Received 9 June 2017; Revised 30 August 2017, 27 December 2017; Accepted 11 January 2018

Muhammad Nawaz, Ph.D. Scholar, Lecturer, National College of Business Administration and Economics, 40-E1, Gulberg III, Lahore 54660, Pakistan, tel. +923217060417, e-mail: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

Ghulam Abbas Bhatti, Ph.D. Scholar, National College of Business Administration and Economics, 40-E1, Gulberg III, Lahore 54660, Pakistan, tel. +923014737094, e-mail: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

Shahbaz Ahmad, MPhi-Mathematics, National College of Business Administration and Economics, 40-E1, Gulberg III, Lahore 54660, Pakistan, tel. +923004807604, e-mail: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

Zeshan Ahmed, 360 GSP Institute of Computer Science, 21 Empire Way London, HA9 0PA, United Kingdom, e-mail: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

Abstract

The purpose of this research is twofold: firstly it was planned to examine the relationship and impact of peer-relationship on organizational commitment by means of and without the moderating role of psychological capital. Secondly, the researchers aimed to examine the association of organizational culture and organizational commitment, similarly, by way of and without the moderating effect of psychological capital. This study is cross-sectional by nature in which data were collected from the operational staff of Pakistan railways. While investigating the moderating impact of psychological capital on the association of peer relationship and organizational commitment, it was found that psychological capital strengthens the relationship of peer relationship and organizational commitment; and also strengthens the relationship of organizational culture and organizational commitment as well.

Keywords: peer relationship, organizational culture, organizational commitment, psychological capital.

INTRODUCTION

The importance of operational staff in any organization is unchallengeable, for instance, operational staff are marketers and salesmen for marketing based organizations; lecturers and professors for colleges and universities; similarly drivers, guards and ticket checkers in railway institutions. As operational staff is directly linked to the main operations of an organization, they should be rich in conceptual, technical and human skills. In this context, the retention of talented and knowledgeable workers has become very difficult and challenging as well (Joo, 2010)43% of the variance in organizational commitment was explained by organizational learning culture and LMX quality. About 40% of the variance in turnover intention was explained by organizational commitment. Thus, perceived organizational learning culture and LMX quality (antecedents, and for the sake of resolution, many organizations attempt to develop employees of choice in this regard. It is no doubt the first priority of every organization to engage the skilled and talented workers in order to establish a positive culture (Sutherland & Dennick, 2002). Furthermore, while taking peer relationships into consideration, a social life sustains an employee in a comfort zone, for instance, Janik, Blaskova & McLellan (2017) expressed friendship, family and sexual intimacy as important in building peer relationships (employee-to-employee relationships) within organizations.

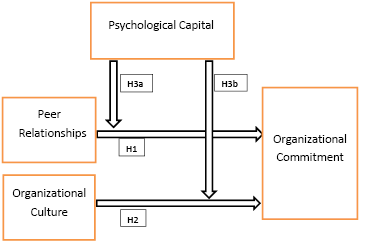

Over the past few decades, intensive research work has been done on organizational culture, peer relationship and organizational commitment. For instance, psychological capital is a predictor of organizational commitment (Shahnawaz & Jafri, 2009) while its moderating role is rarely available. That is one of the reasons why psychological capital as a moderator has been used in this study (see Figure 1).

Peterson and Luthans, (2003) reported a clear link between psychological capital and workplace outcomes. Thus, this study attempts to find the moderating impact of psychological capital. From a practitioner’s perspective, when managers and executive officers of Pakistan railways improve the level of psychological capital of operational staff, which can be enhanced by training and development, what will happen to the level of commitment of Pakistan Railways’ employees? When there is a tight versus loose control culture, and when there exist social peer relationships among the operational staff of Pakistan Railways, then what will happen to the organizational commitment with, and without, the presence of psychological capital? As customer relationship management always attempts to create and retain customers, which helps them build long-term relationships (Nawaz, Nazir, Jamil, Aftab & Razzaq, 2016), the operational staff of Pakistan Railways has a direct impact on passengers. Thereby, operational staff might have a positive influence on customer relationship management. The importance of this study in the context of Pakistan railways, is that organizations play a vital part in the development of the national economy of a country (Javed, Ahmed, Nawaz & Sajid, 2016), and similarly, Pakistan railways, with its monopolistic characteristics, can perform a crucial role in the development of Pakistan’s economy.

While talking about future direction, Lund (2003) examined the relationship between organizational culture and positive workplace outcomes, e.g., job satisfaction and employee commitment, by focusing on knowledge workers with a high educational level. According to Lund (2003), results vary by the cohorts in different educational levels, and a research call shows that more research is required with participants from different educational levels, and hence it will take in this study with a proposed model (Figure 1). According to Gülerüz et al. (2008), cultural impact has been neglected in the same study as a limitation. Hence, these reasons enhance the motivation to investigate this in this study with following questions.

- Does psychological capital strengthen the relationship between organizational culture and organizational commitment?

- Does psychological capital strengthen the relationship between peer relationship and organizational commitment?

LITERATURE REVIEW

Peer relationships in the workplace and organizational commitment

Avery, McKay and Wilson (2007)also known as engagement. Few empirical studies, however, have examined how individual or situational factors relate to engagement. Consequently, this study examines the interplay between employee age, perceived coworker age composition, and satisfaction with older (older than 55 investigated peer relations and their importance in such a way that, due to social relations in the workplace, employees feel comfortable and employees’ feelings of insecurity reduce. Employees’ level of understanding increases and, as a result, they share more information with their peers and their level of commitment increases, which eventually reduces their work-related problems. Social life, even in the workplace or in society, has a great deal of concern and importance. Implicit theories by Molden and Dweck (2006) explored how people perceive and then value social interaction, which can then help us to understand the association between peer relationship and organizational commitment. According to these theories, personal characteristics such as attitude, norms, personal attributes and beliefs are unchangeable.

Galliher and Kerpelman (2012) worked on the character improvement and associated procedure of sexual orientation and other social interaction related factors. It resulted that employees’ motivational experiences support the association between peer relations and their organizational commitment, which leads them towards their goal achievement. A variety of research has been conducted on multiple combinations of peers’ relationships which enhance employees’ motivation, satisfaction and commitment towards their work (Ullrich-French & Smith, 2006, 2009).

In the workplace, there is a need to explore peer relationships and their effects on organizational commitment (Ullrich-French & Smith, 2006). Peer relationship has two dimensions: Peer victimizing and peer rejection (Boivin, Fuller, Dennell, Allaby & Petraglia, 2013): a negative peer status is called peer rejection and a negative peer experience is considered as peer victimizing (Boivin et al., 2013). Thus, as per the above arguments, we can propose that peer relationship has a positive relationship with organizational commitment.

Hence, as per the above arguments, we may propose that:

H1: The relationship between peer relationship and organizational commitment is positive and significant.

Organizational culture and organizational commitment

Van den Steen (2003) argued that constant values, beliefs and behavioral patterns define corporate culture. Corporate culture has been preferably discussed in the previous literature, as in the organizations’ working environment the tasks are being done through organizational culture. Furthermore, it is evident that culture is a dynamic force which develops the environmental settings through its strong relationship with humans (Binder & Baker, 2017). The concerned dimensions of organizational culture in this study are tight versus loose control culture, which is explained by Hofstede (1998)but parts of organizations may have distinct subcultures. The question of what is the proper level for a cultural analysis of an organization is generally handled intuitively. The organizational culture of a large Danish insurance company (3,400 employees who associates them directly with the phenomenon of control activities and cost.

Tight control culture is purely and extremely cost conscious in nature. Accurate dissemination of the set of information about a budgeting and reporting system is also possible in a tight control culture (Merchant, Van Der Stede & Zheng, 2003). On the other hand, innovative cultures are result oriented cultures. Employees get encouragement from their supervisors which guide them in creating new ideas, and ultimately the organization moves towards progress (Hickey, 2017). As per the acknowledgment by Bergman (2006)1997 fruitful results cannot be obtained without understanding the nature of organizational culture. Past studies also revealed a positive relationship between organizational culture, commitment and job satisfaction (Yousef, 2017).

Employees’ reaction in an organization shows their level of commitment, which most importantly depends upon the culture they have in an organization, and this relationship has been investigated before (Martins & Terblanche, 2003). Studies since the 1980’s have been proved to be highly important in minimizing the differences between weak and strong performers, on the basis of an organizational culture which leads employees towards organizational commitment (Kerr & Slocum, 2014). Employees’ devotion towards their work is based on the efficiency of organizing their tasks by the organizing committee (Wasti Arzu, 2005) which is well defined by Wright, Gardner, and Moynihan (2003) and according to the above study, culture is the variable which defines the level of commitment of the different employees with the different skills at workplace. According to Abdul Rashid, Sambasivan and Johari (2003), a study of corporate culture is very important in finding a strong organizational commitment which may lead to better financial performance. Organizational culture defines the different attributes of the employees, e.g., their emotional intelligence, effective commitment, turnover intention and employee engagement which is discussed by Brunetto, Teo, Shacklock and Farr-Wharton (2012). It has also been found that organizational commitment is positively related to adhocracy and clan culture and negatively related to hierarchical culture (Lund, 2003). Hence, as per the above discussion, we may propose that:

H2: There is a positive significant relationship between organizational culture and organizational commitment.

Psychological capital as a moderator

Psychological capital as a core construct is characterized by:

- in order to succeed, persevering toward goals and redirecting paths to goals when necessary (hope);

- to succeed at challenging tasks, having confidence (self-efficacy) to take on and put in the necessary effort;

- “When beset by problems, sustaining and bouncing back and even beyond (resiliency) to attain success” (Luthans, Youssef & Luthans, 2007); and

- making a positive attribution (optimism) about succeeding now and in the future.

Psychological capital is considered as a positive construct and its dimensions are hope, self-efficacy, optimism, and resilience. Individuals are considered as having a high level of psychological capital if they have these four cognitive characteristics mentioned above (Luthans, 2002). In various progressions, the term capital is used in many concepts, for example, human capital, in human resource management, cultural capital in organizational behavior and social capital in economics. Thereby, psychological capital has been conceptually identified by Luthans and Youssef (2004), as well as Luthans, Avolio, Avey, and Norman (2007). In research, the term psychological capital belongs to employees’ motivational properties which are directly related to producing a loose versus tight control culture with the level of employees’ organizational commitment. Employees’ individual psychological capital produces a type of motivational culture (Lopez & Snyder, 2009) which increases their level of job commitment. Further, Avey, Luthans, and Youssef (2010) found that individuals’ psychological capital has a great deal of importance as each of its dimensions is required in an organization to moderate the relationship between organizational culture and organizational commitment.

Psychological Capital has four dimensions; optimism, self-efficacy, hope and resilience, which concern a great part of our study. Stajkovic (2006) carefully hoped that psychological capital would have an impact on employees’ organizational commitment due to these four facets. Extending this statement, the motivational and intellectual level of employees boosts their level of quality of organizational culture with a high psychological capital which eventually leads them towards a higher level of commitment towards their organization (Luthans et al., 2007). Very little research is available on the above relationship between psychological capital and organizational commitment under organizational culture (see Shelton, Gartland, & Stack, 2011). According to the conservation resource model (Hobfoll, 2001) psychological capital, which is the personal resource of an employee, can moderate the association between peer relationship and their organizational commitment. Cheung, Tang and Tang (2011) further investigated the role of psychological capital as a moderating variable to explain the relationship between organizational commitment and peer relationship.

Hence as per the above studies, we may propose that:

H3a: Psychological capital has a moderating effect on the association of peer relationship and organizational commitment.

H3b: Psychological capital has a moderating effect on the association of organizational culture and organizational commitment.

Figure 1. Conceptual model

RESEARCH METHODS

All participants of this empirical research were the operational staff of Pakistan railways that include drivers, guards and ticket checkers having a basic pay scale (BPS-16) from Punjab (Pakistan). 250 questionnaires were circulated and the response rate was 84%. All the participants were men, as females are excluded from being part of the operational staff by Pakistan Railways. Self-administrated questionnaires were distributed. For each item, a 5-point Likert scale was used signifying ‘1’ for “strongly disagree” and ‘5’ for “strongly agree” respectively. The scale consisted of 15-items borrowed from Kanning and Hill (2013) to measure organizational commitment.

Organizational culture was measured with an 8-item scale developed by Baird, Harrison, and Reeve (2004) which explained one dimension of organizational culture that is tight versus loose control. Further, peer relationship was measured with a 17-item scale developed by Slee and Rigby (1994). Further, to measure psychological capital (work self-efficacy, optimism, hope, and resilience) the original 24-item scale developed by Luthans et al. (2007) was used.

HYPOTHESES TESTING AND RESULTS

To check the scale validity of the study variables, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted. The results of 4-variables (organizational culture, peer relationships, PsyCap and organizational commitment) demonstrated a comparative fit index.93, a good fit to the data, X2 (3576) = 7409, standardized root-mean square residual .060, a significantly better fit (ps < .05) with root-mean square error approximation .052 than alternative models and single-factor model in which the focal study construct was variously combined. Further, discriminant validity was assessed to ensure that the average variance shared between each construct and its indicators was greater than the shared variance between that construct and each other construct. Consequently, results from these analyses indicated the adequate scale validity (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). In this study, it has been found that Cronbach’s Alpha ranged from .655 to .930 for all variables which typifies that all instruments in the research are reliable (Table 1).

Table 1. Reliability analysis

|

Variables |

Items |

Cronbach’s Alpha |

Source |

|

Organizational Culture |

8 |

0.817 |

Baird, Harrison & Reeve (2004) |

|

Peer Relationship |

15 |

0.655 |

Slee & Rigby (1994) |

|

Organizational Commitment |

15 |

0.819 |

Kanning & Hill (2013) |

|

Psychological Capital |

24 |

0.930 |

Luthans et al. (2007) |

There were 210 respondents of this study to analyze the hypothesized relationships. There were (167) male respondents, of whom the majority were graduate (130) then undergraduate (35) and very few were post-graduate (02). On the other hand, female respondents were (37) graduate, (6) undergraduate and lastly, there was no female respondent having post-graduate qualification (see Table 2). The respondents’ characteristics revealed that, from the sample, those who were educated could understand the terminologies and language of the instrument.

Mean and standard deviation were calculated in order to better understand the sample characteristics (see Table 3). Psychological capital has a mean (3.1921), which was the highest mean of this study with standard deviation (0.37698). It means most of the respondents have high psychological capacities (hope, confidence, optimism, and resilience).

Table 2. Respondent characteristics

|

Variables |

Undergraduates |

Graduates |

Post-Graduates |

Total |

|

Male |

35 |

130 |

2 |

167 |

|

Female |

6 |

37 |

0 |

43 |

|

Total |

41 |

167 |

2 |

210 |

Conversely, the low mean score of organizational commitment and peer relationship (2.6917 and 2.2819 respectively) revealed that there is lack of trust level, friendly environment, sharing, helping environment, etc. Further, a low mean of organization commitment revealed that Pakistan Railways’ employees lack loyalty and care about the company, etc.

To further test the hypothesis of this study, correlation and regression were deployed. From the correlation table given below all four variables are positively correlated with a significance level of (p<0.01). Peer relationship has much correlation with a significance level as given (r=0.531, p<0.01), while Organizational culture has a comparatively low but moderated correlation with organizational commitment (r=0.493, p<0.01).

Table 3. Descriptive statistics

|

Variables |

Minimum |

Maximum |

Mean |

Standard Deviation |

|

Organizational Culture |

1.38 |

4.63 |

3.0054 |

0.72798 |

|

Organizational Commitment |

1.40 |

4.07 |

2.6917 |

0.51029 |

|

Psychological Capital |

1.75 |

4.58 |

3.1921 |

0.84176 |

|

Peer Relationship |

1.73 |

3.60 |

2.2819 |

0.37698 |

The correlation between psychological capital and organizational commitment is also significant (r=0.377, p<0.01). The correlations and significances of the concerned variable were discussed.

Table 4. Correlation analysis

|

Variables |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

|

1 |

Organizational Culture |

1 |

|||

|

2 |

Organizational Commitment |

0.493** |

1 |

||

|

3 |

Psychological Capital |

0.565** |

0.377** |

1 |

|

|

4 |

Peer Relationship |

0.253** |

0.531** |

0.434** |

1 |

**p<0.01

From the correlation table (see Table 4) we can see that there is a significant impact of peer relationships and organizational culture on organizational commitment. To further check the unit change in the dependent variable from the predictors, we applied regression analysis in this regard. Linear regression (Table 5), i.e., model 1, where organizational culture is the predictor and organizational commitment is the outcome, revealed that one unit change in organizational culture brings a 0.493 unit change in organizational commitment and the model is significant (β=0.493, F=66.65, p<0.01, R2=0.243). Further, linear regression in model 2, where peer relationship is the predictor and organizational commitment is the outcome, revealed that one unit change in peer relationship brings about a 0.531 change in organizational commitment; a bit higher than change due to organizational culture, and this model is significant as well (β=0.531, F=81.88, p<0.01, R2=0.282).

The model is significant in the presence of psychological capital with a change in the coefficient of determination (ΔR2 =0.014) showing a 1.4% overall change in organizational commitment, when psychological capital is added, in the association of organizational culture and organizational commitment.

Table 5. Linear regressions

|

Variable |

R2 |

β |

F |

F-sig |

|

Organizational Culture |

0.243 |

0.493** |

66.65 |

0.000 |

|

Peer Relationship |

0.282 |

0.531** |

81.884 |

0.000 |

|

Psychological Capital |

0.142 |

0.77** |

34.537 |

0.000 |

Note: dependent variable - Organizational Commitment.

**p<0.01

Thereby, our hypothesis H3a is supported and brings a YES answer to our research question: Does psychological capital strengthen the relationship between organizational culture and organizational commitment?

Similarly, to check whether psychological capital moderates the association of peer relationship and organizational commitment, linear regression was used, which depicts that psychological capital acts as a significant moderator between peer relationship and organizational commitment (β= -0.311, p<0.05). The overall change of 5.1% in organizational commitment occurs in the presence of the moderator psychological capital. Thus, hypothesis H3b is accepted as well.

Furthermore, from Table 7, the interaction term, i.e. Peer Relationships × Psychological Capital is significant, which revealed that psychological capital has a moderating impact on the association of peer relationships and organizational commitment.

Table 6. Moderation analysis of organizational culture

|

Variables |

Outcome |

|||

|

Organizational Commitment |

||||

|

β |

R2 |

F-sig |

ΔR2 |

|

|

Independent |

0.257 |

0.000 |

0.014 |

|

|

Organizational Culture |

0.327* |

|||

|

Moderator |

||||

|

Psychological Capital |

0.118 |

|||

|

Interaction |

||||

|

Organizational Culture × Psychological Capital |

0.011* |

|||

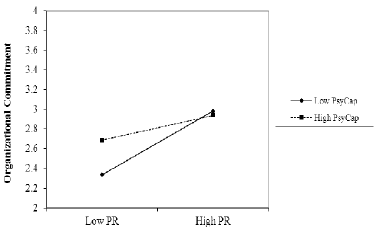

Moreover, the intensity of moderation, with the condition when there is a high level of psychological capital and when there is a low level of psychological capital, can be viewed from the moderation line graph given below (Figure 2).

Table 7. Moderation analysis with peer relationships

|

Variables |

Outcome |

|||

|

Organizational Commitment |

||||

|

β |

R2 |

F-sig |

ΔR2 |

|

|

Independent |

0.333 |

0.000 |

0.051 |

|

|

Peer Relationship |

1.589 |

|||

|

Moderator |

||||

|

Psychological Capital |

0.801 |

|||

|

Interaction |

||||

|

Peer Relationships × Psychological Capital |

-0.311* |

|||

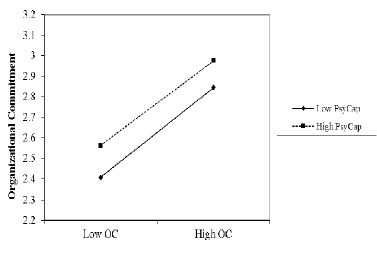

Accordingly, hypothesis H3b of the study was supported. Moreover, the intensity of this moderation, with the condition when there is a high level of psychological capital and when there is a low level of psychological capital, can be viewed from the moderation line graph given below (Figure 3).

Figure 2. The moderation line graph (1)

Figure 3. The moderation line graph (2)

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

The organizational commitment of employees has been chosen as the dependent variable in our study. This study concludes that the possible factors are peer relationships and organizational culture which influence the three most common aspects of organizational commitment; continuous, normative and affective. We test the moderation (cross-level interactions) of psychological capital with peer relationships and the organizational culture of the selected candidates on commitment. Moderation findings demonstrate that low psychological capital creates a weak impact of peer relationships on organizational commitment while the high psychological capital creates a strong impact of peer relationships on organizational commitment. Conversely, the condition of high psychological capital acts as an enhancer between the association of peer relationships and organizational commitment. For example, when employees are equipped with psychological capital, then peer relationships enhance employees’ level of commitment more and vice versa. Further, a stage comes where even with a high level of psychological capital the employee commitment toward an organization becomes reduced, as compared to when there is a low level of psychological capital in employees, this condition engenders when there exists a high level of peer relationships among employees (See Figure 2, the point of intersection).

Conversely to that, there is no point of intersection between two lines (see Figure 3) which revealed that when there is a tight control culture and when there is a loose control culture at low and high psychological capital, the organizational commitment increases with almost equal intensity and slope. Thus, executive officers and other decision-makers, should be generous in their understanding and acknowledgment of the fact that if their employees are equipped with psychological capital, it means they are equipped with the cognitive states of hope, resilience, self-efficacy and optimism, then the impact of peer relationships of Pakistan railways’ operating staff on their commitment to Pakistan railways can be improved to an extent. Furthermore, the executive officers of Pakistan railways should create a tight control culture which produces a higher level of psychological capital in employees, and in return, this will increase the commitment of the operating staff of Pakistan railways as well (here low OC revealed a loose control culture and high OC revealed a tight control culture, see Figure 2).

Consequently, organizational commitment leads to more revenue and profit (Pinho, Rodrigues, Dibb & Rodrigues, 2014) as Pakistan Railways has made a loss for almost the last three decades (Khalid, Nasir & Rameezmohsin, 2016) and this could be minimized or converted into a profit using this concept. Managers should try to improve psychological capital to enhance the impact of peer relationships on their commitment. Since subordinates are on the frontline and have first-hand experience with the customers (Özduran & Tanova, 2017), thereby their opinions should especially be taken into consideration.

It is very likely that subordinates provide critical information to their managers. This information can help them in improving their employees’ peer relationships level with the help of psychological capital. Some aspects such as training intervention (Avey, Reichard, Luthans & Mhatre, 2011), creating a supportive climate (Norman, Avey, Nimnicht & Graber Pigeon, 2010), and authentic leadership, is necessary for smaller as well as larger organizations to improve their employees’ psychological capital. We recommend that managers should consistently develop clear policies and procedures regarding rewards to employees to create and improve psychological capital. Further, the employees should also be allowed (transformational leadership) to express their feelings and opinions regarding decisions, due to which their quality of work-life can improve, which in turn leads to an improved tight control culture, along with the development of rules and procedures.

RECOMMENDATIONS AND LIMITATIONS

This research study has been divided into three phases. In the first phase, the relationship between organizational culture, peer relationship and organizational commitment was investigated, which depicted that an employee’s commitment highly depends upon culture and employees’ social interactions with their co-workers (peer relationships). In the second phase, it was investigated whether psychological capital has a moderating influence on the association of peer relationship and organizational commitment. Moreover, in the third phase, the impact of psychological capital was investigated as a moderating variable between organizational culture and employees’ commitment. This study is limited, in that the checking of dimension wise relations was not the concern of this study, and thus future studies could investigate dimensions. Furthermore, a moderating role of psychological capital has been verified from the significance of the interaction term, but it would be better if the moderating role could be empirically verified through structural equation modeling (SEM). Thus, future studies could apply SEM while working with the same model in other domains, context, or units of analysis (sample). Therefore, what happens next in Pakistan railways, when employees (operating staff) get committed to their organization, could be an area of interest for future researchers. Future studies should also try to collect data by means other than a self-reported survey because self-reported surveys cause common method biases.

This study is cross-sectional in nature; it considered specifically targeted employees (operating staff) of Pakistan railways while results may be different for other employees of Pakistan railways. Thus, future studies could check the conceptual model of this study on employees other than operating staff. Furthermore, future studies may adopt a longitudinal method for dealing with such issues. This study is not exhaustive and that is why it could be considered as incomplete. The possibility of other mediator and moderator variables, such as psychological empowerment, challenging stressors and job characteristics, may overwhelm this limitation.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our warm thanks to Dr. Ghulam Abid and Dr. Alia Ahmed who supported us at every point along the way, and without whom it would have been impossible to accomplish the end result in such a successful manner. Moreover, especially, their conceptual contribution is highly appreciated.

References

Abdul Rashid, Z., Sambasivan, M., & Johari, J. (2003). The influence of corporate culture and organizational commitment on performance. Journal of Management Development, 22(8), 708–728.

Avery, D. R., McKay, P. F., & Wilson, D. C. (2007). Engaging the aging workforce: The relationship between perceived age similarity, satisfaction with coworkers, and employee engagement. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(6), 1542–1556.

Avey, J. B., Luthans, F., & Youssef, C. M. (2010). The additive value of positive psychological capital in predicting work attitudes and behaviors. Journal of Management, 36(2), 430–452.

Avey, J. B., Reichard, R. J., Luthans, F., & Mhatre, K. H. (2011). Meta-analysis of the impact of positive psychological capital on employee attitudes, behaviors, and performance. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 22(2), 127–152.

Baird, K. M., Harrison, G. L., & Reeve, R. C. (2004). Adoption of activity management practices: A note on the extent of adoption and the influence of organizational and cultural factors. Management Accounting Research, 15(4), 383–399.

Bergman, M. E. (2006). The relationship between affective and normative commitment: Review and research agenda. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 27(5), 645–663.

Binder, S. B., & Baker, C. K. (2017). Culture, local capacity, and outside aid: A community perspective on disaster response after the 2009 tsunami in American Sāmoa. Disasters, 41(2), 282-305.

Boivin, N., Fuller, D. Q., Dennell, R., Allaby, R., & Petraglia, M. D. (2013). Human dispersal across diverse environments of Asia during the Upper Pleistocene. Quaternary International, 300, 32–47.

Brunetto, Y., Teo, S. T. T., Shacklock, K., & Farr-Wharton, R. (2012). Emotional intelligence, job satisfaction, well-being and engagement: Explaining organisational commitment and turnover intentions in policing. Human Resource Management Journal, 22(4), 428–441.

Cheung, F., Tang, C. S., & Tang, S. (2011). Psychological capital as a moderator between emotional labor, burnout, and job satisfaction among school teachers in China. International Journal of Stress Management, 18(4), 348–371.

Güleryüz, G., Güney, S., Aydın, E. M., & Aşan, Ö., (2008). The mediating effect of job satisfaction between emotional intelligence and organisational commitment of nurses: A questionnaire survey. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 45(11), 1625–1635.

Galliher, R. V., & Kerpelman, J. L. (2012). The intersection of identity development and peer relationship processes in adolescence and young adulthood: Contributions of the special issue. Journal of Adolescence, 35(6), 1409–1415.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18, 39–50.

Hickey, D. L. (2017). Supervisors: As leading indicators of safety performance. Professional Safety, 62(4), 41.

Hobfoll, S. E. (2001). The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Applied Psychology, 50(3), 337–421.

Hofstede, G. (1998). Identifying organizational subcultures: An empirical approach. Journal of Management Studies, 35(1), 1–12.

Javed, S. A., Ahmed, F., Nawaz, M., & Sajid, A., (2016). Identification of the organizational and managerial characteristics of organizations operating in project conducive environment – A preliminary study. Durreesamin Journal, 2(1), n/a.

Janik Blaskova, L., & McLellan, R. (2017). Young people’s perceptions of wellbeing: The importance of peer relationships in Slovak schools. International Journal of School & Educational Psychology, 1-13.

Joo, B. K. (2010). Organizational commitment for knowledge workers: The roles of perceived organizational learning culture, leader-member exchange quality, and turnover intention. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 21(1), 69–85.

Kanning, U. P., & Hill, A. (2013). Validation of the Organizational Commitment Questionnaire ( OCQ ) in six languages. Journal of Business and Media Psychology, 4(2), 1–12.

Kerr, J., & John W. Slocum, J. (2014). Managing through corporate culture reward systems. The Academy of Management Executive (1993-2005), 19(4), 130–138.

Khalid, A., Nasir, M., & Rameezmohsin, M. (2016). Why Pakistan railways has failed to perform : A special focus on passenger perspective. Journal of the Research Society of Pakistan; Lahore, 53(2), 20–32.

Lopez, S. J., & Snyder, C. R. (2009). Oxford Handbook of Positive Psychology. Retrieved from http://books.google.com/

books?hl=en&lr=&id=NWF-AwAAQBAJ&pgis=1

Lund, D. B. (2003). Organizational culture and job satisfaction. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 18(3), 219–236.

Luthans, F. (2002). Positive organizational behavior: Developing and managing psychological strengths. Academy of Management Executive, 16(1), 57–72.

Luthans, F., Avolio, B. J., Avey, J. B., & Norman, S. M. (2007). Positive psychological capital: Measurement and relationship with performance and satisfaction. Personal Psychology, 60, 541–572.

Luthans, F., & Youssef, C. M. (2004). Human, social, and now positive psychological capital management: Investing in people for competitive advantage. Organizational Dynamics, 33(2), 143–160.

Luthans, F., Youssef, C. M., & Luthans, F. (2007). Emerging positive organizational behavior. Journal of Management, 33, 321-349.

Martins, E. C., & Terblanche, F. (2003). Building organisational culture that stimulates creativity and innovation. European Journal of Innovation Management, 6(1), 64–74.

McClelland, G. H., & Judd, C. M. (1993). Statistical difficulties of detecting interactions and moderator effects. Psychological Bulletin, 114(2), 376–390.

Merchant, K. A., Van Der Stede, W. A., & Zheng, L. (2003). Disciplinary constraints on the advancement of knowledge: The case of organizational incentive systems. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 28(2–3), 251–286.

Molden, D. C., & Dweck, C. S. (2006). Finding “meaning” in psychology: A lay theories approach to self-regulation, social perception, and social development. American Psychologist, 61(3), 192–203.

Nawaz, M., Nazir, B., Jamil, M., Aftab, J., & Razzaq, M. (2016). Service quality in public and private hospitals in Pakistan: An analysis using SERVQUAL model. Apeejay-Journal of Management Sciences and Technology, 4 (1), 13-25.

Norman, S. M., Avey, J. B., Nimnicht, J. L., & Graber Pigeon, N. (2010). The interactive effects of psychological capital and organizational identity on employee organizational citizenship and deviance behaviors. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 17(4), 380–391.

Özduran, A., & Tanova, C. (2017). Manager mindsets and employee organizational citizenship behaviours. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 29(1), 589–606.

Peterson, S. J., & Luthans, F. (2003). The positive impact and development of hopeful leaders. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 24(1), 26–31.

Pinho, J. C., Rodrigues, A. P., Dibb, S., & Rodrigues, A. P. (2014). The role of corporate culture, market orientation and organisational commitment in organisational performance. The case of non-profit organisations. Journal of Management Development, 33(4), 374–398

Schein, E. H. (1996). Culture: The missing concept in organization studies. Administrative Science Quarterly, 41(2), 229.

Shelton, C., Gartland, M., & Stack, M. (2011). The impact of organisational culture and person-organisation fit on job satisfaction and organisational commitment in China and the USA. International Journal of Management Development, 1(1), 15–39.

Stajkovic, A. D. (2006). Development of a core confidence-higher order construct. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(6), 1208–1224.

Sutherland, D., & Dennick, R. (2002). Exploring culture, language and the perception of the nature of science. International Journal of Science Education, 24(1), 1–25.

Ullrich-French, S., & Smith, A. L. (2006). Perceptions of relationships with parents and peers in youth sport: Independent and combined prediction of motivational outcomes. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 7(2), 193–214.

Ullrich-French, S., & Smith, A. L. (2009). Social and motivational predictors of continued youth sport participation. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 10(1), 87–95.

van den Steen, E. (2003). On the origin and evolution of corporate culture preliminary and incomplete. Retrieved from https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/d528/a634fb712e6b645637079e2488e7aefccd7a.pdf

Wasti Arzu, S. (2005). Commitment profiles: Combinations of organizational commitment forms and job outcomes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 67(2), 290–308.

Wright, P. M., Gardner, T. M., & Moynihan, L. M. (2003). The impact of HR practices on the performance of business units. Human Resource Management Journal, 13(3), 21–36.

Yousef, D. A. (2017). Organizational commitment, job satisfaction and attitudes toward organizational change: A study in the local government. International Journal of Public Administration, 40(1), 77-88.

Abstrakt

Niniejsze badania realizują dwa główne cele. Pierwszym z nich było zbadanie związku i wpływu wzajemnych relacji pracowników na ich zaangażowanie organizacyjne przy dwóch założeniach: uwzględnieniu i braku uwzględnienia moderującej roli kapitału psychologicznego. Za drugi z celów przyjęto zbadanie związku kultury organizacyjnej i zaangażowania organizacyjnego, przy tych samych dwu założeniach. Niniejsze badanie ma charakter przekrojowy, w którym zbierano dane od kadry zarządzającej kolei w Pakistanie. Podczas badania moderującego wpływu kapitału psychologicznego na związek wzajemnych powiązań i zaangażowanie organizacyjne, okazało się, że kapitał psychologiczny wzmacnia relacje partnerskie i zaangażowanie organizacyjne, a także wzmacnia związek kultury organizacyjnej i zaangażowania organizacyjnego.

Słowa kluczowe: relacje partnerskie, kultura organizacyjna, zaangażowanie organizacyjne, kapitał psychologiczny.

Biographical notes

Muhammad Nawaz has been working as a Lecturer at the school of business administration, National College of Business Administration & Economics (NCBA&E) since March 2015. He has completed the course work for his Ph.D. (Business Administration) from NCBA&E, and his MS (Business Administration) major Marketing from NCBA&E, and is proficient in using SPSS and AMOS.

Ghulam Abbas Bhatti has been working as a Lecturer at the Department of Business Administration, University of the Punjab Gujranwala Campus since January 2016. Before joining Punjab University, he was working as a Lecturer at National College of Business Administration and Economics, Lahore as a permanent part of the faculty and also as visiting faculty at University of the Punjab, Gujranwala Campus and in different private universities in Lahore. He achieved his Bachelor’s Degree in commerce from Hailey College of Commerce, University of the Punjab, Lahore and then he completed his MS/M.Phil. Degree in Marketing from National College of Business Administration and Economics, Lahore. Currently, he is doing his Ph.D. His coursework in Ph.D. has been completed. His major area of interest lies in Marketing Research. Five of his research papers have been published in renowned international journals. He is proficient in using various packages of research such as SPSS and AMOS. He has been teaching Marketing and Management related courses at undergraduate and postgraduate levels since January 2012.

Shahbaz Ahmad has completed his MSc. Mathematics from National College of Business Administration & Economics. He is currently working as GOVT Teacher at GOVT Gohawa High School, Lahore, Pakistan. He has recently completed his coursework for M.Phil. Mathematics and is now doing his Thesis with enthusiasm. He is excellent in analysis and interpretation portion of the quantitative research.

Zeshan Ahmed received his MBA in Marketing from The University of Lahore, Pakistan. He is currently a student at the 360GSP institute in the UK and is also studying project management and business analysis with Careerinsights UK.