (Elo et al., 2018).

The contribution of our research is two-fold. First, our findings shed light on the theory of embeddedness in the context of transnational entrepreneurship. We have conceptualized the relationship between small transnational enterprises and embeddedness by identifying three different types of embeddedness as a hierarchical process. Very few entrepreneurial studies illustrate how small entrepreneurial firms generate their embedded structure from ‘process’ perspectives. The second contribution of our study lies in its illustration of how networks in the home country affect small entrepreneurial enterprises’ embeddedness in their immigrated host country. It is evident that the interconnectedness between the home country and host country should be taken into consideration in future entrepreneurial embeddedness studies. In this sense, we encourage embeddedness researchers to pay attention to the ‘home country’ factor as well rather than just focusing on the host country as a one-way process in the international embeddedness research domain.

While we claim the contributions, we are aware of the limitations. First, our study is only based on small Chinese entrepreneurial firms operating in the UK market, and the data were only collected by sampling 7 in-depth case studies. Thus, the results should be viewed cautiously when applying our findings to other contexts due to different institutions (Zahra, Wright, & Abdelgawad, 2014). We suggest that future research address this issue by investigating a wide range of transnational entrepreneurial embeddedness from other countries. Second, many studies confirmed that embeddedness may either enable or constrain cross-border economic activities (Uzzi, 1996; Zukin & DiMaggio, 1990), as small enterprises, in general, have a lack of resources, so embeddedness researchers should conduct further studies, investigating how small immigrated enterprises can avoid ‘over-embed’ in the host country to avoid wasting time and limited resources. Thirdly, there is a lack of formal evidence showing to what extent highly skilled transnational migrant entrepreneurs embed in the host country, and how they differentiate their embedding process from other transnational migrant entrepreneurs. Future studies also need to take into consideration the entrepreneurs’ background, skills and character and discover how these differences affect the transnational migrant entrepreneurs’ embedding process.

Acknowledgments

We thank the two reviewers for providing us with valuable and constructive feedback, and also thank the interviewees in the case study companies who provided valuable insights for this research.

References

Andersson, U., Björkman, I., & Forsgren, M. (2005). Managing subsidiary knowledge creation: The effect of control mechanisms on subsidiary local embeddedness. International Business Review, 14(5), 521-538.

Andersson, U., & Forsgren, M. (1996). Subsidiary embeddedness and control in the multinational corporation. International business review, 5(5), 487-508.

Bagwell, S. (2018). From mixed embeddedness to transnational mixed embeddedness: an exploration of Vietnamese businesses in London. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 24(1), 104-120.

Bagwell, S. (2015). Transnational entrepreneurship amongst Vietnamese businesses in London. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 41(2), 329-349.

Bansal, P., & Corley, K. (2011). The coming of age for qualitative research: embracing the diversity of qualitative methods. Academy of Management Journal, 54(2), 233-237.

Basch, L., Schiller, N. G., & Blanc, C. S. (1994). Nations Unbound: Transnational Projects, Postcolonial Predicaments and Deterritorialized Nation-States. Postfach: Gordon and Breach Publishers.

Bruton, G. D., Khavul, S., & Chavez, H. (2011). Microlending in emerging economies: Building a new line of inquiry from the ground up. Journal of International Business Studies, 42(5), 718-739.

Bryman, A. (2003). Quantity and quality in social research. London: Routledge.

Brzozowski, J., Cucculelli, M. & Surdej, A. (2017). The determinants of transnational entrepreneurship and transnational ties’ dynamics among immigrant entrepreneurs in ICT sector in Italy. International Migration, 55(3), 105-125.

Brzozowski, J., Cucculelli, M., & Surdej, A. (2014). Transnational ties and performance of immigrant entrepreneurs: the role of home-country conditions. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 26(7-8), 546-573.

Chen, W., & Tan, J. (2009). Understanding transnational entrepreneurship through a network lens: Theoretical and methodological considerations. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(5), 1079-1091.

Davidsson, P., & Honig, B. (2003). The role of social and human capital among nascent entrepreneurs. Journal of business venturing, 18(3), 301-331.

Dimitratos, P., Buck, T., Fletcher, M., & Li, N. (2016). The motivation of international entrepreneurship: The case of Chinese transnational entrepreneurs. International business review, 25(5), 1103-1113.

Drori, I., Honig, B., & Wright, M. (2009). Transnational entrepreneurship: An emergent field of study. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(5), 1001-1022.

Eisenhardt, K. M., & Graebner, M. E. (2007). Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges. Academy of management journal, 50(1), 25-32.

Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Making fast strategic decisions in high-velocity environments. Academy of Management Journal, 32(3), 543-576.

Elo, M., Sandberg, S., Servais, P., Basco, R., Cruz, A. D., Riddle, L., & Täube, F. (2018). Advancing the views on migrant and diaspora entrepreneurs in international entrepreneurship. Journal of International Entrepreneurship, 16(2), 119-133.

Fontana, A. & Frey, J. (2004). The interview: From structured questions to negotiated text. In N. Denzin & Y. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (2nd Ed.). London: Sage, 645-670.

Forsgren, M., Holm, U. & Johanson, J. (1992). Internationalization of the second degree: the emergence of European-based centres in Swedish firms. In S. Young & J. Hamill (Eds.). Europe and the Multinationals. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Granovetter, M. (1985). Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness. American journal of sociology, 91(3), 481-510.

Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture’s consequences: International differences in work-related values. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

Ibeh, K., & Kasem, L. (2011). The network perspective and the internationalization of small and medium sized software firms from Syria. Industrial Marketing Management, 40(3), 358-367.

Jack, S. L., & Anderson, A. R. (2002). The effects of embeddedness on the entrepreneurial process. Journal of Business Venturing, 17(5), 467-487.

Johnson, L., & Kimmelman, D. (2014). Migrant entrepreneurs: Building our businesses creating our jobs. A report by Centre for Entrepreneurs and DueDil.

Johnstone, H., & Lionais, D. (2004). Depleted communities and community business entrepreneurship: revaluing space through place. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 16(3), 217-233.

Katila, S., & Wahlbeck, Ö. (2012). The role of (transnational) social capital in the start-up processes of immigrant businesses: The case of Chinese and Turkish restaurant businesses in Finland. International Small Business Journal, 30(3), 294-309.

Kenney, M., Breznitz, D., & Murphree, M. (2013). Coming back home after the sun rises: Returnee entrepreneurs and growth of high tech industries. Research Policy, 42(2), 391-407.

Lan, T., & Zhu, S. (2014). Chinese apparel value chains in Europe: low-end fast fashion, regionalization, and transnational entrepreneurship in Prato, Italy. Eurasian Geography and Economics, 55(2), 156-174.

Lee, T. W. (1999). Using qualitative methods in organizational research. Sage Publications.

Ley, D. (2006). Explaining variations in business performance among immigrant entrepreneurs in Canada. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 32(5), 743-764.

Light, I. (2007). Global entrepreneurship and transnationalism. In L. P. Dana (Ed.). Handbook of research on ethnic minority entrepreneurship: A co-evolutionary view on resource management. Edward Elgar Publishing, 3-15.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. California: Sage Publications.

Lin, X., & Tao, S. (2012). Transnational entrepreneurs: Characteristics, drivers, and success factors. Journal of International Entrepreneurship, 10(1), 50-69.

Liu, X., Lu, J., Filatotchev, I., Buck, T., & Wright, M. (2010). Returnee entrepreneurs, knowledge spillovers and innovation in high-tech firms in emerging economies. Journal of International Business Studies, 41(7), 1183-1197.

Mainela, T., & Puhakka, V. (2008). Embeddedness and networking as drivers in developing an international joint venture. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 24(1), 17-32.

Mainela, T., Puhakka, V., & Servais, P. (2014). The concept of international opportunity in international entrepreneurship: a review and a research agenda. International journal of management reviews, 16(1), 105-129.

McDougall, P. P., & Oviatt, B. M. (2000). International entrepreneurship: the intersection of two research paths. Academy of Management Journal, 43(5), 902-906.

McGrath, H., & O’Toole, T. (2014). A cross-cultural comparison of the network capability development of entrepreneurial firms. Industrial Marketing Management, 43(6), 897-910.

McKeever, E., Jack, S., & Anderson, A. (2015). Embedded entrepreneurship in the creative re-construction of place. Journal of Business Venturing, 30(1), 50-65.

Meyer, K. E., & Nguyen, H. V. (2005). Foreign investment strategies and sub‐national institutions in emerging markets: Evidence from Vietnam. Journal of management studies, 42(1), 63-93.

Meyer, K. E., & Peng, M. W. (2005). Probing theoretically into Central and Eastern Europe: Transactions, resources, and institutions. Journal of international business studies, 36(6), 600-621.

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. Sage Publications.

Mustafa, M., & Chen, S. (2010). The strength of family networks in transnational immigrant entrepreneurship. Thunderbird International Business Review, 52(2), 97-106.

Nahapiet, J., & Ghoshal, S. (1998). Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage. Academy of management review, 23(2), 242-266.

Nell, P. C., Ambos, B., & Schlegelmilch, B. B. (2011). The MNC as an externally embedded organization: An investigation of embeddedness overlap in local subsidiary networks. Journal of World Business, 46(4), 497-505.

North, D. (1990). Institutions, institutional change and Economic performance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pavlov, T., Predojević-Despić, J., & Milutinović, S. (2013). Transnational entrepreneurship: Experiences of migrant-returnees to Serbia. Sociologija, 55(2), 261-282.

Peng, M. W., & Heath, P. S. (1996). The growth of the firm in planned economies in transition: Institutions, organizations, and strategic choice. Academy of management review, 21(2), 492-528.

Perren, L., & Ram, M. (2004). Case-study method in small business and entrepreneurial research: mapping boundaries and perspectives. International small business journal, 22(1), 83-101.

Pratt, M. G. (2009). From the editors: For the lack of a boilerplate: Tips on writing up (and reviewing) qualitative research. Academy of Management Journal, 52(5), 856-862.

Pruthi, S. (2014). Social ties and venture creation by returnee entrepreneurs. International Business Review, 23(6), 1139-1152.

Rath, J., & Kloosterman, R. (2000). Outsiders’ business: a critical review of research on immigrant entrepreneurship. International migration review, 34(3), 657-681.

Riddle, L., Hrivnak, G. A., & Nielsen, T. M. (2010). Transnational diaspora entrepreneurship in emerging markets: Bridging institutional divides. Journal of International Management, 16(4), 398-411.

Rizopoulos, Y. A., & Sergakis, D. E. (2010). MNEs and policy networks: Institutional embeddedness and strategic choice. Journal of World Business, 45(3), 250-256.

Sabah, S., Carsrud, A. L., & Kocak, A. (2014). The impact of cultural openness, religion, and nationalism on entrepreneurial intensity: Six prototypical cases of Turkish family firms. Journal of Small Business Management, 52(2), 306-324.

Saxenian, A. (2002). Transnational communities and the evolution of global production networks: the cases of Taiwan, China and India. Industry and innovation, 9(3), 183-202.

Scott, W. R. (1995). Institutions and organizations: Ideas and interests. Los Angeles: Sage Publications.

Sequeira, J. M., Carr, J. C., & Rasheed, A. A. (2009). Transnational entrepreneurship: determinants of firm type and owner attributions of success. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(5), 1023-1044.

Urbano, D., Toledano, N., & Ribeiro-Soriano, D. (2011). Socio-cultural factors and transnational entrepreneurship: A multiple case study in Spain. International Small Business Journal, 29(2), 119-134.

Uzzi, B. (1997). Social structure and competition in interfirm networks: The paradox of embeddedness. Administrative Science Quarterly, 42, 35-67.

Uzzi, B. (1996). The sources and consequences of embeddedness for the economic performance of organizations: The network effect. American sociological review, 674-698.

Wang, K. T., Li, F., Wang, Y., Hunt, E. N., Yan, G. C., & Currey, D. E. (2014). The international friendly campus scale: Development and psychometric evaluation. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 42, 118-128.

Welter, F. (2011). Contextualizing entrepreneurship—conceptual challenges and ways forward. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 35(1), 165-184.

Wickham, P. A. (2006). Strategic entrepreneurship (4th Ed.). Edinburgh: Pearson Education.

Wong, L. L., & Ng, M. (2002). The emergence of small transnational enterprise in Vancouver: The case of Chinese entrepreneur immigrants. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 26(3), 508-530.

Yamakawa, Y., Peng, M. W., & Deeds, D. L. (2008). What drives new ventures to internationalize from emerging to developed economies?. Entrepreneurship theory and practice, 32(1), 59-82.

Yeung, H. W. C. (2002). Entrepreneurship in international business: An institutional perspective. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 19(1), 29-61.

Yinger, J. M. (1985). Ethnicity. Annual Review of Sociology, 11, 151-180.

Yin, R. K. (2003). Case study research: Design and Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Zahra, S. A., & George, G. (2002). The net-enabled business innovation cycle and the evolution of dynamic capabilities. Information Systems Research, 13(2), 147-150.

Zahra, S. A., Wright, M., & Abdelgawad, S. G. (2014). Contextualization and the advancement of entrepreneurship research. International small business journal, 32(5), 479-500.

Zukin, S., & DiMaggio, P. (1990). Structures of capital: The social organization of the economy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Abstrakt

Skuteczne osadzenie w kraju przyjmującym jest ważną kwestią dla przedsiębiorców imigrantów i przedsiębiorców transnarodowych. Wcześniejsze badania z tego obszaru koncentrowały się głównie na lokalnym osadzeniu spółek międzynarodowych (MNCs). Do tej pory badano przedsiębiorstwa ponadnarodowe, i niewiele osób zajmowało się sposobem osadzenia w kraju przyjmującym przedsiębiorców transnarodowych. Opisane badanie oparte jest na 7 pogłębionych studiach przypadku małych, chińskich przedsiębiorstw międzynarodowych działających w Wielkiej Brytanii. Na podstawie analiz Autorzy stworzyli dynamiczny model podwójnego procesu, który składa się z 3 wymiarów: osadzenia strukturalnego; osadzenia instytucjonalnego; i osadzenia poznawczego. Wnioski z badania stanowią teoretyczny wkład, oferując wgląd w sposób, w jaki międzynarodowi przedsiębiorcy migrujący osadzają się w podwójnym, transgranicznym środowisku biznesowym.

Słowa kluczowe: przedsiębiorczość transnarodowa, kraj przyjmujący, teoria instytucjonalna, zakorzenienie

Biographical notes

Rose Quan is a Senior Lecturer of International Business Studies and Strategy, Northumbria University, Newcastle, UK. Her research focuses on international entrepreneurship, and international student and staff mobility. She has served as the module leader of Entrepreneurial Start-Up Programme at the Newcastle Business School for the last 10 years.

Mingyue Fan is an Associate Professor at the School of Management, Jiangsu University, China. Her research interest mainly focuses on information management, social entrepreneurship, entrepreneurial innovation and sustainability.

Michael Zhang is a reader at Nottingham Business School, Nottingham Trent University, UK. His research interest has been focused on three inter-related areas, including international joint ventures; entrepreneurship with a focus on the process of opportunity discovery; and economic development of transition economies.

Huan Sun is a full-time Ph.D. candidate at Newcastle Business School, Northumbria University, Newcastle, UK. Her doctoral research topic is related to Chinese SMEs’ innovation and sustainability. She has also served as an Associate Lecturer at Northumbria University.