Mohammad Zarei, M.Sc. of Corporate Entrepreneurship, University of Tehran, Faculty of Entrepreneurship, Department of Corporate Entrepreneurship, Farshi Moghadam (16 St.), North Kargar Ave., Tehran 14174-66191, Iran; e-mail: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

Abstract

The notions and motivations of inter-organisational rivalries among employees have to some extent been highlighted by classical theories of management such as tournament theory. However, employees’ and entrepreneurs’ competitions are fundamentally different in pattern. Based on the doctrine of entrepreneurship, entrepreneurial competitions are essential for a productive economy. Even so, there have been few in-depth holistic attempts to understand the rivalry process among corporate entrepreneurs. During the last three decades, various fragmented studies have been conducted from different standpoints to clarify the process of corporate entrepreneurship (CE). Nevertheless, considerable room remains for developing a model of the rivalry process with respect to entrepreneurial activities within large and complex organisations. Hence, the main contribution of the research can be claimed as investigating and formulating the rivalry process. For this purpose, a systematic qualitative grounded theory methodology (GTM) was used. During a five-month period, corporate entrepreneurs from one of the chief Iranian research institutes were systematically interviewed. Based on the research results, in addition to endorsing the existence of such a rivalry process among corporate entrepreneurs, the GTM model extends the literature of CE by examining the previously unaddressed part of the process, i.e., disclosing the corporate entrepreneurs’ implemented strategies, among other blocks of the theory.

Keywords: corporate entrepreneurship; entrepreneurial competition; entrepreneurial tournaments; tournament theory; grounded theory methodology.

INTRODUCTION

Launching an array of strategies to exploit individuals’ intangible assets, or so-called human capital, has been a bottleneck for enterprises. A rich human capital is related to generating further value (Prajogo & Oke, 2016) and furthermore, it is vital for sustainable competitive advantage (Haanes & Fjeldstad, 2000; Hall, 1993; Pearson, Pitfield & Ryley, 2015; Petrick, Scherer, Brodzinski & Quinn, 1999). In this regard, stimulating corporate entrepreneurship (CE) is recommended as an important goal (Covin & Miles, 1999; Teng, 2007), for which the first step is to understand how the entrepreneurial process functions.

Highlighting the entrepreneurial process is vital since firstly, economic ideologies claim that the market, as the heart of the economy, is governed by chains of cause and effect, which are moderated by entrepreneurs, and as a result, entrepreneurial behaviours should be carefully studied (Kirzner, 2017). Secondly, almost half of all entrepreneurial initiatives are doomed to failure. Monk (2000) pointed out that, within the first five years, the failure rates among USA businesses with five or fewer employees and with five to 99 employees were 68% and 48%, respectively. Therefore, scrutinising the entrepreneurial process with the aim of diagnosing impediments to progress and creating fruitful entrepreneurial ventures, is crucial.

Due to the above-mentioned necessities, corporate entrepreneurs’ behaviours and processes have been examined in various ways over the last decades. Some of these initiatives are briefly discussed as follows. As one of the pioneers in understanding the process, Burgelman (1983) integrated the literature on entrepreneurship in organisations from a strategic viewpoint and provided a conceptual integration of CE. The study drew attention to the main prerequisites for fruitful CE, such as organisational structure and learning. In another attempt, McFadzean, O’Loughlin, and Shaw (2005) tried to synthesise the information gathered from previous literature using a holistic approach, in search of a clarification of the connections between corporate entrepreneurial activity and the innovation process. The research led to the development of a framework, based on which corporate entrepreneurs were considered to be in mutual relationships with three principal variables: strategic, external and internal variables. Among the internal variables, several factors are considered, for example: personal fitness, knowledge and experience, opportunity, initial encouragement, need for reassignment and change, resources, planning horizons, support and so on. Hayton (2005), in pursuit of a theoretical explanation for the effect of HRM in providing a proper atmosphere for emerging CE, developed two interdependent themes: encouragement of discretionary entrepreneurial contributions and acceptance of risk. CE has also been investigated in the governmental sector. For instance, Kearney, Hisrich, and Roche (2007), by developing a model of CE within the public sector, suggest that corporate entrepreneurs’ characteristics such as innovation, risk-taking and proactivity are influenced by two leading surrounding environments: external and organisational contexts. In addition, the roles of some components have been emphasised as important for encouraging fruitful CE, for example: the political component, complexity, control, rewards and motivations and so forth. Kuratko (2007), by proposing an extensive model of CE shows how the process of CE functions, including external triggers, strategies, organisational factors, managerial factors, individual elements, outcomes and consequences. Salary increases and promotions, for instance, are mentioned as the managerial outcomes of the process.

Knowledge of CE is to some extent fragmented, and despite our expanding awareness of CE (Ireland, Covin & Kuratko, 2009), holistic studies with a focus on the connection between the divided parts may provide ways to assemble the fragments; for this reason, researchers have lately attempted studies of entrepreneurship using a process approach, (e.g., De Lurdes Calisto & Sarkar, 2017; Mavi, Mavi & Goh, 2017). However, none of the above-mentioned models or studies has considered how corporate entrepreneurs within an organisation compete with one another.

The current research presumes that despite the existence of competition amongst corporate entrepreneurs in an organisation, such entrepreneurial competitions or tournaments have not been maturely defined or investigated; they have merely been mentioned by a few authors, (e.g., Low, Venkataraman & Srivatsan, 1994).

It is generally assumed that competition occurs to obtain resources (Barney, 2001; Chapman & Valenta, 2015; Dierickx & Cool, 1989; Koenig, 2002; Milinski & Parker, 1991; Rodrigues, Duncan, Clemente, Moya-Larano & Magalhaes, 2016), and especially to obtain scarce or valuable resources (Barney, 2001). A number of authors have investigated competition among employees, (e.g., Haan, Offerman & Sloof, 2015; Lazear, 1989; Van Ours & Ridder, 1995), and as a result, the motivational factors in such competitions have been revealed: for instance, winning prizes. In this regard, Gill and Prowse (2014) found that competition in a promoted tournament for winning a prize is a ubiquitous phenomenon in the labour market. Delfgaauw, Dur, Sol and Verbeke (2013), by observing 128 Dutch retail chain stores, deduced that conducting a sales competition among employees has a significant effect on sales growth, and that employees are not motivated only by the aim of gaining more rewards, but also, by winning the competition, as predicted by so-called tournament theory. Lazear and Rosen (1981) in the early 1980s coined the term “tournament theory” in the context of labour microeconomics. The theory was advanced for the purposes of illuminating the differences between individuals’ wages and marginal productivity. Based on the theory, employees of an organisation at the same level participate in competitions or tournaments for promotion, and they engage in a rivalry process to further their career. At the end of each tournament there will be only one winner, who will be greatly rewarded – the so-called winner-takes-all outcome. Although there will be only one winner, interestingly, other employees enthusiastically engage in the tournaments.

On the one hand, the theory does not offer further explanation about the rivalry process amongst employees (Azevedo, Akdere & Larson, 2013). On the other hand, there are unique dissimilarities between employees and corporate entrepreneurs or even between one corporate entrepreneur and another. Zahra and Covin (1995) and Zahra (1993) have comprehensively considered these differences. Apart from the above-mentioned issues, academics still hope to generate a general theory of entrepreneurial competition by conducting further research to examine the entrepreneurs’ strategies and their consequences (Miles, Paul & Wilhite, 2003).

Takii (2009) argues that because entrepreneurs simultaneously recognise similar opportunities, they constantly find themselves in a dynamic competition based on grasping those opportunities. Current research with a multidisciplinary approach goes further and applies tournament theory to CE, assuming that corporate entrepreneurs in an organisation participate in a series of rivalry tournaments, in a similar way to the employees. The rivalry tournaments between corporate entrepreneurs in an organisation are triggered by a combination of organisational and personal requirements. In addition, the research supposes that at the end of each entrepreneurial tournament there will be just one winner, a corporate entrepreneur who will be highly compensated and probably given an opportunity for promotion.

If the above-mentioned hypotheses are accurate, we still know little about the process of entrepreneurial tournaments, and even less about the strategies that are applied by corporate entrepreneurs to win these tournaments. Thus, the four main hypotheses of this research are presented as follows:

- 1) What factors trigger entrepreneurial tournaments within an organisation?

- 2) Secondly, what factors affect the processes of entrepreneurial tournaments?

- 3) Thirdly, what strategies are used by corporate entrepreneurs to win entrepreneurial tournaments?

- 4) Fourthly, what are the outcomes and the advantages and disadvantages of participating in entrepreneurial tournaments?

The remaining sections of the paper are organised as follows: First, the literature on the concept of entrepreneurship is reviewed together with the literature from which the notion of CE and its elements is derived. Second, tournament theory is discussed as the theoretical foundation of the study and its aims, and entrepreneurial tournaments are illustrated. Third, statistical populations and the method of gathering data are explained in the methodology section. In the final section, the results and their implications are presented.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Entrepreneurship

While the term “entrepreneurship” was coined for the first time by Richard Cantillon, the concept itself is as old as the first trading between tribes and villages, going back more than 250 years ago (Austin, Stevenson & Wei-Skillern, 2006). Klein and Bullock (2006) argue that entrepreneurship is theoretically rooted in the theory of economic development proposed by Schumpeter (1911; 1939), the explanations of profit and the firm given by Knight (1921), the market process discussed by Kirzner (1973; 1979; 1992) and the theory of technological adoption and diffusion proposed by Schultz (1975; 1979; 1982). In one sense, entrepreneurship is seen as the respected heritage of the Austrian school of economics, which emphasised the study of the actions of individuals. Based on this school of thought, the market is a dynamic process that is determined by entrepreneurs. Kuratko (2005) defines the term as a dynamic process of vision, change and creation, which requires passion and energy in the direction of creating and implementing new ideas. Furthermore, an entrepreneur accepts risk, needs to think creatively and requires a sufficiency of resources and an efficient mechanism for recognising opportunities. In fact, despite the general idea that entrepreneurship is all about launching a new enterprise, entrepreneurship is actually about “creating value” via a systematic process that is often misunderstood. Therefore, it can be studied in terms of various themes, for instance: social entrepreneurship (Austin, Stevenson & Wei-Skillern, 2006; Zarei, Zarei & Ghapanchi, 2017), SME entrepreneurship (Linán & Chen, 2009; Zarei, Jamalian & Ghasemi, 2017), international entrepreneurship (McDougall, 1989), governmental entrepreneurship (Purwaningsih, 2015), high-tech entrepreneurship (Zarei, Mohammadian & Ghasemi, 2016; Zhou & Peng, 2008) and last but not least, corporate entrepreneurship (Kuratko, Hornsby, Naffziger & Montagno, 1993; Shepherd, Covin & Kuratko, 2009; Zahra, 1991).

Corporate entrepreneurship (CE)

From time to time, CE is expressed as organisational venturing. It was terminologically defined in the middle of the 1990s (Sharma & Chrisman, 1999). CE is generally defined as the activities that an established enterprise (Douglas & Fitzsimmons, 2013; Zahra, 2015) undertakes to enhance the organisation’s production, innovation, risk-taking and proactive response to environmental forces (Castrogiovanni, Urbano & Loras, 2011), and hence, CE can be seen as a series of initiatives undertaken in order to capture a unique business opportunity (Miles, Paul & Wilhite, 2003). Nowadays, the vital role of corporate entrepreneurs during the process of CE is widely recognised (Zahra & Covin, 1995), and as a result entrepreneurial behaviours are promoted in organisations, as well (Antoncic & Hisrich, 2001; Hornsby, Kuratko & Zahra, 2002).

A corporate entrepreneur is an individual who has engaged in distinguished and remarkable enterprises, such as: improving the financial performance of an organisation, renovating activities, enhancing organisational change, taking risk, innovating throughout the organisation, acting competitively, recognising opportunities, chasing new products or markets (Zahra & Covin, 1995; Zahra, 1993), creating new businesses, reformulating strategies (Zahra, 1993) and strategic renewal (Dess & Lumpkin, 2005). The two main criteria for distinguishing corporate entrepreneurs are established entrepreneurial intention (EI), and entrepreneurial orientation (EO).

Entrepreneurial intention (EI)

The Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) defines EI as the percentage of individuals who expect to start businesses within the next three years (Amoros & Bosma, 2013). Douglas and Fitzsimmons (2013) argue that the EI of corporate entrepreneurs is to some extent different from other kinds. Accordingly, it would be more precise if the intentions of corporate entrepreneurs were separately investigated. It is notable that the self-reliance of corporate entrepreneurs also differs from that of other types of entrepreneurs. In this regard, corporate entrepreneurs are eager to accept direction and guidance from their superintendents, but SME entrepreneurs tend to be more self-reliant.

Entrepreneurial orientation (EO)

Many authors believe that EO has become a central concept in the domain of entrepreneurship. Thus, EO can be seen as a key issue for a firm’s success and as having a positive impact on the firm’s performance (Anderson & Eshima, 2013; Wang, 2008; Wiklund & Shepherd, 2003; 2005). Lumpkin and Dess (2001) define EO as the process of strategy-making. Anderson and Eshima (2013) refer to EO as a behavioural tendency and a strategic decision-making practice. Two fundamental dimensions that characterise EO are: i) aggressive behaviour toward competitors and ii) proactive responses to the marketplace (Zarei, Alambeigi, Zarei & Karimi, 2017).

Defining an entrepreneurial tournament

Since the main aim of the research is to formulate the rivalry process among corporate entrepreneurs by focusing on inter-organisational tournaments, it is necessary to have a clear image of an entrepreneurial tournament based on the literature. However, a complete definition of a “corporate entrepreneurial tournament” is one of the outputs of the research. Consequently, in this section, the nature of entrepreneurial competitions and entrepreneurial tournaments will be briefly discussed.

Entrepreneurial competitions

Haanes and Fjeldstad (2000) discuss three levels of resource competitions: i) entrepreneurial competition, ii) contractual-level competition and iii) operational competition. In the first level of competition some qualities are desirable and need to be acquired by entrepreneurs, for instance, know-how in basic technology, the ability to learn from ongoing projects, the ability and willingness to experiment and the ability to solve new problems and come up with innovative solutions. Schumpeter (1934) discusses the fact that entrepreneurial competitions combine resources in a new way. Kling (2010, p. 70) points out that the majority of economic progress comes from entrepreneurial competitions. Thus, entrepreneurial competitions are necessary for a dynamic and productive industry. Miles, Paul and Wilhite (2003), by debating Baumol’s (1990) idea of entrepreneurial competition, argue that the theory of entrepreneurial competition is fundamentally distinguished from the theory of price competition, since the output from an entrepreneurial competition is the introduction of a new product, process or organisational form – with the aim of enhancing the probability of creating and capturing value. In the entrepreneurship literature, competition refers to a contest among entrepreneurs; however, the notion of inter-organisational competition between corporate entrepreneurs has been neglected.

Entrepreneurial tournaments

There is no mature definition for the term “entrepreneurial tournament”. Nevertheless, the term has been partially quoted by a small number of authors during the past 20 years, (e.g., Christensen, Ulhoi & Madsen, 2000; Gattiker & Ulhoi, 2000; Kling, 2010; Low, Venkataraman & Srivatsan, 1994), though not in a systematic manner or with a specific intent. For instance, Low, Venkataraman and Srivatsan (1994) tried to enhance the classroom experience of entrepreneurship using solid theory. The research aimed to investigate the usefulness of an entrepreneurial game for both research and teaching. The authors found that similar opportunities are simultaneously identified by different entrepreneurs and, since one successful result tends to bring about another, so other entrepreneurs are deprived of access to resources. As a result, there is a continuous dynamic competition amongst entrepreneurs to increase revenue and obtain resources. In other words, entrepreneurship seems to be a continual competitive tournament. Gattiker and Ulhoi (2000) believe that an adequate network is a requirement for obtaining secure resources within an entrepreneurial tournament. Kling (2010, p. 69) argues that both power and wealth are involved in winner-takes-all tournaments, because, based on the theory, a small difference in performance results in a large difference in reward, especially within an ecosystem where there are few valuable positions and the best player achieves the most outstanding success.

Tournament theory

Since the aims of this study were initially established based on the principles of tournament theory, the theory is briefly presented here.

In tournament theory, the single criterion of the compensation principle – similar to operative performance – cannot by itself describe executives’ levels of pay. Describing this phenomenon was problematic for both classical and neoclassical economists. In fact, such strategic compensation behaviours derive from several paradigms and theories, for instance: marginal productivity theory, agency theory, human capital theory, institutional theory and, last but not least, tournament theory (Gomez-Mejia, Berrone & Franco-Santos, 2015, p. 120). Why a CEO is so highly paid in comparison with other employees was a question that attracted the attention of labour economists, and as a result, after some investigation, Lazear and Rosen (1981) introduced the concept of tournament theory. The theory presumes that an organisation’s employees, at the same rank, could be seen as rivals who compete with each other for promotion. The winner of the competition or tournament will perhaps be chosen as the next CEO of the organisation. Furthermore, the theory supposes that employees could be further motivated by greater rewards. Therefore, the organisation tries to create incentives (DeVaro, 2006). The winner of the tournament will be rewarded and her/his efforts during the tournament will be compensated, depending on the profit that she/he has generated for the organisation. Assigning a higher prize motivates employees to engage in the tournament more eagerly and to struggle more enthusiastically. In this regard, Eriksson (1999) submitted the theory to experimental testing by analysing 2,600 Danish executives. The research endorses the prediction of the theory in terms of the existence of a positive relationship between the tournament’s prize and the number of participants. Not always, but commonly, a very high reward is considered to be one of the main drivers of winning a tournament. However, the theory offers no further explanation of the rivalry process (Azevedo, Akdere & Larson, 2013), and this is the aspect that the current research tries to address by focusing on corporate entrepreneurs.

RESEARCH METHOD

The scope of the research was restricted to the individual level, and neither teams nor departments were considered. A qualitative methodology was chosen for addressing the aims of the research. In the current research, Strauss and Corbin’s (1990) version of grounded theory (GT) is used. During the 1960s Glaser and Strauss (1967) introduced the grounded theory methodology (GTM) as a response to the need for developing a systematic procedure for exploring phenomena in the domain of sociology. Urquhart and Fernández (2013) allude to different points of view adopted by Glaser (1992) and Strauss and Corbin (1990) concerning the coding paradigm and line-by-line coding procedures, which resulted in different versions of the method. The GTM examines individuals’ experiences and knowledge of a process with the aim of generating theory and providing a rational explanation of the process. The data in the GTM are commonly gathered by conducting interviews, via phone calls, online or face-to-face. The GTM is not commonly considered as a methodology for developing existing theories or opinions, due to the fact that the GTM tries to generate a novel theory from the grounded data. It is notable that in the current research, tournament theory has been used to develop hypotheses, not to form the theory. In addition, tournament theory offers no explanation at all for the rivalry process.

The GTM starts with asking broad-spectrum general queries of the statistical population, about the process that is being investigated. The statistical sample consists of individuals who have been recognised as appropriate for the aim of the research as they have experienced the processes and phenomena involved. The interviews are followed by open-ended questions and, based on the GTM approach, questioning should be continued until saturation is reached, e.g., a degree of knowledge about the phenomenon such that no new content or categories are generated by conducting more interviews (Bowen, 2008). Depending on the complexity of the process, saturation can be achieved at the 25th interview or thereafter. In the present study, theoretical saturation was achieved at the 32nd interview.

The content of the questions should be around the key issue and its related subjects. For instance, asking questions aimed at identifying the elements that have led to the emergence of the phenomenon – core phenomenon, investigating how and why the process is influenced – causal conditions, what actions have been taken by participants to deal with the situation – strategy, or even scrutinising the outcomes from implementing the strategies – consequences. The complete list of the categories that should be closely considered is known as the 6C coding family and/or the blocks of theory. These categories are presented as follows: i) causal conditions, ii) phenomenon, iii) context, iv) intervening conditions, v) strategies, and vi) consequences. In the next step, the gathered data are analysed through three rounds of coding: i) open coding, ii) axial coding and iii) selective coding.

During the research, when a new dimension of the phenomenon was revealed, the corporate entrepreneurs were sometimes interviewed more than twice. In this study, each entrepreneur was interviewed at least twice. These interviews were conducted over a five-month period using face-to-face interviews, phone calls and if necessary, emails. During the study period two research assistants facilitated the questioning procedure, which was also an efficient strategy for tackling possible biases. At the primary interviews and for the warm-up phase of the discussions, general questions were asked, such as: interviewees’ names, ages, positions, education, conducted strategies, detailed explanation of each tournament and so on. Semi-structured interviews were undertaken in accordance with Zorn (cited in Johnstone, 2007, p. 110). Each single interview lasted about 40-60 minutes. No specific software was used but all the interviews were recorded and then typed and dated in a booklet, labelled with each participant’s name. Eventually, the gathered data were entered into an Excel file to be later categorised based on the steps of the GTM.

Statistical population

For the aim of investigating and formulating the rivalry process between corporate entrepreneurs by using GTM, a corporation with some specific features should be investigated. Firstly, research on CE should be conducted within corporations, large firms or big business. Simply, a corporation can be defined as a legal entity that is officially registered by the government and includes groups of relationships and resources, with the main purpose of creating value for its stakeholders. However, in the context of CE, a corporation is defined as an organisation with more than 500 employees, although the number may change from country to county. Secondly, corporate entrepreneurs should be chosen who have experienced the rivalry process. In addition, they must be available to be interviewed during the various rounds of the GTM. After a series of close consultations with two associate professors of CE at the Faculty of Entrepreneurship, University of Tehran, it was decided that the research should be conducted at the Iran Telecommunication Research Center (ITRC). The centre is nationally known as one of the oldest, as well as the most up-to-date Iranian research institutions, established in 1970 through a treaty between the governments of Iran and Japan (“About ITRC”, 2017). The centre is among the main advisors of the Ministry of ICT in terms of ICT governance in the country. The majority of the centre’s duties are performed as research-based projects, and the centre has also launched several ICT-based products. The centre has more than 600 employees. Based on the employees’ capabilities, promotion can occur at any time, and guidelines for rewarding employees’ and for compensation are clear. These features are considered to be crucial for this research. Accordingly, two departments of the ITRC with a background of entrepreneurship and strategy were chosen: the Department of Business and Entrepreneurship and the Department of Strategy. Before conducting interviews, a sample consisting of 16 corporate entrepreneurs was identified, using the characteristics of corporate entrepreneurs described by Zahra and Covin (1995).

Table 1. Statistical population (list of interviewees)

|

Interviewees |

Educations |

Ages |

|

Senior Market Analyser |

M.Sc. of Industrial Engineering |

27 |

|

Chief Technology Researcher |

Ph.D. of Industrial Engineering |

32 |

|

Chief Information Technology Officer |

Ph.D. of Information Technology |

30 |

|

Business System Analyst |

M.Sc. of Economics |

32 |

|

Assistant HR Manager |

Ph.D. of Information Technology |

29 |

|

Attorney |

M.Sc. of Law |

28 |

|

Systems Analyst |

M.Sc. of Electronic |

28 |

|

Senior Security Specialist |

Ph.D. of Applied Mathematics |

32 |

|

Senior Network Engineer |

Ph.D. of Electronic |

28 |

|

Market Access Analyst |

Master of Business Administration |

43 |

|

Business Analyst |

Ph.D. of Economics |

27 |

|

Research and Development Associate |

M.Sc. of Management |

27 |

|

Research and Development Associate |

Ph.D. of Management |

28 |

|

Employee Relations Manager |

Ms. of Information Technology |

34 |

|

Senior Network Engineer |

Ph.D. of Wireless Communication |

32 |

|

Process Research Manager |

M.Sc. of Technology Management |

28 |

Of these, 19% were women and 81% men, and their educational levels could be categorised as PhD holders, MSc holders and others, at 50%, 44% and 6%, respectively.

Analysis (the coding paradigm of GTM)

Based on the GTM the data gathered from interviews should be analysed via three different rounds of coding. Corbin and Strauss (1990) introduced these levels of coding as: open coding, axial coding, and selective coding, and Charmaz (1990) named the whole process “theory generation”.

Open coding

As a rule, during open coding a bunch of text is encircled and then labelled. Following the procedures of GTM, the typed texts should be labelled sentence by sentence. In this research, open coding involved extracting 3416 labels, and 488 categories. In this level, the term “categories” refers to a combination of labels. This is demanding work but inspires the most original ideas. In addition, by using open coding, researchers are released from probable bias (Corbin & Strauss, 1990). Continuous comparative analysis should be performed in this level to ensure consistency in the data, and in the methods by which the data are categorised. For example, during open coding when new content is revealed which is not consistent with other categories, this may be an indication that it should be categorised under a new label.

When choosing the names of the labels and categorising them using an appropriate approach, the names of categories should make sense. Examples of categories used in this research are entrepreneurial intellectuality of experience, alertness and heuristics. For example, during the interviews a corporate entrepreneur argued that: “…by running my own business, co-operating with European researchers and working for several firms, I have learnt to take lessons from experiences and hence I do my best to make good use of those experiences, because I have nothing to lose…”.

In this regard, and in the context of entrepreneurship, Akanda (2015) refers to the above-mentioned quotation as “entrepreneurial intellectuality of experience”.

Alternatively, with regard to a Senior Market Analyser’s statement: “…you know, IoT and cloud [the terms referred to the Internet of Things and Cloud Computing] are being cited as breakthroughs in the world of ICT, I’ve never seen such a high potential tech [technology], it’s really fascinating, Gartner says [an international research company] around nine billion things [connected things such as smart phones with unique internet protocols] are going to be connected [to the web] by 2020, the agenda [The agenda for the connected world] is so close to happening, so this would be a big deal and I’m going to size them up even if it seems too far to achieve……by the way, I have a keen eye for such things…”, it is clear that this content refers to “alertness”.

After labelling a large quantity of raw qualitative data and by extracting reflective notes – memoing – the core categories should become apparent. In addition, by observing the memos, the researchers must think about the possible ways that these memos can explain the process under investigation. Finally, after reading the manuscripts from the interviews several times, the open coding is considered complete if there are no new categories.

Axial coding

The second round of the coding procedure is known as axial coding. In this level of coding the probable relationships among the categories which have emerged from the open coding are carefully considered. The main approach, for accomplishing axial coding, uses a paradigm known as the “coding paradigm”. The coding paradigm has various versions, but the current research follows Strauss and Corbin’s (1990) version. Based on this, the following terms are defined:

• Causal conditions: this refers to the factors that have influenced the central phenomenon, for instance, the triggers which have led to the emergence of an entrepreneurial tournament within an organization. The causal conditions are factors such as an efficient organisational reward system or the rewards given to the winners of tournaments.

• Phenomenon: this refers to the leading idea and the main process that the research aims to describe. This is the phenomenon which strategies have later been developed to deal with. In this case it will be the process by which a corporate entrepreneur has been successful in an entrepreneurial tournament.

• Context: this block alludes to the location of the event and its features such as the duration of the tournament or its participants.

• Action/interaction strategies: the perfect process requires implementation of a set of efficient strategies, which are utilised by corporate entrepreneurs, for instance, establishing an informal network or manipulating heuristic knowledge to win the tournament.

• Intervening conditions: Strauss and Corbin (1990) state that intervening conditions are commonly known as factors that have simplified or constrained the adopted strategies within the context, for instance cultural values or organisational life cycle.

• Consequences: consequences are outcomes of the applied strategies, for instance, achieving a legitimate power or an exceptional salary.

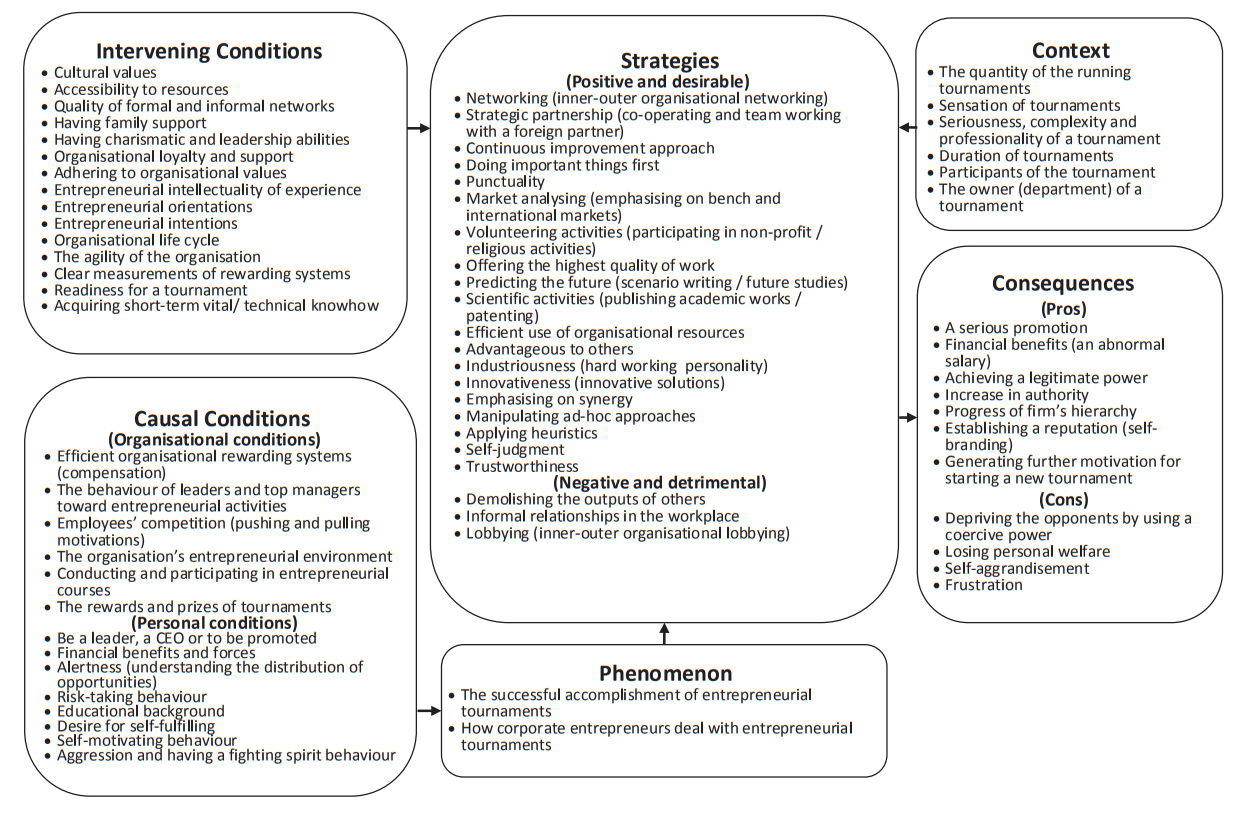

• Furthermore, the way the above-mentioned factors influence each other should be investigated. In this level, diagramming can be utilised as the best solution. Lines in the shape of arrows aid the researcher in deducing relationships. In fact, this method is suitable for explaining how the process works. The extracted model is presented in Figure 1.

Selective coding

At the final level of the GTM, all the categories should be unified around a central phenomenon that is known as the “core category”. The core category represents the central phenomenon of the study (Strauss & Corbin, 1990). Around the core category a storyline is developed, which is supported by strategies for accomplishing success in the tournament, and other blocks of theory. At this stage, there is no visualisation or diagramming, only a storyline. At the selective coding stage, the whole story together with the main storyline of the phenomenon should be developed, as an overall explanation of the generated theory. The storyline is a paragraph of interpretation about the generated theory that explains how the core process really functions. In this research, the core category is defined as “the successful accomplishment of entrepreneurial tournaments” and provides sufficient interpretation of how corporate entrepreneurs in an organisation have accomplished the process. The storyline is presented in the results section.

RESULTS

Based on the grounded data and on the rounds of coding, the generated theory of so-called “corporate entrepreneurial tournaments”, following the protocol of the storyline, is explained as follows:

A corporate entrepreneurial tournament is a dynamic rivalry process amongst corporate entrepreneurs in an organisation. Such tournaments are triggered by a combination of organisational and personal factors. The organisational factors are related to the motivational mechanisms of the organisation such as compensation and reward systems and the personal factors are based on the corporate entrepreneurs’ entrepreneurial behaviours. To achieve success in an entrepreneurial tournament, and to benefit from its rewards, is the leading motivation for entrepreneurs to participate in such tournaments. This achievement of success requires effective strategies. It does not matter if the adopted strategies are ipso facto detrimental or desirable; the strategies have only to be efficient. Furthermore, the adopted strategies are affected by the intervening conditions and by the context of each tournament. In this regard, the intervening conditions do not necessarily remain constant between each tournament, though they do not usually change during a given tournament. Examples of these conditions are cultural values, the agility of the organisation, the organisational life cycle and so on. In addition, the features of the context in which a tournament emerges affect the strategies, for instance the duration, participants and sensation of the tournament. Eventually, at the end of a corporate entrepreneurial tournament, there will be only one winner, who will be significantly rewarded. However, the consequences of winning a tournament are not always favourable. In fact, winning a corporate entrepreneurial tournament has its own advantages and disadvantages, for example: obtaining a significant promotion, a significant increase in salary or abusing the illegitimate power obtained.

The model extracted from the GTM depicting the details of the blocks of the theory is presented in Figure 1.

The reliability of the theory was considered in different ways. Firstly, the synthesised data was restricted to corporate entrepreneurs who have achieved success at least once in an entrepreneurial tournament. Secondly, to prevent bias, two research assistants were involved in the research, and both were completely aware of the theme of the research and the concepts of CE. Finally, those corporate entrepreneurs who participated in the research reviewed the generated model to see if it was consistent with the given statements.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

The grounded model developed in the research is to a great extent consistent with the literature of CE, for instance with McFadzean, O’Loughlin and Shaw’s (2005) model. However, these authors considered neither how the decision to act entrepreneurially is made, nor what strategies are used by corporate entrepreneurs to improve the performance of the corporation. The GTM model depicts that participating and accomplishing an entrepreneurial tournaments, entrepreneurial decisions, and applied strategies within entrepreneurial tournaments are highly affected by intervening and causal condition. This subject was not clearly investigated in previous CE models. In this regard, the model shows that to accelerate and facilitate entrepreneurial decisions, the managers can emphasise on providing better organisational conditions (e.g. establishing an efficient organisational rewarding system, holding entrepreneurial courses and so on), and personal conditions (e.g. alertness, risk-taking behaviour etc), despite the fact that some of the personal conditions like alertness cannot change, at least at the moment.

Alternatively, in Kuratko’s (2007) CE model the main categories of the model, from triggers to managerial outputs are considered, despite the fact that the author does not explain how corporate entrepreneurs have achieved these outcomes. In other words, a series of initiatives to win an entrepreneurial tournament is comprehensively illustrated by the model developed in this research, within the strategies block of the theory. The GTM model discloses not only these strategies, but also reveals that some of the applied strategies can be detrimental. For example, lobbying or establishing informal networks in the workplace to be informed of top managerial decisions sooner than other entrepreneurs, if the others do at all.

As tournament theory predicts, compensation mechanisms have always performed an important role in initiating any tournament. This notion is endorsed by the causal conditions of the grounded model. In this regard, Hayton and Kelley (2006) suggested a competency-based approach toward motivating CE instead of the traditional forms of job analyses. The GTM model goes further than the current boundaries and shows that not only organisational compensation mechanisms are crucial for a dynamic entrepreneurial tournament, but also allow entrepreneurs to follow tournaments more closely, especially when a notable reward or prize is set for each tournament.

Alertness or awareness of opportunities that other entrepreneurs are not fully aware of (Kirzner, 2017) has always appeared as an important factor in any entrepreneurial process. Its influence has been confirmed by this research, also. In fact, based on the conducted interviews, alertness as a way of understanding the distribution of opportunities and putting them into practice has been mentioned as a factor that can trigger corporate entrepreneurs to initiate a tournament. Risk-taking behaviours have constantly been cited as a determining factor for corporate entrepreneurial activities. With that in mind, Hayton (2005), in pursuit of a theoretical explanation for the effect of HRM in providing a better atmosphere for emerging CE, developed two interdependent themes: encouragement of discretionary entrepreneurial contributions and acceptance of risk. The model in this research shows that the risk-taking behaviour dimension is not only important, but also has an important role in initiating an entrepreneurial tournament.

Resources have frequently been mentioned as leading aspects of prosperous entrepreneurial activities (Burgelman, 1983; Khorrami, Zarei & Zarei, 2017; Wiklund & Shepherd, 2003). The outcomes of the research endorse this aspect also; for instance, the research shows that accessibility of resources is an intervening condition that determines the extent to which a corporate entrepreneur decides to initiate an entrepreneurial venture. Furthermore, efficient use of organisational resources is categorised as an efficient strategy, which is essential for a productive entrepreneurial tournament.

Networking is discussed as one of the main categories of intangible resources and the importance of such resources has been discussed using the resource-based view (RBV). However, few studies determine how exactly entrepreneurial networks function, especially within entrepreneurial tournaments. Apart from the research indorsing the importance of networking to entrepreneurs, which was recognised as an intervening condition, the GTM model finds out that the quality of networks, formal and informal, can be vital to entrepreneurs. In addition, the model depicts that networking can be applied by entrepreneurs as an efficient strategy to accomplish a successful tournament. Based on the interviews, networking has been used for sharing knowledge, reducing operating cost, accessing advanced technologies, recognising opportunities, evaluating entrepreneurial ideas, funding NSD and NPD projects and so on. As a result, the quality of entrepreneurial networks can define the intensity of entrepreneurial activities within a tournament.

Adhering to organisational values is crucial for corporate entrepreneurs (Burgelman, 1983), and in this regard, one of the main intervening conditions of the model was recognised as adhering to organisational values.

Nowadays, it is understood that CE is a process that engages more than one division of the organisation. As Burgelman (1983) argued: CE needs more than one participant because it is a multilayered activity. In this regard, the results of the research recognise networking, (both internal and external organisational networking), as a strategy that has apparently been adopted by corporate entrepreneurs.

Fostering entrepreneurial behaviours within an organisation is a crucial task when promoting entrepreneurship (Antoncic & Hisrich, 2001; Hornsby, Kuratko & Zahra, 2002), for instance by means of encouraging constructive contests, and it should therefore be addressed by managers. Consistently with this idea, employees’ competition as an organisational condition was recognised as an engine that encourages corporate entrepreneurs to initiate a tournament.

The research has also provided some managerial implications. One of the main concerns of HR managers should always be to motivate entrepreneurs to participate in tournaments, and not to quit their jobs. In fact, organisational desertion is a common phenomenon, especially for corporate entrepreneurs who are to some extent already mentally predisposed to quit the organisation and launch their own business start-up. In this research, entrepreneurial tournaments were discussed as an opportunity to tackle this problem.

As with any study, this research has some limitations. One basic limitation is related to the chosen methodology; it is common at the end of qualitative research for the theory to be examined with new data, to determine to what extent the theory remains consistent. In the current study, due to some limitations in the number of participants, “discriminant sampling” was ignored.

During the research, there was no emphasis on, or sensitivity to, ethnicity, gender or background ideologies such as religion, for which the reason behind this can be questionable.

Iran has some particular macroeconomic and social capital characteristics, such as the level of entrepreneurial activities and the current state of the economy, which have probably influenced the generality of the results.

Acknowledgments

Hereby I would like to acknowledge the help of the participants of the ITRC and the reviewers of the Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Innovation without whose insightful comments the research could not have been completed. In addition, I want to express my gratitude to those practitioners of Corporate Entrepreneurship (CE) who have opened ways to us to realise the value of CE.

References

- About ITRC. (2017, June). Retrieved from https://en.itrc.ac.ir/

- Akanda, A. (2015).Knowledge, Belief and Culture in Human Resource Management for HR Practitioners and Entrepreneurs. UK: Author House.

- Amoros, J. E., & Bosma, N. (2013). GEM Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, 2013 Global Report.Global Entrepreneurship Research Association (GERA).

- Anderson, B.S., & Eshima, Y. (2013). The influence of firm age and intangible resources on the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and firm growth among Japanese SMEs.Journal of Business Venturing, 28(3), 413-429.

- Antoncic, B., & Hisrich, R. D. (2001). Intrapreneurship: Construct refinement and cross-cultural validation. Journal of Business Venturing, 16(5), 495-527.

- Austin, J., Stevenson, H., & Wei-Skillern, J. (2006). Social and commercial entrepreneurship: Same, different, or both?.Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice,30(1), 1-22.

- Azevedo, R.E., Akdere, M., & Larson, E.C. (2013). Examining tournament theory in academe: Implications for the field of human resource development. Middle East Journal of Management, 1(1), 49-62.

- Barney, J.B. (2001). Is the resource-based “view” a useful perspective for strategic management research? Yes. Academy of Management Review, 26(1), 41-56.

- Baumol, W.J., 1990. Entrepreneurship: Productive, unproductive, and destructive. Journal of Political Economy, 98(5), 893–921.

- Bowen, G. A. (2008). Naturalistic inquiry and the saturation concept: A research note.Qualitative Research,8(1), 137-152.

- Burgelman, R.A. (1983). Corporate entrepreneurship and strategic management: Insights from a process study.Management Science,29(12), 1349-1364.

- Castrogiovanni, G.J., Urbano, D., & Loras, J. (2011). Linking corporate entrepreneurship and human resource management in SMEs. International Journal of Manpower, 32(1), 34-47.

- Chapman, C.A., & Valenta, K. (2015). Costs and benefits of group living are neither simple nor linear. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(48), 14751-14752.

- Charmaz, K. (1990). Discovering’chronic illness: Using grounded theory. Social Science & Medicine,30(11), 1161-1172.

- Christensen, P.V., Ulhoi, J.P., & Madsen, H. (2000). The entrepreneurial process in a dynamic network perspective: A review and future directions for research. Working paper, Aarhus School of Business, Aarhus BSS, Aarhus University, (last access 10 August 2016: http://www.forskningsdatabasen.dk/en/catalog/2194642601).

- Chu, W. (2009). The influence of family ownership on SME performance: Evidence from public firms in Taiwan.Small Business Economics,33(3), 353-373.

- Corbin, J.M., & Strauss, A. (1990). Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qualitative Sociology, 13(1), 3-21.

- Covin, J. G., & Miles, M. P. (1999). Corporate entrepreneurship and the pursuit of competitive advantage.Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice,23(3), 47-47.

- De Lurdes Calisto, M., & Sarkar, S. (2017). Organizations as biomes of entrepreneurial life: Towards a clarification of the corporate entrepreneurship process.Journal of Business Research,70, 44-54.

- Delfgaauw, J., Dur, R., Sol, J., & Verbeke, W. (2013). Tournament incentives in the field: Gender differences in the workplace. Journal of Labor Economics, 31(2), 305-326.

- Dess, Gregory G, & Lumpkin, G Tom. (2005). The role of entrepreneurial orientation in stimulating effective corporate entrepreneurship. The Academy of Management Executive, 19(1), 147-156.

- DeVaro, J. (2006). Strategic promotion tournaments and worker performance. Strategic Management Journal,27(8), 721-740.

- Dierickx, I., & Cool, K. (1989). Asset stock accumulation and sustainability of competitive advantage. Management Science, 35(12), 1504-1511.

- Douglas, E.J., & Fitzsimmons, J. R. (2013). Intrapreneurial intentions versus entrepreneurial intentions: Distinct constructs with different antecedents.Small Business Economics,41(1), 115-132.

- Eriksson, T. (1999). Executive compensation and tournament theory: Empirical tests on Danish data.Journal of labor Economics,17(2), 262-280.

- Gattiker, U. E., & Ulhoi, J. P. (2000). The entrepreneurial phenomena in a cross-national context.Handbook of Organizational Behaviour. 2nd ed. New York, USA: Marcel Dekker.

- Gill, D., & Prowse, V. (2014). Gender differences and dynamics in competition: The role of luck.Quantitative Economics,5(2), 351-376.

- Glaser, B.G. (1992). Emergence vs. Forcing: Basics of grounded theory analysis. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press.

- Glaser, B.G. & Strauss, A.L. (1967). The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for qualitative research. New York: Aldine Publishing Company.

- Gomez-Mejia, L. R., Berrone, P., & Franco-Santos, M. (2015).Compensation and organizational performance: Theory, research, and practice. USA: Routledge.

- Haan, T., Offerman, T., & Sloof, R. (2015). Discrimination in the Labour Market: The Curse of Competition between Workers.The Economic Journal, 127(603), 1433-1466.

- Haanes, K., & Fjeldstad, O. (2000). Linking intangible resources and competition.European Management Journal,18(1), 52-62.

- Hall, R. (1993). A framework linking intangible resources and capabilities to sustainable competitive advantage.Strategic Management Journal,14(8), 607-618.

- Hayton, J.C. (2005). Promoting corporate entrepreneurship through human resource management practices: A review of empirical research.Human Resource Management Review,15(1), 21-41.

- Hayton, J.C., & Kelley, D.J. (2006). A competency-based framework for promoting corporate entrepreneurship.Human Resource Management,45(3), 407-427.

- Hayton, J.C., & Kelley, D.J. (2006). A competency-based framework for promoting corporate entrepreneurship.Human Resource Management,45(3), 407-427.

- Hornsby, J.S., Kuratko, D.F., & Zahra, S.A. (2002). Middle managers’ perception of the internal environment for corporate entrepreneurship: Assessing a measurement scale.Journal of Business Venturing,17(3), 253-273.

- Ireland, R.D., & Webb, J.W. (2007). Strategic entrepreneurship: Creating competitive advantage through streams of innovation.Business Horizons,50(1), 49-59.

- Ireland, R.D., Covin, J.G., & Kuratko, D.F. (2009). Conceptualizing corporate entrepreneurship strategy.Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice,33(1), 19-46.

- Johnstone, B.A. (2007). Ethnographic methods in entrepreneurship research. In H. Neergaard & J.P. Ulhoi (Eds.) Handbook of qualitative research methods in entrepreneurship. UK: Edward Elgar, Cheltenham.

- Kearney, C., Hisrich, R., & Roche, F. (2007). Facilitating public sector corporate entrepreneurship process: A conceptual model.Journal of Enterprising Culture,15(03), 275-299.

- Khorrami, H., Zarei, M., & Zarei, B. (2017). Heuristics of the internationalisation of SMEs: A grounded theory method. International Journal of Management and Enterprise Development, 16(3), 174-206.

- Kirzner, I.M. (2017). The entrepreneurial market process—An exposition.Southern Economic Journal,83(4), 855-868.

- Kirzner, I.M. (1973). Competition and Entrepreneurship. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Kirzner, I.M. (1979). Perception, Opportunity and Profit: Studies in the Theory of Entrepreneurship. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Kirzner, I.M. (1992). The Meaning of Market Process. London: Routledge.

- Klein, P. G., & Bullock, J. B. (2006). Can entrepreneurship be taught?. Journal of Agricultural and Applied Economics, 38(2), 429-439.

- Kling, A.S. (2010).Unchecked and Unbalanced: How the Discrepancy Between Knowledge and Power Caused the Financial Crisis and Threatens Democracy. USA: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, INC.

- Knight, F.H. (1921). Risk, Uncertainty, and Profit. New York: August M. Kelley.

- Koenig, A. (2002). Competition for resources and its behavioral consequences among female primates. International Journal of Primatology, 23(4), 759-783.

- Kuratko, D.F. (2005). The emergence of entrepreneurship education: Development, trends, and challenges.Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29(5), 577-598.

- Kuratko, D.F. (2007). Corporate entrepreneurship.Foundations and Trends® in Entrepreneurship,3(2), 151-203.

- Kuratko, D.F., Hornsby, J. S., Naffziger, D. W., & Montagno, R. V. (1993). Implementing entrepreneurial thinking in established organizations.SAM Advanc ed Management Journal,58(1), 28.

- Lazear, E. & Rosen, S. (1981). Rank order tournaments as optimal labor contracts. Journal of Political Economy, 89(5), 841-864.

- Lazear, E. P. (1989). Pay equality and industrial politics.Journal of Political Economy, 97(3), 561-580.

- Linán, F., & Chen, Y. W. (2009). Development and cross-cultural application of a specific instrument to measure entrepreneurial intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice,33(3), 593-617.

- Low, M., Venkataraman, S., & Srivatsan, V. (1994). Developing an entrepreneurship game for teaching and research.Simulation & Gaming, 25(3), 383-401.

- Lumpkin, G. T., & Dess, G. G. (2001). Linking two dimensions of entrepreneurial orientation to firm performance: The moderating role of environment and industry life cycle.Journal of Business Venturing,16(5), 429-451.

- Mavi, R. K., Mavi, N. K., & Goh, M. (2017). Modeling corporate entrepreneurship success with ANFIS.Operational Research,17(1), 213-238.

- McDougall, P. P. (1989). International versus domestic entrepreneurship: new venture strategic behavior and industry structure.Journal of Business Venturing,4(6), 387-400.

- McFadzean, E., O’Loughlin, A., & Shaw, E. (2005). Corporate entrepreneurship and innovation, part 1: The missing link.European Journal of Innovation Management,8(3), 350-372.

- Miles, M. P., Paul, C. W., & Wilhite, A. (2003). Modeling corporate entrepreneurship as rent-seeking competition.Technovation,23(5), 393-400.

- Milinski, M., & Parker, G. A. (1991). Competition for resources. In J.R. Krebs & N.B. Davies (Eds.), Behavioural Ecology. An Evolutionary Approach (pp.137-168, 3rd ed.). Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications.

- Monk, R. (2000). Why small businesses fail: And what we can do about it. CMA Management 74(6), 12–13.

- Pearson, J., Pitfield, D., & Ryley, T. (2015). Intangible resources of competitive advantage: Analysis of 49 Asian airlines across three business models.Journal of Air Transport Management,47, 179-189.

- Petrick, J. A., Scherer, R. F., Brodzinski, J. D., Quinn, J. F., & Ainina, M. F. (1999). Global leadership skills and reputational capital: Intangible resources for sustainable competitive advantage.The Academy of Management Executive,13(1), 58-69.

- Prajogo, D. I., & Oke, A. (2016). Human capital, service innovation advantage, and business performance: The moderating roles of dynamic and competitive environments.International Journal of Operations & Production Management,36(9), 1-32.

- Purwaningsih, A. (2015). Analysis of customer mindset change and accounting practice of garbage bank as medium of edupreneurship. International Journal of Monetary Economics and Finance,8(4), 332-344.

- Rodrigues, L. R., Duncan, A. B., Clemente, S. H., Moya-Larano, J., & Magalhaes, S. (2016). Integrating Competition for Food, Hosts, or Mates via Experimental Evolution.Trends in Ecology & Evolution,31(2), 158-170.

- Schultz, T.W. (1975). The value of the ability to deal with disequilibria. Journal of Economic Literature, 13, 827-46.

- Schultz, T.W. (1979). Concepts of Entrepreneurship and Agricultural Research. USA: Kaldor Memorial Lecture, Iowa State University.

- Schultz, T.W. (1982). Investment in entrepreneurial ability. Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 82, 437-48.

- Schumpeter, J.A. (1934). The Theory of Economic Development: An Inquiry into Profits, Capital, Credit, Interest, and the Business Cycle. Cambridge, Mass. Harvard University Press.

- Sharma, P., & Chrisman, J. J. )1999(. Toward a reconciliation of the definitional issues in the field of corporate entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 23(3), 11-27.

- Shepherd, D. A., Covin, J. G., & Kuratko, D. F. (2009). Project failure from corporate entrepreneurship: Managing the grief process.Journal of Business Venturing,24(6), 588-600.

- Strauss, A.L. and Corbin, J.M. (1990). Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

- Takii, K. (2009). Entrepreneurial competition and its impact on the aggregate economy.Journal of Economics,97(1), 1-18.

- Teng, B.S. (2007). Corporate entrepreneurship activities through strategic alliances: A Resource-Based approach toward competitive advantage. Journal of Management Studies,44(1), 119-142.

- Urquhart, C., & Fernández, W. (2013). Using grounded theory method in information systems: The researcher as blank slate and other myths.Journal of Information Technology,28(3), 224-236.

- Van Ours, J. C., & Ridder, G. (1995). Job matching and job competition: Are lower educated workers at the back of job queues?.European Economic Review,39(9), 1717-1731.

- Wang, C. L. (2008). Entrepreneurial orientation, learning orientation, and firm performance.Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice,32(4), 635-657.

- Wiklund, J., & Shepherd, D. (2003). Knowledge-based resources, entrepreneurial orientation, and the performance of small and medium-sized businesses. Strategic Management Journal, 24(13), 1307-1314.

- Wiklund, J., & Shepherd, D. (2005). Entrepreneurial orientation and small business performance: A configurational approach.Journal of Business Venturing,20(1), 71-91.

- Zahra, S.A. (1991). Predictors and financial outcomes of corporate entrepreneurship: An exploratory study.Journal of Business Venturing,6(4), 259-285.

- Zahra, S.A. (1993). Environment, corporate entrepreneurship, and financial performance: A taxonomic approach.Journal of Business Venturing,8(4), 319-340.

- Zahra, S.A. (2015). Corporate entrepreneurship as knowledge creation and conversion: The role of entrepreneurial hubs.Small Business Economics,44(4), 727-735.

- Zahra, S.A., & Covin, J. G. (1995). Contextual influences on the corporate entrepreneurship-performance relationship: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Business Venturing,10(1), 43-58.

- Zarei, M., Alambeigi, A., Zarei, B., & Karimi, P. (2017). The effects of mergers and acquisitions (M&As) on bank performance and entrepreneurial orientation (EO). InS. Rezaei, L-P. Dana, & V. Ramadani (Eds.), Iranian Entrepreneurship. Deciphering the Entrepreneurial Ecosystem in Iran and in the Iranian Diaspora(pp. 361-375). Berlin: Springer International Publishing.

- Zarei, M., Jamalian, A., & Ghasemi, R. (2017). Industrial guidelines for stimulating entrepreneurship with the internet of things. InI. Lee (Ed.), The Internet of Things in the Modern Business Environment(pp. 147-166). USA: IGI Global.

- Zarei, M., Mohammadian, A., & Ghasemi, R. (2016). Internet of things in industries: A survey for sustainable development.International Journal of Innovation and Sustainable Development,10(4), 419-442.

- Zarei, M., Zarei, B., & Ghapanchi, A. H. (2017). Lessons learnt from process improvement in a non-profit organisation.International Journal of Business Excellence,11(3), 277-300.

- Zhou, C., & Peng, X. M. (2008). The entrepreneurial university in China: Nonlinear paths.Science and Public Policy 35 (9), 637-646.

Biographical note

Mohammad Zarei, has a M.Sc. in Corporate Entrepreneurship, has published several academic papers and book chapters with international publishers such as Springer, Inderscience and IGI Global and journals like International Journal of Management and Enterprise Development, International Journal of Innovation and Sustainable Development and International Journal of Business Excellence. He has six years’ experience in the third, governmental and private sectors, in organisational development and business process improvement. He has also participated in a number of national projects and achieved several letters of appreciation from the Iran Telecommunication Research Center (ITRC) and Ministry of ICT, Information Technology Organization of Iran. His research interests include strategies of corporate entrepreneurship (CE) and microeconomic studies.